The United States has always been a diverse but segregated country. This has shaped American politics profoundly. Yet, throughout history, Americans have had to grapple with divergent views and opinions, political ideologies, and experiences in order to function as a country. Many of the institutions that underpin American democracy force people in the United States to encounter difference. This does not inherently produce tolerance or result in healthy resolution. Hell, the history of the United States is fraught with countless examples of people enslaving and oppressing other people on the basis of difference. This isn’t about our past; this is about our present. And today’s battles over laws and culture are nothing new.

Ironically, in a world in which we have countless tools to connect, we are also watching fragmentation, polarization, and de-diversification happen en masse. The American public is self-segregating, and this is tearing at the social fabric of the country.

Many in the tech world imagined that the Internet would connect people in unprecedented ways, allow for divisions to be bridged and wounds to heal.It was the kumbaya dream. Today, those same dreamers find it quite unsettling to watch as the tools that were designed to bring people together are used by people to magnify divisions and undermine social solidarity. These tools were built in a bubble, and that bubble has burst.

Nowhere is this more acute than with Facebook. Naive as hell, Mark Zuckerberg dreamed he could build the tools that would connect people at unprecedented scale, both domestically and internationally. I actually feel bad for him as he clings to that hope while facing increasing attacks from people around the world about the role that Facebook is playing in magnifying social divisions. Although critics love to paint him as only motivated by money, he genuinely wants to make the world a better place and sees Facebook as a tool to connect people, not empower them to self-segregate.

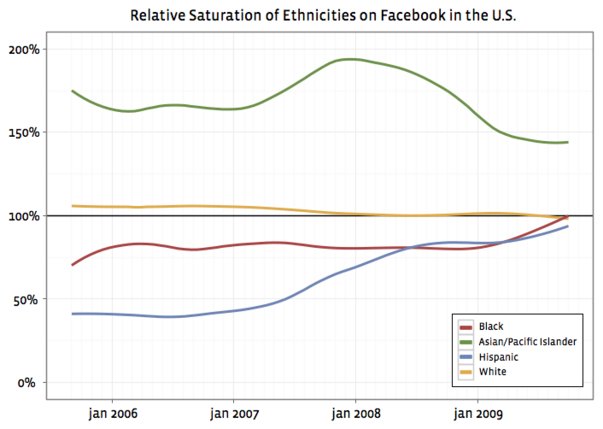

The problem is not simply the “filter bubble,” Eli Pariser’s notion that personalization-driven algorithmic systems help silo people into segregated content streams. Facebook’s claim that content personalization plays a small role in shaping what people see compared to their own choices is accurate.And they have every right to be annoyed. I couldn’t imagine TimeWarner being blamed for who watches Duck Dynasty vs. Modern Family. And yet, what Facebook does do is mirror and magnify a trend that’s been unfolding in the United States for the last twenty years, a trend of self-segregation that is enabled by technology in all sorts of complicated ways.

The United States can only function as a healthy democracy if we find a healthy way to diversify our social connections, if we find a way to weave together a strong social fabric that bridges ties across difference.

Yet, we are moving in the opposite direction with serious consequences. To understand this, let’s talk about two contemporary trend lines and then think about the implications going forward.

Privatizing the Military

The voluntary US military is, in many ways, a social engineering project. The public understands the military as a service organization, dedicated to protecting the country’s interests. Yet, when recruits sign up, they are promised training and job opportunities. Individual motivations vary tremendously, but many are enticed by the opportunity to travel the world, participate in a cause with a purpose, and get the heck out of dodge. Everyone expects basic training to be physically hard, but few recognize that some of the most grueling aspects of signing up have to do with the diversification project that is central to the formation of the American military.

When a soldier is in combat, she must trust her fellow soldiers with her life. And she must be willing to do what it takes to protect the rest of her unit. In order to make that possible, the military must wage war on prejudice. This is not an easy task. Plenty of generals fought hard to fight racial desegregation and to limit the role of women in combat. Yet, the US military was desegregated in 1948, six years before Brown v. Board forced desegregation of schools. And the Supreme Court ruled that LGB individuals could openly serve in the military before they could legally marry.

Morale is often raised as the main reason that soldiers should not be forced to entrust their lives to people who are different than them. Yet, time and again, this justification collapses under broader interests to grow the military. As a result, commanders are forced to find ways to build up morale across difference, to actively and intentionally seek to break down barriers to teamwork, and to find a way to gel a group of people whose demographics, values, politics, and ideologies are as varied as the country’s.

In the process, they build one of the most crucial social infrastructures of the country. They build the diverse social fabric that underpins democracy.

Tons of money was poured into defense after 9/11, but the number of people serving in the US military today is far lower than it was throughout the 1980s. Why? Starting in the 1990s and accelerating after 9/11, the US privatized huge chunks of the military. This means that private contractors and their employees play critical roles in everything from providing food services to equipment maintenance to military housing. The impact of this on the role of the military in society is significant. For example, this undermine recruits’ ability to get training to develop critical skills that will be essential for them in civilian life. Instead, while serving on active duty, they spend a much higher amount of time on the front lines and in high-risk battle, increasing the likelihood that they will be physically or psychologically harmed. The impact on skills development and job opportunities is tremendous, but so is the impact on the diversification of the social fabric.

Private vendors are not engaged in the same social engineering project as the military and, as a result, tend to hire and fire people based on their ability to work effectively as a team. Like many companies, they have little incentive to invest in helping diverse teams learn to work together as effectively as possible. Building diverse teams — especially ones in which members depend on each other for their survival — is extremely hard, time-consuming, and emotionally exhausting. As a result, private companies focus on “culture fit,” emphasize teams that get along, and look for people who already have the necessary skills, all of which helps reinforce existing segregation patterns.

The end result is that, in the last 20 years, we’ve watched one of our major structures for diversification collapse without anyone taking notice. And because of how it’s happened, it’s also connected to job opportunities and economic opportunity for many working- and middle-class individuals, seeding resentment and hatred.

A Self-Segregated College Life

If you ask a college admissions officer at an elite institution to describe how they build a class of incoming freshman, you will quickly realize that the American college system is a diversification project. Unlike colleges in most parts of the world, the vast majority of freshman at top tier universities in the United States live on campus with roommates who are assigned to them. Colleges approach housing assignments as an opportunity to pair diverse strangers with one another to build social ties. This makes sense given how many friendships emerge out of freshman dorms. By pairing middle class kids with students from wealthier families, elite institutions help diversify the elites of the future.

This diversification project produces a tremendous amount of conflict. Although plenty of people adore their college roommates and relish the opportunity to get to know people from different walks of life as part of their college experience, there is an amazing amount of angst about dorm assignments and the troubles that brew once folks try to live together in close quarters. At many universities, residential life is often in the business of student therapy as students complain about their roommates and dormmates. Yet, just like in the military, learning how to negotiate conflict and diversity in close quarters can be tremendously effective in sewing the social fabric.

In the springs of 2006, I was doing fieldwork with teenagers at a time when they had just received acceptances to college. I giggled at how many of them immediately wrote to the college in which they intended to enroll, begging for a campus email address so that they could join that school’s Facebook (before Facebook was broadly available). In the previous year, I had watched the previous class look up roommate assignments on MySpace so I was prepared for the fact that they’d use Facebook to do the same. What I wasn’t prepared for was how quickly they would all get on Facebook, map the incoming freshman class, and use this information to ask for a roommate switch. Before they even arrived on campus in August/September of 2006, they had self-segregated as much as possible.

A few years later, I watched another trend hit: cell phones. While these were touted as tools that allowed students to stay connected to parents (which prompted many faculty to complain about “helicopter parents” arriving on campus), they really ended up serving as a crutch to address homesickness, as incoming students focused on maintaining ties to high school friends rather than building new relationships.

Students go to elite universities to “get an education.” Few realize that the true quality product that elite colleges in the US have historically offered is social network diversification. Even when it comes to job acquisition, sociologists have long known that diverse social networks (“weak ties”) are what increase job prospects. By self-segregating on campus, students undermine their own potential while also helping fragment the diversity of the broader social fabric.

Diversity is Hard

Diversity is often touted as highly desirable. Indeed, in professional contexts, we know that more diverse teams often outperform homogeneous teams. Diversity also increases cognitive development, both intellectually and socially. And yet, actually encountering and working through diverse viewpoints, experiences, and perspectives is hard work. It’s uncomfortable. It’s emotionally exhausting. It can be downright frustrating.

Thus, given the opportunity, people typically revert to situations where they can be in homogeneous environments. They look for “safe spaces” and “culture fit.” And systems that are “personalized” are highly desirable. Most people aren’t looking to self-segregate, but they do it anyway. And, increasingly, the technologies and tools around us allow us to self-segregate with ease. Is your uncle annoying you with his political rants? Mute him. Tired of getting ads for irrelevant products? Reveal your preferences. Want your search engine to remember the things that matter to you? Let it capture data. Want to watch a TV show that appeals to your senses? Here are some recommendations.

Any company whose business model is based on advertising revenue and attention is incentivized to engage you by giving you what you want. And what you want in theory is different than what you want in practice.

Consider, for example, what Netflix encountered when it started its streaming offer. Users didn’t watch the movies that they had placed into their queue. Those movies were the movies they thought they wanted, movies that reflected their ideal self — 12 Years a Slave, for example. What they watched when they could stream whatever they were in the mood for at that moment was the equivalent of junk food — reruns of Friends, for example. (This completely undid Netflix’s recommendation infrastructure, which had been trained on people’s idealistic self-images.)

The divisions are not just happening through commercialism though. School choice has led people to self-segregate from childhood on up. The structures of American work life mean that fewer people work alongside others from different socioeconomic backgrounds. Our contemporary culture of retail and service labor means that there’s a huge cultural gap between workers and customers with little opportunity to truly get to know one another. Even many religious institutions are increasingly fragmented such that people have fewer interactions across diverse lines. (Just think about how there are now “family services” and “traditional services” which age-segregate.) In so many parts of public, civic, and professional life, we are self-segregating and the opportunities for doing so are increasing every day.

By and large, the American public wants to have strong connections across divisions. They see the value politically and socially. But they’re not going to work for it. And given the option, they’re going to renew their license remotely, try to get out of jury duty, and use available data to seek out housing and schools that are filled with people like them. This is the conundrum we now face.

Many pundits remarked that, during the 2016 election season, very few Americans were regularly exposed to people whose political ideology conflicted with their own. This is true. But it cannot be fixed by Facebook or news media. Exposing people to content that challenges their perspective doesn’t actually make them more empathetic to those values and perspectives. To the contrary, it polarizes them. What makes people willing to hear difference is knowing and trusting people whose worldview differs from their own. Exposure to content cannot make up for self-segregation.

If we want to develop a healthy democracy, we need a diverse and highly connected social fabric. This requires creating contexts in which the American public voluntarily struggles with the challenges of diversity to build bonds that will last a lifetime. We have been systematically undoing this, and the public has used new technological advances to make their lives easier by self-segregating. This has increased polarization, and we’re going to pay a heavy price for this going forward. Rather than focusing on what media enterprises can and should do, we need to focus instead on building new infrastructures for connection where people have a purpose for coming together across divisions. We need that social infrastructure just as much as we need bridges and roads.

This piece was originally published as part of a series on media, accountability, and the public sphere. See also:

- Hacking the Attention Economy by danah boyd

- What’s Propaganda Got To Do With It? by Caroline Jack

- Did Media Literacy Backfire? by danah boyd

- Are There Limits to Online Free Speech? by Alice Marwick

- How do you deal with a problem like “fake news?” by Robyn Caplan