On Tuesday, Egyptian-American activist Mona Eltahawy was arrested for “criminal mischief” – or “the willful damaging of property” – when she responded to disturbingly racist ads that were posted in the New York City subway system with spray paint. Her act of political resistance went beyond spray paint however. In some ways, it was intentionally designed to get the attention of the internet. When she encountered resistance from a person defending the ads – who clearly knew Mona and kept responding to her by name – Eltahawy chose to create a challenge over her right to engage in what she called “freedom of expression.” This altercation escalates as the two argue on camera over whether or not Eltahawy is violating free speech or “making an expression on free speech.” (The video can be seen here.) As this encounter unfolds, Eltahawy regularly turns to the video and speaks to “the internet,” indicating that she knew full well that this video would be made available online. In constructing her audience, Eltahawy also switches between talking to Americans (“see this America”) and to a broader international public, presumably of people who are angry at the perceived hypocrisy of how America constructs free speech in light of the video mocking Islam’s prophet that sparked riots around the globe.

On Tuesday, Egyptian-American activist Mona Eltahawy was arrested for “criminal mischief” – or “the willful damaging of property” – when she responded to disturbingly racist ads that were posted in the New York City subway system with spray paint. Her act of political resistance went beyond spray paint however. In some ways, it was intentionally designed to get the attention of the internet. When she encountered resistance from a person defending the ads – who clearly knew Mona and kept responding to her by name – Eltahawy chose to create a challenge over her right to engage in what she called “freedom of expression.” This altercation escalates as the two argue on camera over whether or not Eltahawy is violating free speech or “making an expression on free speech.” (The video can be seen here.) As this encounter unfolds, Eltahawy regularly turns to the video and speaks to “the internet,” indicating that she knew full well that this video would be made available online. In constructing her audience, Eltahawy also switches between talking to Americans (“see this America”) and to a broader international public, presumably of people who are angry at the perceived hypocrisy of how America constructs free speech in light of the video mocking Islam’s prophet that sparked riots around the globe.

As I watch this video and try to untangle the dynamics going on, I can’t help but reflect on the cultural collision course underway as the notion of “free speech” gets decontextualized in light of heightened visibility. But before I get there, I need to offer some more context.

Free Speech in the United States

In the United States, the First Amendment to the Constitution states: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” This is the foundation of the “free speech” clause that is one of the most unique aspects of American political life. It means that people have the right to speak their mind, even if their speech is unpopular, blasphemous, or critical.

Over the last 200+ years, there have been interesting cases that pit free speech against other issues that result in what may be perceived to be special carve-outs. For example, “hate speech” is not protected under civil rights clauses when it constitutes a form of harassment. Child pornography is not considered free speech but, rather, photographic evidence of a crime against a child. And speech that incites violence is not considered free speech if it serves to create an imminent threat of violence. (Of course, the edge cases on this are often dicey.) But content that depicts many things that are deemed offensive – including grotesque imagery, obscene pornography, and extreme violence – is often protected by free speech, even if public display of it is limited.

Of course, what taketh also giveth. Many European countries have begun banning women from wearing the hijab, seeing it as an oppressive dress. In the United States, the same first amendment that permits racist and blasphemous content also protects Muslim women in their choice of clothing. Even when people are racist shits, Muslims have a tremendous amount of freedom afforded to them because of US laws that forbid discrimination on the basis of religion. Does that make it easy to be Muslim in the US? No. But being Muslim in the US is a hell of a lot more protected than being Jewish in any Arab state.

As offensive (and, frankly, dreadfully awful) as the pseudo-pornographic film “Innocence of Muslims” is, it’s protected under free speech in the United States. This is not the first film to depict religious figures in problematic ways, nor will it be the last. As The Onion satirically reminds us, there are plenty of sexualized images out there depicting religious figures in all sorts of upsetting ways.

Yet, this video spread far beyond the walls of the United States, into other regions where the very notion of “free speech” is absent. Many Muslims were outraged at the idea that their prophet might be depicted in such an offensive manner and some took to the streets in anger. Some interpreted the video as hateful and couldn’t understand why such content would ever be allowed. Meanwhile, many Americans failed to understand why such a video would be uniquely provocative in Muslim communities. On more than one occasion, I heard Americans ask questions like: Why should it be illegal to represent a religious figure in a negative light when it’s so common in Muslim societies to be so hateful to people of other religions? Or to be hateful towards women or LGBT people? Or to depict women in negative ways? Needless to say, all of this rests on a fundamental moral disconnect around what values can and should shape a society.

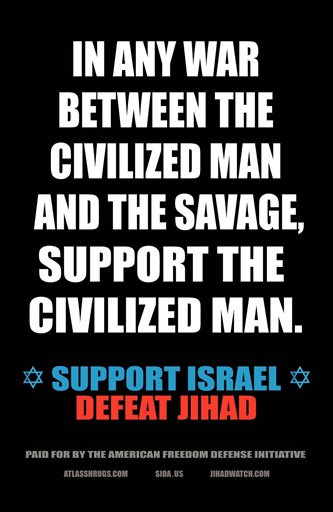

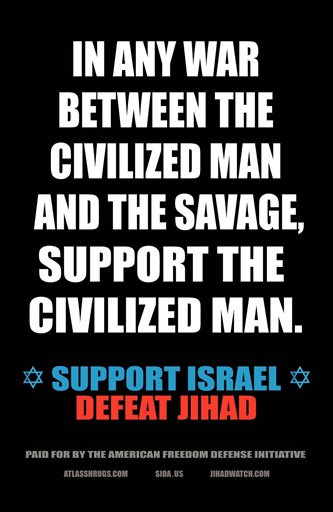

Meanwhile, in the United States, a lawsuit was moving through the courts concerning a deeply racist advertisement that “The American Freedom Defense Initiative” wanted to pay to have displayed by New York City’s subway system (MTA). The MTA went to the courts in an effort to block the advertisement which implicitly linked Muslims to savages. The MTA lost their court battle when a judge argued that this racist ad was protected speech, thereby forcing the MTA to accept and post the advertisements. Begrudgingly, they did. And this is where we get to Mona.

Meanwhile, in the United States, a lawsuit was moving through the courts concerning a deeply racist advertisement that “The American Freedom Defense Initiative” wanted to pay to have displayed by New York City’s subway system (MTA). The MTA went to the courts in an effort to block the advertisement which implicitly linked Muslims to savages. The MTA lost their court battle when a judge argued that this racist ad was protected speech, thereby forcing the MTA to accept and post the advertisements. Begrudgingly, they did. And this is where we get to Mona.

While posting racist images is covered under free speech law, not just any act is covered under the freedom of expression. When Eltahawy chose to express her dissent by spray painting the ads, she did commit a crime, just as anyone who graffitis any public property is committing a crime. Freedom of speech does not permit anyone to damage property and, as horrid as those ads are, they were the property of the MTA. Unfortunately for Eltahawy, her act is also not non-violent protest because she committed a crime. [Update: Eltahawy uses non-violent protest as her justification to the police officers for why she should not be arrested. I’m not suggesting that her act was violent, but rather, that she can’t claim that she’s simply engaged in non-violent protest and assume that this overrides the illegal nature of her actions. If she knows her actions are illegal, she can claim she’s engaged in civil disobedience, but civil disobedience and non-violent protest are not synonymous.] Had she chosen to stand in front of the ad and said whatever was on her mind, she would’ve been fully within her rights (provided that it did not escalate to “disturbing the peace”). Now, we might not like that vandalism is a crime – and we might recognize that most graffiti these days goes unpunished – but the fact is that spray painting public property is unquestionably illegal.

Of course, the whole thing reaches a new level of disgusting today when Pamela Hall – the anti-Islam activist behind “Stop the Islamization of America” – sues Eltahawy for damage to _her_ property. While I don’t believe that Eltahawy was in the right when she vandalized MTA property, the video makes it very clear that Hall actively provokes Eltahawy and because of Hall’s aggressions, Hall’s property is damaged. I hope that the courts throw this one out entirely.

Making Protests Visible

By circulating the video of Eltahawy getting arrested, activists are asking viewers to have sympathy with Eltahawy. In some ways, this isn’t hard. That poster is disgusting and I’m embarrassed by it. But her choice to consistently exclaim that she’s engaged in freedom of expression and non-violent protest is misleading and inaccurate. What she did, whether she knew it or not, was illegal and not within the dominion of either free speech or non-violent protest. Interestingly, her aggressive interlocutor accepts her frame and just keeps trying to negate it by saying that she’s “violating free speech.” This too is inaccurate. Free speech is not the issue at play in the altercation between Eltahawy and Hall or when Eltahawy vandalizes the poster. Free speech only matters in that that stupid poster was posted in the first place.

The legal details of this will get worked out in the court, but I’m bothered by the way in which the circulation of this video and the discussion around it polarizes the conversation without shedding light on the murky realities of how free speech operates of what is and is not free speech and of what is and is not illegal in the United States when it comes to protesting. Let me be clear: I think that we should all be protesting those racist ads. And I’m fully aware that some acts of protest can and must blur the lines between what is legal and illegal because law enforcement regularly suppresses protester’s rights and arrests people in oppressive ways that undermine important acts of resistance. And I also realize that one of the reasons that activists engage in acts that get them arrested because, when they do, news media covers it and bringing attention to an issue is often a desired end-goal by many activists. But what concerns me is that there’s a huge international disconnect brewing over American free speech and our failure to publicly untangle these issues undermines any effort to promote its value.

I’m deeply committed to the value of free speech. I understand its costs and I despise when it’s used as a tool to degrade and demean people or groups. I hate when it’s used to justify unhealthy behavior or reinforce norms that disgust me. But I tolerate these things because I believe that it’s one of the most critical tools of freedom. I firmly believe that censoring speech erodes a society more than allowing icky speech does. I also firmly believe that efforts to hamper free speech do a greater disservice to oppressed people than permitting disgusting speech. It’s a trade-off and it’s a trade-off that I accept. Yet, it’s also a trade-off that cannot be taken for granted, especially in a global society.

Through the internet, content spreads across boundaries and cultural contexts. It’s sooo easy to take things out of context or not understand the context in which they are produced or disseminated. Or why they are tolerated. Contexts collapse and people get upset because their local norms and rules don’t seem to apply when things slip over the borders and can’t be controlled. Thus, we see a serious battle brewing over who controls the internet. What norms? What laws? What cultural contexts? Settling this is really bloody hard because many of the issues at stake are so deeply conflicting as to appear to be irresolvable.

I genuinely don’t know what’s going to happen to freedom of speech as we enter into a networked world, but I suspect it’s going to spark many more ugly confrontations. Rather, it’s not the freedom of speech itself that will, but the visibility of the resultant expressions, good, bad, and ugly. For this reason, I think that we need to start having a serious conversation about what freedom of speech means in a networked world where jurisdictions blur, norms collide, and contexts collapse. This isn’t going to be worked out by enacting global laws nor is it going to be easily solved through technology. This is, above all else, a social issue that has scaled to new levels, creating serious socio-cultural governance questions. How do we understand the boundaries and freedoms of expression in a networked world?

Meanwhile, in the United States, a lawsuit was moving through the courts concerning a deeply racist advertisement that “The American Freedom Defense Initiative” wanted to pay to have displayed by New York City’s subway system (MTA). The MTA went to the courts in an effort to block the advertisement which implicitly linked Muslims to savages. The MTA lost their court battle when a judge argued that this racist ad was protected speech, thereby forcing the MTA to accept and post the advertisements. Begrudgingly, they did. And this is where we get to Mona.

Meanwhile, in the United States, a lawsuit was moving through the courts concerning a deeply racist advertisement that “The American Freedom Defense Initiative” wanted to pay to have displayed by New York City’s subway system (MTA). The MTA went to the courts in an effort to block the advertisement which implicitly linked Muslims to savages. The MTA lost their court battle when a judge argued that this racist ad was protected speech, thereby forcing the MTA to accept and post the advertisements. Begrudgingly, they did. And this is where we get to Mona.