(This post was originally posted on Medium.)

For the second time in a week, my phone buzzed with a New York Times alert, notifying me that another celebrity had died by suicide. My heart sank. I tuned into the Crisis Text Line Slack channel to see how many people were waiting for a counselor’s help. Volunteer crisis counselors were pouring in, but the queue kept growing.

Celebrity suicides trigger people who are already on edge to wonder whether or not they too should seek death. Since the Werther effect study, in 1974, countless studies have conclusively and repeatedly shown that how the news media reports on suicide matters. The World Health Organization has adetailed set of recommendations for journalists and news media organizations on how to responsibly report on suicide so as to not trigger copycats. Yet in the past few years, few news organizations have bothered to abide by them, even as recent data shows that the reporting on Robin Williams’ death triggered an additional 10 percent increase in suicide and a 32 percent increase in people copying his method of death. The recommendations aren’t hard to follow — they focus on how to convey important information without adding to the problem.

Crisis counselors at the Crisis Text Line are on the front lines. As a board member, I’m in awe of their commitment and their willingness to help those who desperately need support and can’t find it anywhere else. But it pains me to watch as elite media amplifiers make counselors’ lives more difficult under the guise of reporting the news or entertaining the public.

Through data, we can see the pain triggered by 13 Reasons Why and the New York Times. We see how salacious reporting on method prompts people to consider that pathway of self-injury. Our volunteer counselors are desperately trying to keep people alive and get them help, while for-profit companies reap in dollars and clicks. If we’re lucky, the outlets triggering unstable people write off their guilt by providing a link to our services, with no consideration of how much pain they’ve caused or the costs we must endure.

I want to believe in journalism. But my faith is waning.

I want to believe in journalism. I want to believe in the idealized mandate of the fourth estate. I want to trust that editors and journalists are doing their best to responsibly inform the public and help create a more perfect union.But my faith is waning.

Many Americans — especially conservative Americans — do not trust contemporary news organizations. This “crisis” is well-trod territory, but the focus on fact-checking, media literacy, and business models tends to obscure three features of the contemporary information landscape that I think are poorly understood:

- Differences in worldview are being weaponized to polarize society.

- We cannot trust organizations, institutions, or professions when they’re abstracted away from us.

- Economic structures built on value extraction cannot enable healthy information ecosystems.

Let me begin by apologizing for the heady article, but the issues that we’re grappling with are too heady for a hot take. Please read this to challenge me, debate me, offer data to show that I’m wrong. I think we’ve got an ugly fight in front of us, and I think we need to get more sophisticated about our thinking, especially in a world where foreign policy is being boiled down to 140 characters.

1. Your Worldview Is Being Weaponized

I was a teenager when I showed up at a church wearing jeans and a T-shirt to see my friend perform in her choir. The pastor told me that I was not welcomebecause this was a house of God, and we must dress in a manner that honors Him. Not good at following rules, I responded flatly, “God made me naked. Should I strip now?” Needless to say, I did not get to see my friend sing.

Faith is an anchor for many people in the United States, but the norms that surround religious institutions are man-made, designed to help people make sense of the world in which we operate. Many religions encourage interrogation and questioning, but only within a well-established framework.Children learn those boundaries, just as they learn what is acceptable insecular society. They learn that talking about race is taboo and that questioning the existence of God may leave them ostracized.

Like many teenagers before and after me, I was obsessed with taboos and forbidden knowledge. I sought out the music Tipper Gore hated, read the books my school banned, and tried to get answers to any question that made adults gasp. Anonymously, I spent late nights engaged in conversations on Usenet, determined to push boundaries and make sense of adult hypocrisy.

Following a template learned in Model UN, I took on strong positions in order to debate and learn. Having already lost faith in the religious leaders in my community, I saw no reason to respect the dogma of any institution. And because I made a hobby out of proving teachers wrong, I had little patience for the so-called experts in my hometown. I was intellectually ravenous, but utterly impatient with, if not outright cruel to the adults around me. I rebelled against hierarchy and was determined to carve my own path at any cost.

I have an amazing amount of empathy for those who do not trust the institutions that elders have told them they must respect. Rage against the machine. We don’t need no education, no thought control. I’m also fully aware that you don’t garner trust in institutions through coercion or rational discussion. Instead, trust often emerges from extreme situations.

Many people have a moment where they wake up and feel like the world doesn’t really work like they once thought or like they were once told. That moment of cognitive reckoning is overwhelming. It can be triggered by any number of things — a breakup, a death, depression, a humiliating experience.Everything comes undone, and you feel like you’re in the middle of a tornado, unable to find the ground. This is the basis of countless literary classics, the crux of humanity. But it’s also a pivotal feature in how a society comes together to function.

Everyone needs solid ground, so that when your world has just been destabilized, what comes next matters. Who is the friend that picks you up and helps you put together the pieces? What institution — or its representatives — steps in to help you organize your thinking? What information do you grab onto in order to make sense of your experiences?

Contemporary propaganda isn’t about convincing someone to believe something, but convincing them to doubt what they think they know.

Countless organizations and movements exist to pick you up during your personal tornado and provide structure and a framework. Take a look at how Alcoholics Anonymous works. Other institutions and social bodies know how to trigger that instability and then help you find ground. Check out the dynamics underpinning military basic training. Organizations, movements, and institutions that can manipulate psychological tendencies toward a sociological end have significant power. Religious organizations, social movements, and educational institutions all play this role, whether or not they want to understand themselves as doing so.

Because there is power in defining a framework for people, there is good reason to be wary of any body that pulls people in when they are most vulnerable. Of course, that power is not inherently malevolent. There is fundamental goodness in providing structures to help those who are hurting make sense of the world around them. Where there be dragons is when these processes are weaponized, when these processes are designed to produce societal hatred alongside personal stability. After all, one of the fastest ways to bond people and help them find purpose is to offer up an enemy.

And here’s where we’re in a sticky spot right now. Many large institutions — government, the church, educational institutions, news organizations — are brazenly asserting their moral authority without grappling with their own shit.They’re ignoring those among them who are using hate as a tool, and they’re ignoring their own best practices and ethics, all to help feed a bottom line. Each of these institutions justifies itself by blaming someone or something to explain why they’re not actually that powerful, why they’re actually the victim. And so they’re all poised to be weaponized in a cultural war rooted in how we stabilize American insecurity.And if we’re completely honest with ourselves, what we’re really up against is how we collectively come to terms with a dying empire. But that’s a longer tangent.

Any teacher knows that it only takes a few students to completely disrupt a classroom. Forest fires spark easily under certain conditions, and the ripple effects are huge. As a child, when I raged against everyone and everything, it was my mother who held me into the night. When I was a teenager chatting my nights away on Usenet, the two people who most memorably picked me up and helped me find stable ground were a deployed soldier and a transgender woman, both of whom held me as I asked insane questions. They absorbed the impact and showed me a different way of thinking. They taught me the power of strangers counseling someone in crisis. As a college freshman, when I was spinning out of control, a computer science professor kept me solid and taught me how profoundly important a true mentor could be. Everyone needs someone to hold them when their world spins, whether that person be a friend, family, mentor, or stranger.

Fifteen years ago, when parents and the news media were panicking about online bullying, I saw a different risk. I saw countless kids crying out online in pain only to be ignored by those who preferred to prevent teachers from engaging with students online or to create laws punishing online bullies. We saw the suicides triggered as youth tried to make “It Gets Better” videos to find community, only to be further harassed at school. We saw teens studying the acts of Columbine shooters, seeking out community among those with hateful agendas and relishing the power of lashing out at those they perceived to be benefiting at their expense. But it all just seemed like a peculiar online phenomenon, proof that the internet was cruel. Too few of us tried to hold those youth who were unquestionably in pain.

Teens who are coming of age today are already ripe for instability. Their parents are stressed; even if they have jobs, nothing feels certain or stable. There doesn’t seem to be a path toward economic stability that doesn’t involve college, but there doesn’t seem to be a path toward college that doesn’t involve mind-bending debt. Opioids seem like a reasonable way to numb the pain in far too many communities. School doesn’t seem like a safe place, so teenagers look around and whisper among friends about who they believe to be the most likely shooter in their community. As Stephanie Georgopulos notes, the idea that any institution can offer security seems like a farce.

When I look around at who’s “holding” these youth, I can’t help but notice the presence of people with a hateful agenda. And they terrify me, in no small part because I remember an earlier incarnation.

In 1995, when I was trying to make sense of my sexuality, I turned to various online forums and asked a lot of idiotic questions. I was adopted by the aforementioned transgender woman and numerous other folks who heard me out, gave me pointers, and helped me think through what I felt. In 2001, when I tried to figure out what the next generation did, I realized thatstruggling youth were more likely to encounter a Christian gay “conversion therapy” group than a supportive queer peer. Queer folks were sick of being attacked by anti-LGBT groups, and so they had created safe spaces on private mailing lists that were hard for lost queer youth to find. And so it was that in their darkest hours, these youth were getting picked up by those with a hurtful agenda.

Teens who are trying to make sense of social issues aren’t finding progressive activists. They’re finding the so-called alt-right.

Fast-forward 15 years, and teens who are trying to make sense of social issues aren’t finding progressive activists willing to pick them up. They’re finding the so-called alt-right. I can’t tell you how many youth we’ve seen asking questions like I asked being rejected by people identifying with progressive social movements, only to find camaraderie among hate groups. What’s most striking is how many people with extreme ideas are willing to spend time engaging with folks who are in the tornado.

Spend time reading the comments below the YouTube videos of youth struggling to make sense of the world around them. You’ll quickly find comments by people who spend time in the manosphere or subscribe to white supremacist thinking. They are diving in and talking to these youth, offering a framework to make sense of the world, one rooted in deeply hateful ideas.These self-fashioned self-help actors are grooming people to see that their pain and confusion isn’t their fault, but the fault of feminists, immigrants, people of color. They’re helping them believe that the institutions they already distrust — the news media, Hollywood, government, school, even the church — are actually working to oppress them.

Most people who encounter these ideas won’t embrace them, but some will. Still, even those who don’t will never let go of the doubt that has been instilled in the institutions around them. It just takes a spark.

So how do we collectively make sense of the world around us? There isn’t one universal way of thinking, but even the act of constructing knowledge is becoming polarized. Responding to the uproar in the news media over “alternative facts,” Cory Doctorow noted:

We’re not living through a crisis about what is true, we’re living through a crisis about how we know whether something is true. We’re not disagreeing about facts, we’re disagreeing about epistemology. The “establishment” version of epistemology is, “We use evidence to arrive at the truth, vetted by independent verification (but trust us when we tell you that it’s all been independently verified by people who were properly skeptical and not the bosom buddies of the people they were supposed to be fact-checking).”

The “alternative facts” epistemological method goes like this: “The ‘independent’ experts who were supposed to be verifying the ‘evidence-based’ truth were actually in bed with the people they were supposed to be fact-checking. In the end, it’s all a matter of faith, then: you either have faith that ‘their’ experts are being truthful, or you have faith that we are. Ask your gut, what version feels more truthful?”

Doctorow creates these oppositional positions to make a point and to highlight that there is a war over epistemology, or the way in which we produce knowledge.

The reality is much messier, because what’s at stake isn’t simply about resolving two competing worldviews. Rather, what’s at stake is how there is no universal way of knowing, and we have reached a stage in our political climate where there is more power in seeding doubt, destabilizing knowledge, and encouraging others to distrust other systems of knowledge production.

Contemporary propaganda isn’t about convincing someone to believe something, but convincing them to doubt what they think they know. Andonce people’s assumptions have come undone, who is going to pick them up and help them create a coherent worldview?

2. You Can’t Trust Abstractions

Deeply committed to democratic governance, George Washington believed that a representative government could only work if the public knew their representatives. As a result, our Constitution states that each member of the House should represent no more than 30,000 constituents. When we stopped adding additional representatives to the House in 1913 (frozen at 435), each member represented roughly 225,000 constituents. Today, the ratio of congresspeople to constituents is more than 700,000:1. Most people will never meet their representative, and few feel as though Washington truly represents their interests. The democracy that we have is representational only in ideal, not in practice.

As our Founding Fathers knew, it’s hard to trust an institution when it feels inaccessible and abstract. All around us, institutions are increasingly divorced from the community in which they operate, with often devastating costs.Thanks to new models of law enforcement, police officers don’t typically come from the community they serve. In many poor communities, teachers also don’t come from the community in which they teach. The volunteer U.S. military hardly draws from all communities, and those who don’t know a solider are less likely to trust or respect the military.

Journalism can only function as the fourth estate when it serves as a tool to voice the concerns of the people and to inform those people of the issues that matter. Throughout the 20th century, communities of color challenged mainstream media’s limitations and highlighted that few newsrooms represented the diverse backgrounds of their audiences. As such, we saw the rise of ethnic media and a challenge to newsrooms to be smarter about their coverage. But let’s be real — even as news organizations articulate a commitment to the concerns of everyone, newsrooms have done a dreadful job of becoming more representative. Over the past decade, we’ve seen racial justice activists challenge newsrooms for their failure to cover Ferguson, Standing Rock, and other stories that affect communities of color.

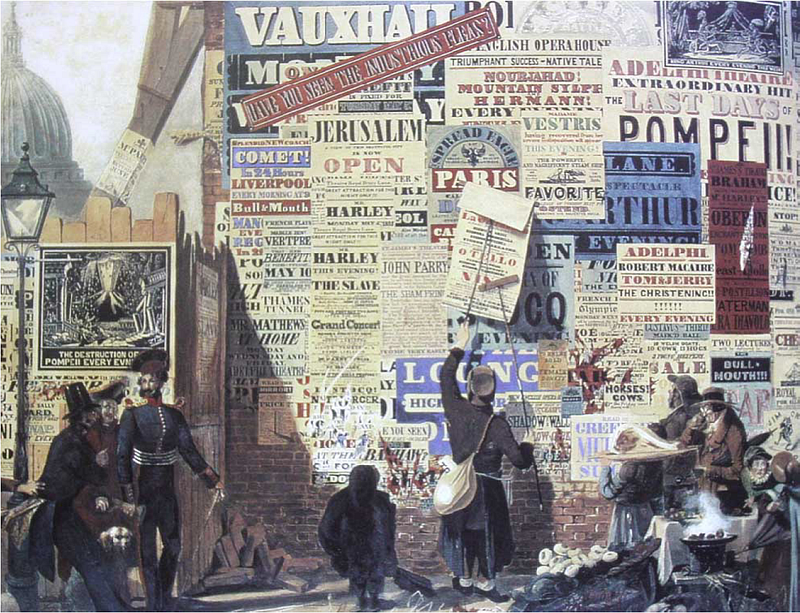

Meanwhile, local journalism has nearly died. The success of local journalismdidn’t just matter because those media outlets reported the news, but because it meant that many more people were likely to know journalists. It’s easier to trust an institution when it has a human face that you know and respect. Andas fewer and fewer people know journalists, they trust the institution less and less. Meanwhile, the rise of social media, blogging, and new forms of talk radio has meant that countless individuals have stepped in to cover issues not being covered by mainstream news, often using a style and voice that is quite unlike that deployed by mainstream news media.

We’ve also seen the rise of celebrity news hosts. These hosts help push the boundaries of parasocial interactions, allowing the audience to feel deep affinity toward these individuals, as though they are true friends. Tabloid papers have long capitalized on people’s desire to feel close to celebrities by helping people feel like they know the royal family or the Kardashians. Talking heads capitalize on this, in no small part by how they communicate with their audiences. So, when people watch Rachel Maddow or listen to Alex Jones, they feel more connected to the message than they would when reading a news article. They begin to trust these people as though they are neighbors. They feel real.

No amount of drop-in journalism will make up for the loss of journalists within the fabric of local communities.

People want to be informed, but who they trust to inform them is rooted in social networks, not institutions. The trust of institutions stems from trust in people. The loss of the local paper means a loss of trusted journalists and a connection to the practices of the newsroom. As always, people turn to their social networks to get information, but what flows through those social networks is less and less likely to be mainstream news. But here’s where you also get an epistemological divide.

As Francesca Tripodi points out, many conservative Christians have developed a media literacy practice that emphasizes the “original” text rather than an intermediary. Tripodi points out that the same type of scriptural inference that Christians apply in Bible study is often also applied to reading the Constitution, tax reform bills, and Google results. This approach is radically different than the approach others take when they rely on intermediaries to interpret news for them.

As the institutional construction of news media becomes more and more proximately divorced from the vast majority of people in the United States, we can and should expect trust in news to decline. No amount of fact-checking will make up for a widespread feeling that coverage is biased. No amount of articulated ethical commitments will make up for the feeling that you are being fed clickbait headlines.

No amount of drop-in journalism will make up for the loss of journalists within the fabric of local communities. And while the population who believes that CNN and the New York Times are “fake news” are not demographically representative, the questionable tactics that news organizations use are bound to increase distrust among those who still have faith in them.

3. The Fourth Estate and Financialization Are Incompatible

If you’re still with me at this point, you’re probably deeply invested in scholarship or journalism. And, unless you’re one of my friends, you’re probably bursting at the seams to tell me that the reason journalism is all screwed up is because the internet screwed news media’s business model. So I want to ask a favor: Quiet that voice in your head, take a deep breath, and let me offer an alternative perspective.

There are many types of capitalism. After all, the only thing that defines capitalism is the private control of industry (as opposed to government control). Most Americans have been socialized into believing that all forms of capitalism are inherently good (which, by the way, was a propaganda project). But few are encouraged to untangle the different types of capitalism and different dynamics that unfold depending on which structure is operating.

I grew up in mom-and-pop America, where many people dreamed of becoming small business owners. The model was simple: Go to the bank and get a loan to open a store or a company. Pay back that loan at a reasonable interest rate — knowing that the bank was making money — until eventually you owned the company outright. Build up assets, grow your company, and create something of value that you could pass on to your children.

In the 1980s, franchises became all the rage. Wannabe entrepreneurs saw a less risky path to owning their own business. Rather than having to figure it out alone, you could open a franchise with a known brand and a clear process for running the business. In return, you had to pay some overhead to the parent company. Sure, there were rules to follow and you could only buy supplies from known suppliers and you didn’t actually have full control, but it kinda felt like you did. Like being an Uber driver, it was the illusion of entrepreneurship that was so appealing. And most new franchise owners didn’t know any better, nor were they able to read the writing on the wall when the water all around them started boiling their froggy self. I watched my mother nearly drown, and the scars are still visible all over her body.

I will never forget the U.S. Savings & Loan crisis, not because I understood it, but because it was when I first realized that my Richard Scarry impression of how banks worked was way wrong. Only two decades later did I learn to seethe FIRE industries (Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate) as extractive ones.They aren’t there to help mom-and-pop companies build responsible businesses, but to extract value from their naiveté. Like today’s post-college youth are learning, loans aren’t there to help you be smart, but to bend your will.

It doesn’t take a quasi-documentary to realize thatMcDonald’s is not a fast-food franchise; it’s a real estate business that uses a franchise structure to extract capital from naive entrepreneurs. Go talk to a wannabe restaurant owner in New York City and ask them what it takes to start a business these days. You can’t even get a bank loan or lease in 2018 without significant investor backing, which means that the system isn’t set up for you to build a business and pay back the bank, pay a reasonable rent, and develop a valuable asset.You are simply a pawn in a financialized game between your investors, the real estate companies, the insurance companies, and the bank, all of which want to extract as much value from your effort as possible. You’re just another brick in the wall.

Now let’s look at the local news ecosystem. Starting in the 1980s, savvy investors realized that many local newspapers owned prime real estate in the center of key towns. These prized assets would make for great condos and office rentals. Throughout the country, local news shops started getting eaten up by private equity and hedge funds — or consolidated by organizations controlled by the same forces. Media conglomerates sold off their newsrooms as they felt increased pressure to increase profits quarter over quarter.

Building a sustainable news business was hard enough when the news had a wealthy patron who valued the goals of the enterprise. But the finance industry doesn’t care about sustaining the news business; it wants a return on investment. And the extractive financiers who targeted the news business weren’t looking to keep the news alive. They wanted to extract as much value from those business as possible. Taking a page out of McDonald’s, they forced the newsrooms to sell their real estate. Often, news organizations had to rent from new landlords who wanted obscene sums, often forcing them to move out of their buildings. News outlets were forced to reduce staff, reproduce more junk content, sell more ads, and find countless ways to cut costs. Of course the news suffered — the goal was to push news outlets into bankruptcy or sell, especially if the companies had pensions or other costs that couldn’t be excised.

Yes, the fragmentation of the advertising industry due to the internet hastened this process. And let’s also be clear that business models in the news business have never been clean. But no amount of innovative new business models will make up for the fact that you can’t sustain responsible journalism within a business structure that requires newsrooms to make more money quarter over quarter to appease investors. This does not mean that you can’t build a sustainable news business, but if the news is beholden to investors trying to extract value, it’s going to impossible. And if news companies have no assets to rely on (such as their now-sold real estate), they are fundamentally unstable and likely to engage in unhealthy business practices out of economic desperation.

Untangling our country from this current version of capitalism is going to be as difficult as curbing our addiction to fossil fuels. I’m not sure it can be done, but as long as we look at companies and blame their business models without looking at the infrastructure in which they are embedded, we won’t even begin taking the first steps. Fundamentally, both the New York Times and Facebook are public companies, beholden to investors and desperate to increase their market cap. Employees in both organizations believe themselves to be doing something important for society.

Of course, journalists don’t get paid well, while Facebook’s employees can easily threaten to walk out if the stock doesn’t keep rising, since they’re also investors. But we also need to recognize that the vast majority of Americans have a stake in the stock market. Pension plans, endowments, and retirement plans all depend on stocks going up — and those public companies depend on big investors investing in them. Financial managers don’t invest in news organizations that are happy to be stable break-even businesses. Heck, even Facebook is in deep trouble if it can’t continue to increase ROI, whether through attracting new customers (advertisers and users), increasing revenue per user, or diversifying its businesses. At some point, it too will get desperate, because no business can increase ROI forever.

ROI capitalism isn’t the only version of capitalism out there. We take it for granted and tacitly accept its weaknesses by creating binaries, as though the only alternative is Cold War Soviet Union–styled communism. We’re all frogs in an ocean that’s quickly getting warmer. Two degrees will affect a lot more than oceanfront properties.

Reclaiming Trust

In my mind, we have a hard road ahead of us if we actually want to rebuild trust in American society and its key institutions (which, TBH, I’m not sure is everyone’s goal). There are three key higher-order next steps, all of which are at the scale of the New Deal.

- Create a sustainable business structure for information intermediaries (like news organizations) that allows them to be profitable without the pressure of ROI. In the case of local journalism, this could involve subsidized rent, restrictions on types of investors or takeovers, or a smartly structured double bottom-line model. But the focus should be on strategically building news organizations as a national project to meet the needs of the fourth estate. It means moving away from a journalism model that is built on competition for scarce resources (ads, attention) to one that’s incentivized by societal benefits.

- Actively and strategically rebuild the social networks of America.Create programs beyond the military that incentivize people from different walks of life to come together and achieve something great for this country. This could be connected to job training programs or rooted in community service, but it cannot be done through the government alone or, perhaps, at all. We need the private sector, religious organizations, and educational institutions to come together and commit to designing programs that knit together America while also providing the tools of opportunity.

- Find new ways of holding those who are struggling. We don’t have a social safety net in America. For many, the church provides the only accessible net when folks are lost and struggling, but we need a lot more.We need to work together to build networks that can catch people when they’re falling. We’ve relied on volunteer labor for a long time in this domain—women, churches, volunteer civic organizations—but our current social configuration makes this extraordinarily difficult. We’re in the middle of an opiate crisis for a reason. We need to think smartly about how these structures or networks can be built and sustained so that we can collectively reach out to those who are falling through the cracks.

Fundamentally, we need to stop triggering one another because we’re facing our own perceived pain. This means we need to build large-scale cultural resilience. While we may be teaching our children “social-emotional learning”in the classroom, we also need to start taking responsibility at scale.Individually, we need to step back and empathize with others’ worldviews and reach out to support those who are struggling. But our institutions also have important work to do.

At the end of the day, if journalistic ethics means anything, newsrooms cannot justify creating spectacle out of their reporting on suicide or other topics just because they feel pressure to create clicks. They have the privilege of choosing what to amplify, and they should focus on what is beneficial. If they can’t operate by those values, they don’t deserve our trust. While I strongly believe that technology companies have a lot of important work to do to be socially beneficial, I hold news organizations to a higher standard because of their own articulated commitments and expectations that they serve as the fourth estate. And if they can’t operationalize ethical practices, I fear the society that must be knitted together to self-govern is bound to fragment even further.

Trust cannot be demanded. It’s only earned by being there at critical junctures when people are in crisis and need help. You don’t earn trust when things are going well; you earn trust by being a rock during a tornado. The winds are blowing really hard right now. Look around. Who is helping us find solid ground?