For the last year, I’ve been trying to get my head around different aspects of human trafficking and the commercial sexual exploitation of minors. I’ve been meeting with a variety of relevant actors, including anti-trafficking advocates, law enforcement officers, researchers, and sex workers. I’ve talked with survivors and buyers, observed online traces, and scoured the literature. Throughout all of this, I’ve developed a very uneasy feeling about the way language is leveraged in this domain. In particular, I’m deeply bothered by the ways in which the concept of “trafficking” is employed by different groups in ways that confuse and obfuscate different aspects of commercial sex. There is no doubt that the politics around sex work and trafficking are ugly, but if we’re actually going to help those who are abused and exploited, we need to get beyond coarse categories and try to understand the messiness.

For the last year, I’ve been trying to get my head around different aspects of human trafficking and the commercial sexual exploitation of minors. I’ve been meeting with a variety of relevant actors, including anti-trafficking advocates, law enforcement officers, researchers, and sex workers. I’ve talked with survivors and buyers, observed online traces, and scoured the literature. Throughout all of this, I’ve developed a very uneasy feeling about the way language is leveraged in this domain. In particular, I’m deeply bothered by the ways in which the concept of “trafficking” is employed by different groups in ways that confuse and obfuscate different aspects of commercial sex. There is no doubt that the politics around sex work and trafficking are ugly, but if we’re actually going to help those who are abused and exploited, we need to get beyond coarse categories and try to understand the messiness.

As I’ve grappled with my own conceptualization of the issues in this space, I’ve come to realize that those invested in anti-trafficking interventions would gain a lot from talking with – and, more importantly, listening to – sex workers. (See: Sex Workers Project to learn more.) I know that’s controversial, but let me offer some of what I’ve learned by talking with those who identify as sex workers and why I believe that this divide must be bridged.

The Language of Choice, Circumstance, and Coercion

Commercial sex is not a homogenous practice. In talking with various sex workers and sex-positive activists, I often hear the language of “choice, circumstance, or coercion” employed. Although I’ve heard a variety of different definitions, I’ve come to understand this language as a spectrum. On one end, you have choice where individuals with a high level of agency and capital (social, economic, cultural) choose to engage in sex work, often because they hold pro-sex attitudes and believe that the world would be a better place if people were more open and honest sexually. Terms employed by these sex workers (and their clients) include “sex workers,” “escorts” and “high end prostitutes”; those who identify as such are often engaged in pro-sex public narratives. On the other end of the spectrum, you have coercion where individuals lack any form agency or capital and are directly or indirectly forced into the trade through manipulation or force. In between, in a category that describes what I suspect is the bulk of commercial sex, is circumstance. Circumstance itself can also be treated as a spectrum. On the end closest to choice, you have individuals who believe that they should have the right to sell any part of their bodies for financial gain. The logic is simple: why should one’s genitals be off-limits when one is allowed to sell one’s brains, hands, or back for labor? The bulk of circumstance has more to do with challenging economic issues, including poverty or financial desperation. Finally, closest to coercion, there are individuals who are both financially hard off as well as grappling with serious mental health issues, including drug and alcohol addiction, gender dysphoria, a history of abuse, and/or co-dependency.

Many anti-trafficking advocates, including second wave feminists and religious individuals view all forms of commercial sex as being coercive in nature. Many who cite religious beliefs in condemning prostitution focus on the issue of morality, either drawing on texts that condemn prostitution or arguing that people who engage in such sinful acts must not be in their right mind. Feminists who are opposed to all forms of sex work highlight that the structural conditions of oppression – including a long history of sexism, racism, homophobia, and classism – make it impossible for low-status individuals to freely choose to consent to sex for money.

The language of choice, circumstance, and coercion can get murky for precisely the reasons the feminists highlight. Plenty of oppressed individuals believe that they are engaged in sex work by choice, even when they’re grappling with mental illness and abuse. And the history of inequality and structural oppression means that many low-status individuals see few opportunities beyond commercial sex to make ends meet.

While this framework – choice, circumstance, and coercion – is primarily used to describe adult sex work, talking about youth is more complicated. On one hand, it makes sense to talk about youth as coerced, regardless of how they see themselves, for teenagers definitely lack legal agency, typically lack social agency, and are often unaware of how their circumstances create conditions in which they cannot consent to trading sex for money. Yet, in talking with teenagers – especially those who do not work for a pimp – it’s clear that many see themselves as making a choice that’s predicated on circumstances. Some – but not all – teens see commercial sex as a mechanism by which they can achieve financial independence in light of existing oppression.

As I struggle to make sense of how to understand teens’ self-perception, I started to realize that addressing the intwined issues involved in trafficking requires starting with where people are at, regardless of how we feel about their own self-perceptions. In other words, rather than externally evaluating where someone is on the choice, circumstance, and coercion spectrum, it’s important to begin by asking them where they see themselves to be. Why? This spectrum of commercial sex doesn’t just provide a roadmap for understanding how people perceive their own practice, but it also provides a framework for thinking about interventions.

Intervening: The Value of Choice, Circumstance, and Coercion as a Model

In order for an anti-trafficking intervention to work, it needs to be situated in context. All too often, we hear about cases of foreigners who are trafficked for sexual purposes, “rescued” and repatriated, only to be once again trafficked. Upon investigation, these cases almost always turn out to be driven by circumstance. For some, the financial gain of being in the life outweighs the abuse that it entails. This is horrible, but ignoring this does little to combat it.

Regardless of how someone feels about sex work, treating all commercial sex as coercive does little to address the underlying structural and social conditions that produce it. By focusing on how someone sees themselves across the spectrum, it’s easier to start imagining different kinds of interventions. For example, if someone has the social, economic, and cultural capital to make a choice to engage in sex work, the intervention that’s needed is very different than what’s needed to help someone who lacks these capacities.

There is no doubt that legal interventions are needed to get at the heart of coercion and the resultant trafficking that occurs. Unfortunately, this is where it becomes clear how broken our legal structures are. In far too many states, those who have been forced into commercial sex are the ones who are prosecuted when they get caught. And those who exploit these people – either by buying or selling them – are rarely prosecuted. This creates a situation where those who are coerced can barely tell the difference between their abuser and the State. From their perspective, at least their abuser offers love and support alongside the abuse. If we want to make a difference in the lives of those who are coerced into commercial sex, we need to make certain that they are supported, not punished. And we need to make sure that exploitation is one of the riskiest things that people can do.

Yet, as we move across the spectrum towards circumstance, it becomes clear that our lack of social services is haunting us. Far too few people have access to mental health services, let alone have the support structures to address the demons that haunt them. Foster care is fundamentally broken, the cost of mental health care is inaccessible for many, and there is very little in the way of social services for those who are struggling. People slip through the cracks all over the place. It’s no wonder that most youth who get into the life are “runaways” or “throwaways.”

If we want to make a difference here, we need to construct social services that can truly help those most at-risk, long before they end up in the life. Once they’re there, they need social services even more, regardless of whether they see themselves as trafficked or simply engaging in circumstantial-based sex work. We can’t expect those who are dealing with serious mental health issues to magically be OK once they’ve been identified. Yet, in far too many environments, that’s exactly what we expect. Given this, it’s no wonder that abused individuals keep returning to commercial sex, long after they’re adults.

Moving out of the realm of direct abuse, there are other serious components to circumstance. I do not believe that we can address the issue of sex work by circumstance without seriously reflecting on the economic state of our society. When people have limited economic choices, they often make difficult trade-offs. And when faced with a stark reality of minimum wage labor that doesn’t pay a living wage, countless individuals seek alternative financial opportunities, including selling parts of themselves that they would prefer not to. I will never forget talking with a teen who turned to sex work because she could figure out no other mechanism to help support her injured undocumented mother and younger siblings. From my perspective, sex work by circumstance is all too often a by-product of deeply flawed economic policies. We cannot expect to prosecute our way out of this. Most adults that I’ve met who engage in sex work by circumstance understand the risks and have made a hard and troublesome calculation that the risk outweighs the alternatives. Most youth feel as though they have no other option. The cost of poverty runs deep in our country, especially for children who lack parental support and women of color.

I’m not saying that the practices of those who exploit children or adults who enter into the life out of circumstance can or should be justified, but I think that it’s important to recognize that not all exploitative sex work takes the form of an abusive pimp engaged in physical oppression. Far too often, the exploitation that is occurring is a result of social and structural conditions that we’ve created as a society. Collapsing choice, circumstance, and coercion into one category of sex work or trafficking erodes the nuances that explain people’s engagement with sex for money and obfuscates the dynamics that configure people’s practices. If we want to intervene in a meaningful way, we need to draw out these nuances and build a more complex intervention model.

Exploitation and Violence

Nearly everyone is comfortable condemning the violence that occurs when people are explicitly, directly, and coercively forced into being exploited. The common presence of violence and abuse is part of why those who are opposed to all forms of sex work conceptualize it all as trafficking. Yet, it’s important to untangle the ways in which violence operate in sex work and exploitation. Some sex workers are never violated or victimized, but, sadly, violence is all too common. This does not mean that it’s acceptable. Regardless of how someone perceives their engagement with sex work, it is never acceptable for them to be violated, abused, or raped. Period. And we need to make sure that those who are are supported and helped. I get furious what I hear people shrug off rapes of sex workers with comments like “well, it’s her job, she deserved it.” No one deserves to get raped or to have sex against their consent, regardless of whether or not they choose to engage in sex work.

But in some ways, that’s the easiest side of violence surrounding sex work and exploitation. When people are accustomed to being abused, they stop seeing it as abuse. One of the heart-wrenching aspects of the commercial sexual exploitation of minors is that many of them were violated long before they entered into the life. It is all too common to hear stories of rape by family members – father, uncles, brothers, cousins – that predate their commercial sexual exploitation. What kills me is hearing stories about how much “nicer” their commercial exploiters are than their own family.

It is important to recognize the ways in which violence and abuse operates around and within the contexts of commercial sexual exploitation – and the role that it plays in shaping people’s decisions to get involved in sex work. It still boggles my mind that we do so little in this country to address familial abuse and then are surprised when it results in seriously problematic dynamics. If we want to curb commercial sexual exploitation, we need to counter all forms of sexual exploitation.

What Sex Workers See

I’ve never spoken with a radical, pro-sex sex worker who’s not absolutely horrified by commercial sexual exploitation. Even those who are pushing for legalization of prostitution are outraged that people are being exploited for commercial gain. May who identify as sex workers actively work to combat trafficking. It’s not like those who believe in sex work believe in rape. These are fundamentally different things.

Folks in the anti-trafficking worlds need to recognize how valuable sex workers can be as allies. Regardless of how any anti-trafficking group may feel about sex workers, one thing is clear: sex workers often have more access into the worlds in which the majority of commercial sexual exploitation takes place. This access can be leveraged to find victimized youth, to help do interventions, and to identify exploiters.

What sex workers see can be of great value to combating sexual exploitation, but leveraging this knowledge requires collaborations between unlikely parties. My hope is that anti-trafficking advocates and sex workers can find ways to work together to combat commercial sexual exploitation. They have a lot to learn from one another about the complexities of the issue. When it comes to sexual exploitation, pro-sex advocates are not at odds with anti-trafficking organizations. They may see the world from a different perspective, but both groups want to end exploitation.

Of course, this all presupposes that the goal is to actually combat commercial sexual exploitation, change structural conditions to minimize oppression, and otherwise address the crux of the issue. Which, I admit, is a bit optimistic given the highly political nature of all of this.

But to the degree that the disagreement comes down to ideology and framing, I think that a lot could be gained from making a concerted effort to find common ground and to hear why each group is using the language and models that they are to make sense of the nuanced experiences and situations that they’re encountering. At the end of the day, I hope that we can agree to help address the structural and social conditions that shape desperation, abuse, and exploitation. In order to make a difference, we need to not get caught up in political and ideological battles, but work to develop a nuanced understanding of the ecosystem. This means taking a multi-prompted, complex systems approach to understanding what’s happening and why. And it means building connections and listening to voices that approach the issue from a different perspective.

As more and more organizations get involved in anti-trafficking advocacy, I really hope that folks will take a moment to listen to and learn from those who identify as sex workers. The language and frames that they use may seem foreign, but I would argue that they’re quite helpful in getting at different aspects of the issue. And we really need to be building large networks of allies committed to combating exploitation if we’re going to make a difference in this complex problem.

(I am deeply indebted to Melissa Gira Grant for pushing me to think critically about these issues. For those interested in learning more about the politics and legal issues surrounding sex work, I recommend reaching out to her. And I’m also thankful to Jennifer Musto of Rice University for helping me understand the framing debates.)

This post was also posted elsewhere. Follow these links to see related conversations:

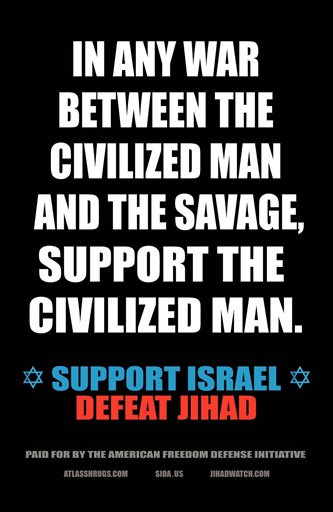

Meanwhile, in the United States, a lawsuit was moving through the courts concerning a deeply racist advertisement that “The American Freedom Defense Initiative” wanted to pay to have displayed by New York City’s subway system (MTA). The MTA went to the courts in an effort to block the advertisement which implicitly linked Muslims to savages. The MTA lost their court battle when a judge argued that this racist ad was protected speech, thereby forcing the MTA to accept and post the advertisements. Begrudgingly, they did. And this is where we get to Mona.

Meanwhile, in the United States, a lawsuit was moving through the courts concerning a deeply racist advertisement that “The American Freedom Defense Initiative” wanted to pay to have displayed by New York City’s subway system (MTA). The MTA went to the courts in an effort to block the advertisement which implicitly linked Muslims to savages. The MTA lost their court battle when a judge argued that this racist ad was protected speech, thereby forcing the MTA to accept and post the advertisements. Begrudgingly, they did. And this is where we get to Mona.