A pair of Gizmodo stories have prompted journalists to ask questions about Facebook’s power to manipulate political opinion in an already heated election year. If the claims are accurate, Facebook contractors have depressed some conservative news, and their curatorial hand affects the Facebook Trending list more than the public realizes. Mark Zuckerberg took to his Facebook page yesterday to argue that Facebook does everything possible to be neutral and that there are significant procedures in place to minimize biased coverage. He also promises to look into the accusations.

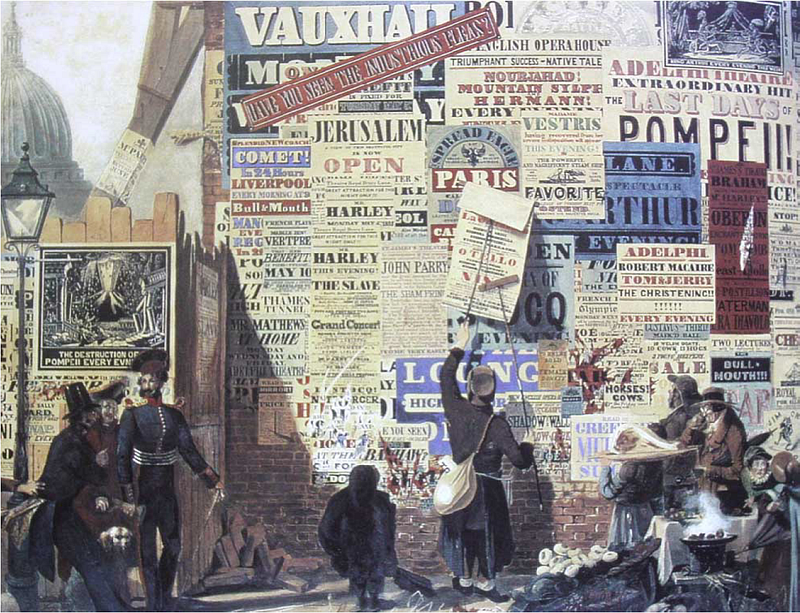

As this conversation swirls around intentions and explicit manipulation, there are some significant issues missing. First, all systems are biased. There is no such thing as neutrality when it comes to media. That has long been a fiction, one that traditional news media needs and insists on, even as scholars highlight that journalists reveal their biases through everything from small facial twitches to choice of frames and topics of interests. It’s also dangerous to assume that the “solution” is to make sure that “both” sides of an argument are heard equally. This is the source of tremendous conflict around how heated topics like climate change and evolution are covered. Itis even more dangerous, however, to think that removing humans and relying more on algorithms and automation will remove this bias.

Recognizing bias and enabling processes to grapple with it must be part of any curatorial process, algorithmic or otherwise. As we move into the development of algorithmic models to shape editorial decisions and curation, we need to find a sophisticated way of grappling with the biases that shape development, training sets, quality assurance, and error correction, not to mention an explicit act of “human” judgment.

There never was neutrality, and there never will be.

This issue goes far beyond the Trending box in the corner of your Facebook profile, and this latest wave of concerns is only the tip of the iceberg around how powerful actors can affect or shape political discourse. What is of concern right now is not that human beings are playing a role in shaping the news — they always have — it is the veneer of objectivity provided by Facebook’s interface, the claims of neutrality enabled by the integration of algorithmic processes, and the assumption that what is prioritized reflects only the interests and actions of the users (the “public sphere”) and not those of Facebook, advertisers, or other powerful entities.

The key challenge that emerges out of this debate concerns accountability.In theory, news media is accountable to the public. Like neutrality, this is more of a desired goal than something that’s consistently realized. While traditional news media has aspired to — but not always realized — meaningful accountability, there are a host of processes in place to address the possibility of manipulation: ombudspeople, whistleblowers, public editors, and myriad alternate media organizations. Facebook and other technology companies have not, historically, been included in that conversation.

I have tremendous respect for Mark Zuckerberg, but I think his stance that Facebook will be neutral as long as he’s in charge is a dangerous statement.This is what it means to be a benevolent dictator, and there are plenty of people around the world who disagree with his values, commitments, and logics. As a progressive American, I have a lot more in common with Mark than not, but I am painfully aware of the neoliberal American value systems that are baked into the very architecture of Facebook and our society as a whole.

Who Controls the Public Sphere in an Era of Algorithms?

In light of this public conversation, I’m delighted to announce that Data & Society has been developing a project that asks who controls the public sphere in an era of algorithms. As part of this process, we convened a workshop and have produced a series of documents that we think are valuable to the conversation:

- Mediation, Automation, Power, a contemporary issues primer

- Assumptions and Questions, a background primer

- Case Studies, a complement to the contemporary issues primer

- Executive Summary for Workshop

- Workshop Summary, extended notes from the workshop

These documents provide historical context, highlight how media has always been engaged in power struggles, showcase the challenges that new media face, and offer case studies that reveal the complexities going forward.

This conversation is by no means over. It is only just beginning. My hope is that we quickly leave the state of fear and start imagining mechanisms of accountability that we, as a society, can live with. Institutions like Facebook have tremendous power and they can wield that power for good or evil. Butfor society to function responsibly, there must be checks and balances regardless of the intentions of any one institution or its leader.

This work is a part of Data & Society’s developing Algorithms and Publics project, including a set of documents occasioned by the Who Controls the Public Sphere in an Era of Algorithms? workshop. More posts from workshop participants:

- Ben Franklin, the Post Office and the Digital Public Sphere by Ethan Zuckerman

- No More Magic Algorithms: Cultural Policy in an Era of Discoverabilityby Fenwick McKelvey

- Questions about Google autocompl by Robyn Caplan

At what age should children be allowed to access the internet without parental oversight? This is a hairy question that raises all sorts of issues about rights, freedoms, morality, skills, and cognitive capability. Cultural values also come into play full force on this one.

At what age should children be allowed to access the internet without parental oversight? This is a hairy question that raises all sorts of issues about rights, freedoms, morality, skills, and cognitive capability. Cultural values also come into play full force on this one.

It seems that student privacy is trendy right now. At least among elected officials. Congressional aides are scrambling to write bills that one-up each other in showcasing how tough they are on protecting youth. We’ve got Congressmen

It seems that student privacy is trendy right now. At least among elected officials. Congressional aides are scrambling to write bills that one-up each other in showcasing how tough they are on protecting youth. We’ve got Congressmen  Throughout

Throughout