We all know that teen bullying – both online and offline – has devastating consequences. Jamey Rodemeyer’s suicide is a tragedy. He was tormented for being gay. He knew he was being bullied and he regularly talked about the fact that he was being bullied. Online, he even wrote: “I always say how bullied I am, but no one listens. What do I have to do so people will listen to me?” The fact that he could admit that he was being tormented coupled with the fact that he asked for help and folks didn’t help him should be a big wake-up call. We have a problem. And that problem is that most of us adults don’t have the foggiest clue how to help youth address bullying.

We all know that teen bullying – both online and offline – has devastating consequences. Jamey Rodemeyer’s suicide is a tragedy. He was tormented for being gay. He knew he was being bullied and he regularly talked about the fact that he was being bullied. Online, he even wrote: “I always say how bullied I am, but no one listens. What do I have to do so people will listen to me?” The fact that he could admit that he was being tormented coupled with the fact that he asked for help and folks didn’t help him should be a big wake-up call. We have a problem. And that problem is that most of us adults don’t have the foggiest clue how to help youth address bullying.

It doesn’t take a tragedy to know that we need to find a way to combat bullying. Countless regulators and educators are desperate to do something – anything – to put an end to the victimization. But in their desperation to find a solution, they often turn a blind’s eye to both research and the voices of youth.

The canonical research definition of bullying was written by Olweus and it has three components:

- Bullying is aggressive behavior that involves unwanted, negative actions.

- Bullying involves a pattern of behavior repeated over time.

- Bullying involves an imbalance of power or strength.

What Rodemeyer faced was clearly bullying, but a lot of the reciprocal relational aggression that teens experience online is not actually bullying. Still, in the public eye, these concepts are blurred and so when parents and teachers and regulators talk about wanting to stop bullying, they talk about wanting to stop all forms of relational aggression too. The problem is that many teens do not – and, for good reasons, cannot – identify a lot of what they experience as bullying. Thus, all of the new fangled programs to stop bullying are often missing the mark entirely. In a new paper that Alice Marwick and I co-authored – called “The Drama! Teen Conflict, Gossip, and Bullying in Networked Publics” – we analyzed the language of youth and realized that their use the language of “drama” serves many purposes, not the least of which is to distance themselves from the perpetrator / victim rhetoric of bullying in order to save face and maintain agency.

For most teenagers, the language of bullying does not resonate. When teachers come in and give anti-bullying messages, it has little effect on most teens. Why? Because most teens are not willing to recognize themselves as a victim or as an aggressor. To do so would require them to recognize themselves as disempowered or abusive. They aren’t willing to go there. And when they are, they need support immediately. Yet, few teens have the support structures necessary to make their lives better. Rodemeyer is a case in point. Few schools have the resources to provide youth with the necessary psychological counseling to work through these issues. But if we want to help youth who are bullied, we need there to be infrastructure to help young people when they are willing to recognize themselves as victimized.

To complicate matters more, although school after school is scrambling to implement anti-bullying programs, no one is assessing the effectiveness of these programs. This is not to say that we don’t need education – we do. But we need the interventions to be tested. And my educated hunch is that we need to be focusing more on positive frames that use the language of youth rather than focusing on the negative.

I want to change the frame of our conversation because we need to change the frame if we’re going to help youth. I’ve spent the last seven years talking to youth about bullying and drama and it nearly killed me when I realized that all of the effort that adults are putting into anti-bullying campaigns are falling on deaf ears and doing little to actually address what youth are experiencing. Even hugely moving narratives like “It Gets Better” aren’t enough when a teen can make a video for other teens and then kill himself because he’s unable to make it better in his own community.

In an effort to ground the bullying conversation, Alice Marwick and I just released a draft of our new paper: “The Drama! Teen Conflict, Gossip, and Bullying in Networked Publics.” We also co-authored a New York Times Op-Ed in the hopes of reaching a wider audience: “Why Cyberbullying Rhetoric Misses the Mark.” Please read these and send us feedback or criticism. We are in this to help the youth that we spend so much time with and we’re both deeply worried that adult rhetoric is going in the wrong direction and failing to realize why it’s counterproductive.

Image from Flickr by Brandon Christopher Warren

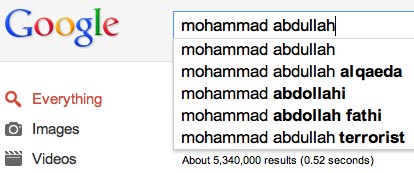

You’re a 16-year-old Muslim kid in America. Say your name is Mohammad Abdullah. Your schoolmates are convinced that you’re a terrorist. They keep typing in Google queries likes “is Mohammad Abdullah a terrorist?” and “Mohammad Abdullah al Qaeda.” Google’s search engine learns. All of a sudden, auto-complete starts suggesting terms like “Al Qaeda” as the next term in relation to your name. You know that colleges are looking up your name and you’re afraid of the impression that they might get based on that auto-complete. You are already getting hostile comments in your hometown, a decidedly anti-Muslim environment. You know that you have nothing to do with Al Qaeda, but Google gives the impression that you do. And people are drawing that conclusion. You write to Google but nothing comes of it. What do you do?

You’re a 16-year-old Muslim kid in America. Say your name is Mohammad Abdullah. Your schoolmates are convinced that you’re a terrorist. They keep typing in Google queries likes “is Mohammad Abdullah a terrorist?” and “Mohammad Abdullah al Qaeda.” Google’s search engine learns. All of a sudden, auto-complete starts suggesting terms like “Al Qaeda” as the next term in relation to your name. You know that colleges are looking up your name and you’re afraid of the impression that they might get based on that auto-complete. You are already getting hostile comments in your hometown, a decidedly anti-Muslim environment. You know that you have nothing to do with Al Qaeda, but Google gives the impression that you do. And people are drawing that conclusion. You write to Google but nothing comes of it. What do you do?