Earlier this week, the Wall Street Journal posted excerpts from a debate between me, Stewart Baker, Jeff Jarvis, and Chris Soghoian on privacy. In preparation for the piece, they had us respond to a series of questions. Jeff posted the full text of his responses here. Now it’s my turn. Here are the questions that I was asked and my responses.

Part 1:

Question: How much should people care about privacy? (400 words)

People should – and do – care deeply about privacy. But privacy is not simply the control of information. Rather, privacy is the ability to assert control over a social situation. This requires that people have agency in their environment and that they are able to understand any given social situation so as to adjust how they present themselves and determine what information they share. Privacy violations occur when people have their agency undermined or lack relevant information in a social setting that’s needed to act or adjust accordingly. Privacy is not protected by complex privacy settings that create what Alessandro Acquisti calls “the illusion of control.” Rather, it’s protected when people are able to fully understand the social environment in which they are operating and have the protections necessary to maintain agency.

Social media has prompted a radical shift. We’ve moved from a world that is “private-by-default, public-through-effort” to one that is “public-by-default, private-with-effort.” Most of our conversations in a face-to-face setting are too mundane for anyone to bother recording and publicizing. They stay relatively private simply because there’s no need or desire to make them public. Online, social technologies encourage broad sharing and thus, participating on sites like Facebook or Twitter means sharing to large audiences. When people interact casually online, they share the mundane. They aren’t publicizing; they’re socializing. While socializing, people have no interest in going through the efforts required by digital technologies to make their pithy conversations more private. When things truly matter, they leverage complex social and technical strategies to maintain privacy.

The strategies that people use to assert privacy in social media are diverse and complex, but the most notable approach involves limiting access to meaning while making content publicly accessible. I’m in awe of the countless teens I’ve met who use song lyrics, pronouns, and community references to encode meaning into publicly accessible content. If you don’t know who the Lions are or don’t know what happened Friday night or don’t know why a reference to Rihanna’s latest hit might be funny, you can’t interpret the meaning of the message. This is privacy in action.

The reason that we must care about privacy, especially in a democracy, is that it’s about human agency. To systematically undermine people’s privacy – or allow others to do so – is to deprive people of freedom and liberty.

Part 2:

Question: What is the harm in not being able to control our social contexts? Do we suffer because we have to develop codes to communicate on social networks? Or are we forced offline because of our inability to develop codes? (200 words)

Social situations are not one-size-fits-all. How a man acts with his toddler son is different from how he interacts with his business partner, not because he’s trying to hide something but because what’s appropriate in each situation differs. Rolling on the floor might provoke a giggle from his toddler, but it would be strange behavior in a business meeting. When contexts collide, people must choose what’s appropriate. Often, they present themselves in a way that’s as inoffensive to as many people as possible (and particularly those with high social status), which often makes for a bored and irritable toddler.

Social media is one big context collapse, but it’s not fun to behave as though being online is a perpetual job interview. Thus, many people lower their guards and try to signal what context they want to be in, hoping others will follow suit. When that’s not enough, they encode their messages to be only relevant to a narrower audience. This is neither good, nor bad; it’s simply how people are learning to manage their lives in a networked world where they cannot assume strict boundaries between distinct contexts. Lacking spatial separation, people construct context through language and interaction.

Part 3:

Question: Jeff and Stewart seem to be arguing that privacy advocates have too much power and that they should be reined in for the good of society. What do you think of that view? Is the status quo protecting privacy enough? So we need more laws? What kind of laws? Or different social norms? In particular, I would like to hear what you think should be done to prevent turning the Internet into one long job interview, as you described. If you had one or two examples of types of usages that you think should be limited, that would be perfect. (300 words)

When it comes to creating a society in which both privacy and public life can flourish, there are no easy answers. Laws can protect, but they can also hinder. Technologies can empower, but they can also expose. I respect my esteemed colleagues’ views, but I am also concerned about what it means to have a conversation among experts. Decisions about privacy – and public life – in a networked age are being made by people who have immense social, political, and/or economic power, often at the expense of those who are less privileged. We must engender a public conversation about these issues rather than leaving the in the hands of experts.

There are significant pros and cons to all social, legal, economic, and technological decisions. Balancing individual desires with the goals of the collective is daunting. Mediated life forces us to face serious compromises and hard choices. Privacy is a value that’s dear to many people, precisely because openness is a privilege. Systems must respect privacy, but there’s no easy mechanism to inscribe this value into code or law. Thus, we must publicly grapple with these issues and put pressure on decision-makers and systems-builders to remember that their choices have consequences.

We must also switch the conversation from being about one of data collection to being one about data usage. This involves drawing on the language of abuse, violence, and victimization to think about what happens when people’s willingness to share is twisted to do them harm. Just as we have models for differentiating sex between consenting partners and rape, so too must we construct models that that separate usage that’s empowering and that which strips people of their freedoms and opportunities. For example, refusing health insurance based on search queries may make economic sense, but the social costs are far to great. Focusing on usage requires understanding who is doing what to whom and for what purposes. Limiting data collection may be structurally easier, but it doesn’t address the tensions between privacy and public-ness with which people are struggling.

Part 4:

Question: Jeff makes the point that we’re overemphasizing privacy at the expense of all the public benefits delivered by new online services. What do you think of that view? Do you think privacy is being sufficiently protected?

I think that positioning privacy and public-ness in opposition is a false dichotomy. People want privacy *and* they want to be able to participate in public. This is why I think it’s important to emphasize that privacy is not about controlling information, but about having agency and the ability to control a social situation. People want to share and they gain a lot from sharing. But that’s different than saying that people want to be exposed by others. Agency matters.

From my perspective, protecting privacy is about making certain that people have the agency they need to make informed decisions about how they engage in public. I do not think that we’ve done enough here. That said, I am opposed to approaches that protect people by disempowering them or by taking away their agency. I want to see approaches that force powerful entities to be transparent about their data practices. And I want to see approaches the put restrictions on how data can be used to harm people. For example, people should have the ability to share their medical experiences without being afraid of losing their health insurance. The answer is not to silence consumers from sharing their experiences, but rather to limit what insurers can do with information that they can access.

Question: Jeff says that young people are “likely the worst-served sector of society online”? What do you think of that? Do youth-targeted privacy safeguards prevent them from taking advantage of the benefits of the online world? Do the young have special privacy issues, and do they deserve special protections?

I _completely_ agree with Jeff on this point. In our efforts to protect youth, we often exclude them from public life. Nowhere is this more visible than with respect to the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA). This well-intended laws was meant to empower parents. Yet, in practice, it has prompted companies to ban any child under the age of 13 from joining general-purpose communication services and participating on social media platforms. In other words, COPPA has inadvertently locked children out of being legitimate users of Facebook, Gmail, Skype, and similar services. Interestingly, many parents help their children circumvent age restrictions. Is this a win? I don’t think so.

I don’t believe that privacy protections focused on children make any sense. Yes, children are a vulnerable population, but they’re not the only vulnerable population. Can you imagine excluding senile adults from participating on Facebook because they don’t know when they’re being manipulated? We need to develop structures that support all people while also making sure that protection does not equal exclusion.

Thanks to Julia Angwin for keeping us on task!

Networked technologies – including the internet, mobile phones, and social media – alter how information flows and how people communicate. There is little doubt that technology is increasingly playing a role in the practices and processes surrounding human trafficking: the illegal trade of people for commercial sexual exploitation, forced labor, and other forms of modern-day slavery. Yet, little is known about costs and benefits of technology’s role. We do not know if there are more human trafficking victims as a result of technology, nor do we know if law enforcement can identify perpetrators better as a result of the traces that they leave. One thing that we do know is that technology makes many aspects of human trafficking more visible and more traceable, for better and for worse. Focusing on whether technology is good or bad misses the point; it is here to stay and it is imperative that we understand the role that it is playing. More importantly, we need to develop innovative ways of using technology to address the horrors of human trafficking.

Networked technologies – including the internet, mobile phones, and social media – alter how information flows and how people communicate. There is little doubt that technology is increasingly playing a role in the practices and processes surrounding human trafficking: the illegal trade of people for commercial sexual exploitation, forced labor, and other forms of modern-day slavery. Yet, little is known about costs and benefits of technology’s role. We do not know if there are more human trafficking victims as a result of technology, nor do we know if law enforcement can identify perpetrators better as a result of the traces that they leave. One thing that we do know is that technology makes many aspects of human trafficking more visible and more traceable, for better and for worse. Focusing on whether technology is good or bad misses the point; it is here to stay and it is imperative that we understand the role that it is playing. More importantly, we need to develop innovative ways of using technology to address the horrors of human trafficking.  Announcing new journal article:

Announcing new journal article:

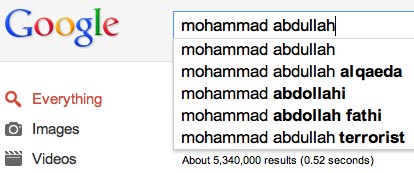

You’re a 16-year-old Muslim kid in America. Say your name is Mohammad Abdullah. Your schoolmates are convinced that you’re a terrorist. They keep typing in Google queries likes “is Mohammad Abdullah a terrorist?” and “Mohammad Abdullah al Qaeda.” Google’s search engine learns. All of a sudden, auto-complete starts suggesting terms like “Al Qaeda” as the next term in relation to your name. You know that colleges are looking up your name and you’re afraid of the impression that they might get based on that auto-complete. You are already getting hostile comments in your hometown, a decidedly anti-Muslim environment. You know that you have nothing to do with Al Qaeda, but Google gives the impression that you do. And people are drawing that conclusion. You write to Google but nothing comes of it. What do you do?

You’re a 16-year-old Muslim kid in America. Say your name is Mohammad Abdullah. Your schoolmates are convinced that you’re a terrorist. They keep typing in Google queries likes “is Mohammad Abdullah a terrorist?” and “Mohammad Abdullah al Qaeda.” Google’s search engine learns. All of a sudden, auto-complete starts suggesting terms like “Al Qaeda” as the next term in relation to your name. You know that colleges are looking up your name and you’re afraid of the impression that they might get based on that auto-complete. You are already getting hostile comments in your hometown, a decidedly anti-Muslim environment. You know that you have nothing to do with Al Qaeda, but Google gives the impression that you do. And people are drawing that conclusion. You write to Google but nothing comes of it. What do you do?