[Originally posted at Huffington Post]

For the last 12 years, I’ve dedicated immense amounts of time, money, and energy to end violence against women and children. As a victim of violence myself, I’m deeply committed to destroying any institution or individual leveraging the sex-power matrix that results in child trafficking, nonconsensual prostitution, domestic violence, and other abuses. If I believed that censoring Craigslist would achieve these goals, I’d be the first in line to watch them fall. But from the bottom of my soul and the depths of my intellect, I believe that the current efforts to censor Craigslist’s “adult services” achieves the absolute opposite. Rather than helping those who are abused, it fundamentally helps pimps, human traffickers, and others who profit off of abusing others.

On Friday, under tremendous pressure from US Attorneys General and public advocacy groups, Craigslist shut down its “Adult Services” section. There is little doubt that this space has been used by people engaged in all sorts of illicit activities, many of which result in harmful abuses. But the debate that has ensued has centered on the wrong axis, pitting protecting the abused against freedom of speech. What’s implied in public discourse is that protecting potential victims requires censorship; thus, anti-censorship advocates are up in arms attacking regulators for trying to curtail first amendment rights. While I am certainly a proponent of free speech online, I find it utterly depressing that these groups fail to see how this is actually an issue of transparency, not free speech. And how this does more to hurt potential victims than help.

If you’ve ever met someone who is victimized through trafficking or prostitution, you’ll hear a pretty harrowing story about what it means to be invisible and powerless, feeling like no one cares and no one’s listening. Human trafficking and most forms of abusive prostitution exist in a black market, with corrupt intermediaries making connections and offering “protection” to those who they abuse for profit. The abused often have no recourse, either because their movements are heavily regulated (as with those trafficked) or because they’re violating the law themselves (as with prostitutes).

The Internet has changed the dynamics of prostitution and trafficking, making it easier for prostitutes and traffickers to connect with clients without too many layers of intermediaries. As a result, the Internet has become an intermediary, often without the knowledge of those internet service providers (ISPs) who are the conduits. This is what makes people believe that they should go after ISPs like Craigslist. Faulty logic suggests that if Craigslist is effectively a digital pimp whose profiting off of online traffic, why shouldn’t it be prosecuted as such?

The problem with this logic is that it fails to account for three important differences: 1) most ISPs have a fundamental business – if not moral – interest in helping protect people; 2) the visibility of illicit activities online makes it much easier to get at, and help, those who are being victimized; and 3) a one-stop-shop is more helpful for law enforcement than for criminals. In short, Craigslist is not a pimp, but a public perch from which law enforcement can watch without being seen.

#1: Internet Services Providers have a fundamental business interest in helping people.

When Internet companies profit off of online traffic, they need their clients to value them and the services they provide. If companies can’t be trusted – especially when money is exchanging hands – they lose business. This is especially true for companies that support peer-to-peer exchange of money and goods. This is what motivates services like eBay and Amazon to make it very easy for customers to get refunded when ripped off. Craigslist has made its name and business on helping people connect around services and while there are plenty of people who use its openness to try to abuse others, Craigslist is deeply committed to reducing fraud and abuse. It’s not always successful – no company is. And the more freedom that a company affords, the more room for abuse. But what makes Craigslist especially beloved is that is run by people who truly want to make the world a better place and who are deeply committed to a healthy civic life.

I have always been in awe of Craig Newmark, Craigslist’s founder and now a “customer service rep” with the company. He’s made a pretty penny off of Craigslist, so what’s he doing with it? Certainly not basking in the Caribbean sun. He’s dedicated his life to public service, working with organizations like Sunlight Foundation to increase government accountability and using his resources and networks to help out countless organizations like Donors Choose, Kiva, Consumer Reports, and Iraq/Afghani Vets of America. This is the villain behind Craigslist trying to pimp out abused people?

Craigslist is in a tremendous position to actually work _with_ law enforcement, both because it’s in their economic interests and because the people behind it genuinely want to do good in this world. This isn’t an organization dedicated to profiting off of criminals, hosting servers in corrupt political regimes to evade responsibility. This is an organization with both the incentives and interest to actually help. And they have a long track record of doing so.

#2: Visibility makes it easier to help victims.

If you live a privileged life, your exposure to prostitution may be limited to made-for-TV movies and a curious dip into the red light district of Amsterdam. You are most likely lucky enough to never have known someone who was forced into prostitution, let alone someone who was sold by or stolen from their parents as a child. Perhaps if you live in San Francisco or Las Vegas, you know a high-end escort who has freely chosen her life and works for an agency or lives in a community where she’s highly supported. Truly consensual prostitutes do exist, but the vast majority of prostitution is nonconsensual, either through force or desperation. And, no matter how many hip-hop songs try to imply otherwise, the vast majority of pimps are abusive, manipulative, corrupt, addicted bastards. To be fair, I will acknowledge that these scumbags are typically from abusive environments where they too are forced into their profession through circumstances that are unimaginable to most middle class folks. But I still don’t believe that this justifies their role in continuing the cycle of abuse.

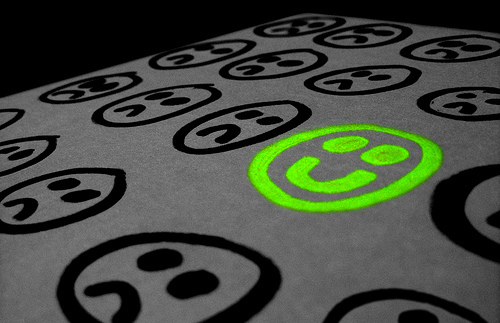

Along comes the Internet, exposing you to the underbelly of the economy, making visible the sex-power industry that makes you want to vomit. Most people see such cesspools online and imagine them to be the equivalent of a crack house opening up in their gated community. Let’s try a different metaphor. Why not think of it instead as a documentary movie happening real-time where you can actually do something about it?

Visibility is one of the trickiest issues in advocacy. Anyone who’s worked for a non-profit knows that getting people to care is really, really hard. Movies are made in the hopes that people will watch them and do something about the issues present. Protests and marathons are held in the hopes of bringing awareness to a topic. But there’s nothing like the awareness that can happen when it’s in your own backyard. And this is why advocates spend a lot of time trying to bring issues home to people.

Visibility serves many important purposes in advocacy. Not only does it motivate people to act, but it also shines a spotlight on every person involved in the issue at hand. In the case of nonconsensual prostitution and human trafficking, this means that those who are engaged in these activities aren’t so deeply underground as to be invisible. They’re right there. And while they feel protected by the theoretical power of anonymity and the belief that no one can physically approach and arrest them, they’re leaving traces of all sorts that make them far easier to find than most underground criminals.

#3: Law enforcement can make online spaces risky for criminals.

Law enforcement is always struggling to gain access to underground networks in order to go after the bastards who abuse people for profit. Underground enforcement is really difficult and it takes a lot of time to invade a community and build enough trust to get access to information that will hopefully lead to the dens of sin. While it always looks so easy on TV, there’s nothing easy or pretty about this kind of work. The Internet has given law enforcement more data than they even know what to do with, more information about more people engaged in more horrific abuses than they’ve ever been able to obtain through underground work. It’s far too easy to mistake more data for more crime and too many Aspiring Governors use the increase of data to spin the public into a frenzy about the dangers of the Internet. The increased availability of data is not the problem; it’s a godsend for getting at the root of the problem and actually helping people.

When law enforcement is ready to go after a criminal network, they systematically set up a sting, trying to get as many people as possible, knowing that whoever they have underground will immediately lose access the moment they act. The Internet changes this dynamic, because it’s a whole lot easier to be underground online, to invade networks and build trust, to go after people one at a time, to grab victims as they’re being victimized. It’s a lot easier to set up stings online, posing as buyers or sellers and luring scumbags into making the wrong move. All without compromising informants.

Working with ISPs to collect data and doing systematic online stings can make an online space more dangerous for criminals than for victims because this process erodes the trust in the intermediary, the online space. Eventually, law enforcement stings will make a space uninhabitable for criminals by making it too risky for them to try to operate there. Censoring a space may hurt the ISP but it does absolutely nothing to hurt the criminals. Making a space uninhabitable by making it risky for criminals to operate there – and publicizing it – is far more effective. This, by the way, is the core lesson that Giuliani’s crew learned in New York. The problem with this plan is that it requires funding law enforcement.

Using the Internet to combat the sex-power industry.

It makes me scream when I think of how many resources have been used attempting to censor Craigslist instead of leveraging it as a space for effective law enforcement. During the height of the moral panic over sexual predators on MySpace, I had the fortune of spending a lot of time with a few FBI folks and talking to a whole lot of local law enforcement. I learned a scary reality about criminal activity online. Folks in law enforcement know about a lot more criminal activity than they have the time to pursue. Sure, they focus on the Big players, going after the massive collectors of child pornography who are most likely to be sex offenders than spending time on the small-time abusers. But it was the medium-time criminals that gnawed at them. They were desperate for more resources so that they could train more law enforcers, pursue more cases, and help more victims. The Internet had made it a lot easier for them to find criminals, but that didn’t make their jobs any easier because they were now aware of how many more victims they were unable to help. Most law enforcement in this area are really there because they want to help people and it kills them when they can’t help everyone.

There’s a lot more political gain to be had demonizing profitable companies than demanding more money be spent (and thus, more taxes be raised) supporting the work that law enforcement does. Taking something that is visible and making it invisible makes a politician look good, even if it does absolutely nothing to help the victims who are harmed. It creates the illusion of safety, while signaling to pimps, traffickers, and other scumbags that their businesses are perfectly safe as long as they stay invisible. Sure, many of these scumbags have an incentive to be as visible as possible to reach as many possible clients as possible, and so they will move on and invade a new service where they can reach clients. And they’ll make that ISP’s life hell by putting them in the spotlight. And maybe they’ll choose an offshore one that American law enforcement can do nothing about. Censorship online is nothing more than whack-a-mole, pushing the issue elsewhere or more underground.

Censoring Craigslist will do absolutely nothing to help those being victimized, but it will do a lot to help those profiting off of victimization. Censoring Craigslist will also create new jobs for pimps and other corrupt intermediaries, since it’ll temporarily make it a whole lot harder for individual scumbags to find clients. This will be particularly devastating for the low-end prostitutes who were using Craigslist to escape violent pimps. Keep in mind that occasionally getting beaten up by a scary john is often a whole lot more desirable for many than the regular physical, psychological, and economic abuse they receive from their pimps. So while it’ll make it temporarily harder for clients to get access to abusive services, nothing good will come out of it in the long run.

If you want to end human trafficking, if you want to combat nonconsensual prostitution, if you care about the victims of the sex-power industry, don’t cheer Craigslist’s censorship. This did nothing to combat the cycle of abuse. What we desperately need are more resources for law enforcement to leverage the visibility of the Internet to go after the scumbags who abuse. What we desperately need are for sites like Craigslist to be encouraged to work with law enforcement and help create channels to actually help victims. What we need are innovative citizens who leverage new opportunities to devise new ways of countering abusive industries. We need to take this moment of visibility and embrace it, leverage it to create change, leverage it to help those who are victimized and lack the infrastructure to get help. What you see online should haunt you. But it should drive you to address the core problem by finding and helping victims, not looking for new ways to blindfold yourself. Please, I beg you, don’t close your eyes. We need you.

[As always, my views on my blog do not necessary reflect the opinons of any institution with which I’m affiliated. They are mine and mine alone.]