Anxious about the widespread consumption and spread of propaganda and fake news during this year’s election cycle, many progressives are calling for an increased commitment to media literacy programs. Others are clamoring for solutions that focus on expert fact-checking and labeling. Both of these approaches are likely to fail — not because they are bad ideas, but because they fail to take into consideration the cultural context of information consumption that we’ve created over the last thirty years. The problem on our hands is a lot bigger than most folks appreciate.

What Are Your Sources?

I remember a casual conversation that I had with a teen girl in the midwest while I was doing research. I knew her school approached sex ed through an abstinence-only education approach, but I don’t remember how the topic of pregnancy came up. What I do remember is her telling me that she and her friends talked a lot about pregnancy and “diseases” she could get through sex. As I probed further, she matter-of-factly explained a variety of “facts” she had heard that were completely inaccurate. You couldn’t get pregnant until you were 16. AIDS spreads through kissing. Etc. I asked her if she’d talked to her doctor about any of this, and she looked me as though I had horns. She explained that she and her friends had done the research themselves, by which she meant that they’d identified websites online that “proved” their beliefs.

For years, that casual conversation has stuck with me as one of the reasons that we needed better Internet-based media literacy. As I detailed in my book It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens, too many students I met were being told that Wikipedia was untrustworthy and were, instead, being encouraged to do research. As a result, the message that many had taken home was to turn to Google and use whatever came up first. They heard that Google was trustworthy and Wikipedia was not.

Understanding what sources to trust is a basic tenet of media literacy education. When educators encourage students to focus on sourcing quality information, they encourage them to critically ask who is publishing the content. Is the venue a respected outlet? What biases might the author have? The underlying assumption in all of this is that there’s universal agreement that major news outlets like the New York Times, scientific journal publications, and experts with advanced degrees are all highly trustworthy.

Think about how this might play out in communities where the “liberal media” is viewed with disdain as an untrustworthy source of information…or in those where science is seen as contradicting the knowledge of religious people…or where degrees are viewed as a weapon of the elite to justify oppression of working people. Needless to say, not everyone agrees on what makes a trusted source.

Students are also encouraged to reflect on economic and political incentives that might bias reporting. Follow the money, they are told. Now watch what happens when they are given a list of names of major power players in the East Coast news media whose names are all clearly Jewish. Welcome to an opening for anti-Semitic ideology.

Empowered Individuals…with Guns

We’ve been telling young people that they are the smartest snowflakes in the world. From the self-esteem movement in the 1980s to the normative logic of contemporary parenting, young people are told that they are lovable and capable and that they should trust their gut to make wise decisions. This sets them up for another great American ideal: personal responsibility.

In the United States, we believe that worthy people lift themselves up by their bootstraps. This is our idea of freedom. What it means in practice is that every individual is supposed to understand finance so well that they can effectively manage their own retirement funds. And every individual is expected to understand their health risks well enough to make their own decisions about insurance. To take away the power of individuals to control their own destiny is viewed as anti-American by so much of this country. You are your own master.

Children are indoctrinated into this cultural logic early, even as their parents restrict their mobility and limit their access to social situations. But when it comes to information, they are taught that they are the sole proprietors of knowledge. All they have to do is “do the research” for themselves and they will know better than anyone what is real.

Combine this with a deep distrust of media sources. If the media is reporting on something, and you don’t trust the media, then it is your responsibility to question their authority, to doubt the information you are being given. If they expend tremendous effort bringing on “experts” to argue that something is false, there must be something there to investigate.

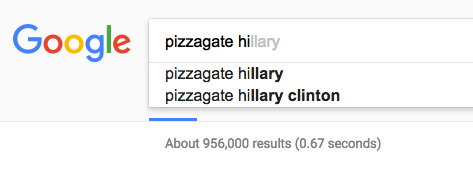

Now think about what this means for #Pizzagate. Across this country, major news outlets went to great effort to challenge conspiracy reports that linked John Podesta and Hillary Clinton to a child trafficking ring supposedly run out of a pizza shop in Washington, DC. Most people never heard the conspiracy stories, but their ears perked up when the mainstream press went nuts trying to debunk these stories. For many people who distrust “liberal” media and were already primed not to trust Clinton, the abundant reporting suggested that there was something to investigate.

Most people who showed up to the Comet Ping Pong pizzeria to see for their own eyes went undetected. But then a guy with a gun decided he “wanted to do some good” and “rescue the children.” He was the first to admit that “the intel wasn’t 100%,” but what he was doing was something that we’ve taught people to do — question the information they’re receiving and find out the truth for themselves.

Experience Over Expertise

Many marginalized groups are justifiably angry about the ways in which their stories have been dismissed by mainstream media for decades. This is most acutely felt in communities of color. And this isn’t just about the past. It took five days for major news outlets to cover Ferguson. It took months and a lot of celebrities for journalists to start discussing the Dakota Pipeline. But feeling marginalized from news media isn’t just about people of color. For many Americans who have watched their local newspaper disappear, major urban news reporting appears disconnected from reality. The issues and topics that they feel affect their lives are often ignored.

For decades, civil rights leaders have been arguing for the importance of respecting experience over expertise, highlighting the need to hear the voices of people of color who are so often ignored by experts. This message has taken hold more broadly, particularly among lower and middle class whites who feel as though they are ignored by the establishment. Whites also want their experiences to be recognized, and they too have been pushing for the need to understand and respect the experiences of “the common man.” They see “liberal” “urban” “coastal” news outlets as antithetical to their interests because they quote from experts, use cleaned-up pundits to debate issues, and turn everyday people (e.g., “red sweater guy”) into spectacles for mass enjoyment.

Consider what’s happening in medicine. Many people used to have a family doctor whom they knew for decades and trusted as individuals even more than as experts. Today, many people see doctors as arrogant and condescending, overly expensive and inattentive to their needs. Doctors lack the time to spend more than a few minutes with patients, and many people doubt that the treatment they’re getting is in their best interest. People feel duped into paying obscene costs for procedures that they don’t understand. Many economists can’t understand why so many people would be against the Affordable Care Act because they don’t recognize that this “socialized” medicine is perceived as experts over experience by people who don’t trust politicians who tell them what’s in their best interest any more than they trust doctors. And public trust in doctors is declining sharply.

Why should we be surprised that most people are getting medical information from their personal social network and the Internet? It’s a lot cheaper than seeing a doctor, and both friends and strangers on the Internet are willing to listen, empathize, and compare notes. Why trust experts when you have at your fingertips a crowd of knowledgeable people who may have had the same experience as you and can help you out?

Consider this dynamic in light of discussions around autism and vaccinations. First, an expert-produced journal article was published linking autism to vaccinations. This resonated with many parents’ experience. Then, other experts debunked the first report, challenged the motivations of the researcher, and engaged in a mainstream media campaign to “prove” that there was no link. What unfolded felt like a war on experience, and a network of parents coordinated to counter this new batch of experts who were widely seen as ignorant, moneyed, and condescending. The more that the media focused on waving away these networks of parents through scientific language, the more the public felt sympathetic to the arguments being made by anti-vaxxers.

Keep in mind that anti-vaxxers aren’t arguing that vaccinations definitively cause autism. They are arguing that we don’t know. They are arguing that experts are forcing children to be vaccinated against their will, which sounds like oppression. What they want is choice — the choice to not vaccinate. And they want information about the risks of vaccination, which they feel are not being given to them. In essence, they are doing what we taught them to do: questioning information sources and raising doubts about the incentives of those who are pushing a single message. Doubt has become tool.

Grappling with “Fake News”

Since the election, everyone has been obsessed with fake news, as experts blame “stupid” people for not understanding what is “real.” The solutionism around this has been condescending at best. More experts are needed to label fake content. More media literacy is needed to teach people how not to be duped. And if we just push Facebook to curb the spread of fake news, all will be solved.

I can’t help but laugh at the irony of folks screaming up and down about fake news and pointing to the story about how the Pope backs Trump. The reason so many progressives know this story is because it was spread wildly among liberal circles who were citing it as appalling and fake. From what I can gather, it seems as though liberals were far more likely to spread this story than conservatives. What more could you want if you ran a fake news site whose goal was to make money by getting people to spread misinformation? Getting doubters to click on clickbait is far more profitable than getting believers because they’re far more likely to spread the content in an effort to dispel the content. Win!

People believe in information that confirms their priors. In fact, if you present them with data that contradicts their beliefs, they will double down on their beliefs rather than integrate the new knowledge into their understanding. This is why first impressions matter. It’s also why asking Facebook to show content that contradicts people’s views will not only increase their hatred of Facebook but increase polarization among the network. And it’s precisely why so many liberals spread “fake news” stories in ways that reinforce their belief that Trump supporters are stupid and backwards.

Labeling the Pope story as fake wouldn’t have stopped people from believing that story if they were conditioned to believe it. Let’s not forget that the public may find Facebook valuable, but it doesn’t necessarily trust the company. So their “expertise” doesn’t mean squat to most people. Of course, it would be an interesting experiment to run; I do wonder how many liberals wouldn’t have forwarded it along if it had been clearly identified as fake. Would they have not felt the need to warn everyone in their network that conservatives were insane? Would they have not helped fuel a money-making fake news machine? Maybe.

But I think labeling would reinforce polarization — but it would feel like something was done. Nonbelievers would use the label to reinforce their view that the information is fake (and minimize the spread, which is probably a good thing), while believers would simply ignore the label. But does that really get us to where we want to go?

Addressing so-called fake news is going to require a lot more than labeling.It’s going to require a cultural change about how we make sense of information, whom we trust, and how we understand our own role in grappling with information. Quick and easy solutions may make the controversy go away, but they won’t address the underlying problems.

What Is Truth?

As a huge proponent for media literacy for over a decade, I’m struggling with the ways in which I missed the mark. The reality is that my assumptions and beliefs do not align with most Americans. Because of my privilege as a scholar, I get to see how expert knowledge and information is produced and have a deep respect for the strengths and limitations of scientific inquiry. Surrounded by journalists and people working to distribute information, I get to see how incentives shape information production and dissemination and the fault lines of that process. I believe that information intermediaries are important, that honed expertise matters, and that no one can ever be fully informed. As a result, I have long believed that we have to outsource certain matters and to trust others to do right by us as individuals and society as a whole. This is what it means to live in a democracy, but, more importantly, it’s what it means to live in a society.

In the United States, we’re moving towards tribalism, and we’re undoing the social fabric of our country through polarization, distrust, and self-segregation. And whether we like it or not, our culture of doubt and critique, experience over expertise, and personal responsibility is pushing us further down this path.

Media literacy asks people to raise questions and be wary of information that they’re receiving. People are. Unfortunately, that’s exactly why we’re talking past one another.

The path forward is hazy. We need to enable people to hear different perspectives and make sense of a very complicated — and in many ways, overwhelming — information landscape. We cannot fall back on standard educational approaches because the societal context has shifted. We also cannot simply assume that information intermediaries can fix the problem for us, whether they be traditional news media or social media. We need to get creative and build the social infrastructure necessary for people to meaningfully and substantively engage across existing structural lines. This won’t be easy or quick, but if we want to address issues like propaganda, hate speech, fake news, and biased content, we need to focus on the underlying issues at play. No simple band-aid will work.

Special thanks to Amanda Lenhart, Claire Fontaine, Mary Madden, and Monica Bulger for their feedback!

This post was first published as part of a series on media, accountability, and the public sphere. See also:

- Hacking the Attention Economy by danah boyd

- What’s Propaganda Got To Do With It? by Caroline Jack

- Are There Limits to Online Free Speech? by Alice Marwick

- Why America is Self-Segregating by danah boyd

- How do you deal with a problem like “fake news?” by Robyn Caplan