A few weeks ago, Facebook’s data team released a set of data addressing a simple but complex question: How Diverse is Facebook? Given my own work over the last two years concerning the intersection of race/ethnicity/class and social network sites, I feel the need to respond. And, with pleasure, I’m going to respond by sharing a draft of a new paper.

A few weeks ago, Facebook’s data team released a set of data addressing a simple but complex question: How Diverse is Facebook? Given my own work over the last two years concerning the intersection of race/ethnicity/class and social network sites, I feel the need to respond. And, with pleasure, I’m going to respond by sharing a draft of a new paper.

But first, I want to begin by thanking the Facebook data team for actually making this data available for public dialogue. Far too few companies are willing to share their internal analyses, especially about topics that make people uncomfortable. I was disappointed that so many academics immediately began critiquing Facebook rather than appreciating the glimpse that we get into the data they get to see. So thank you Facebook data team!

There are many different ways to collect quantitative data involving categories like race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, etc. None of them are perfect. Even asking people to self-identify can be fraught, especially when someone is asked to place themselves into a box. Ask a self-identified queer boi to identity into the binaries of “female/male” and “gay/straight” and you’ll see nothing short of explosive anger. Race certainly isn’t any prettier, let alone ethnicity or class. The salience of these qualities also depends on what we’re trying to measure, what we’re trying to say. For example, if we’re talking about people who experience being targets of racism, should we concern ourselves more with self-identification or external labeling? At the coarsest level, we often assume race to boil down to skin color, meaning that we have to take into account how people read race, how they experience race, how they identify with race. We must always remember that race is a social construct and one’s experiences of race are shaped by how one perceives themselves in relation to others and how others perceive them. And the very notion of race differs across the globe.

Of course, this is bloody messy. And ethnicity and class are even harder to locate because self-identification isn’t always the best measure. Heck, while Americans have learned to self-identify with race (thanks to countless forms), we aren’t typically asked to self-identify with ethnicity or class. So these are pretty murky territories. As a result, scholars and demographers and marketers and many others have different ways of trying to measure these categories. None are perfect. We can debate endlessly about which is better but, personally, I think that does the conversation a disservice.

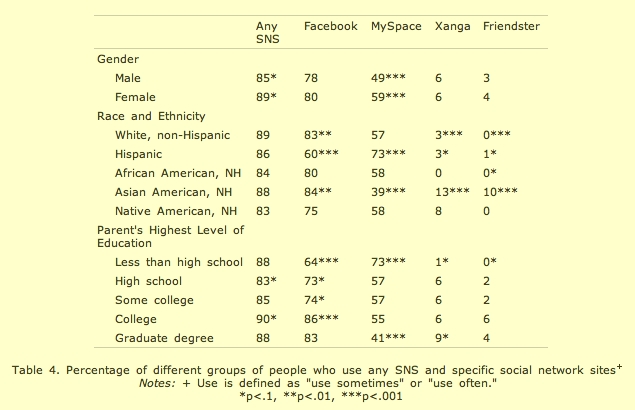

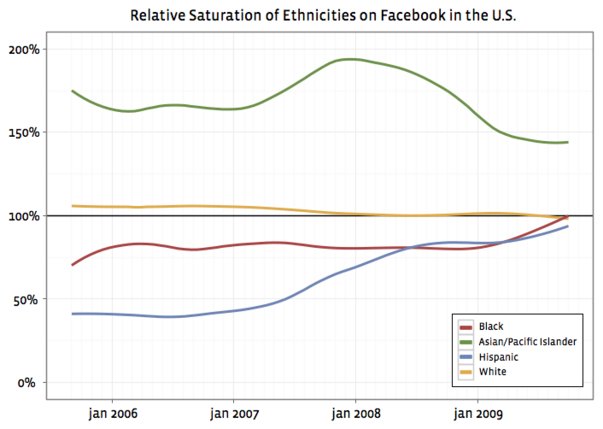

In trying to measure race (and, partially, ethnicity) of its users without having self-identification, Facebook decided to use a statistical technique known as mixture-modeling to make a best guess as to the racial makeup of its user base. They go to great lengths explaining what they did, but it is this graph that we should be attentive to:

This graph highlights that those American users most likely to be white were overrepresented on Facebook until last year while those most likely to be Asian have been overrepresented as far back as they are measuring. Yet, the two lines that should pique our interest are the blue and red lines, highlighting that those most likely to be black and Hispanic have been underrepresented until very recently. In other words, 2009 is the year in which Facebook went “mainstream” among all measured racial/ethnic groups in the U.S.

Folks keep asking me if this surprises me. It does not. This very much matches what I’m seeing in the field. (It also confirms what I was seeing in 2006-2007.) But it also doesn’t tell the whole story. Numbers never do. MySpace has definitely declined among young users in the U.S., especially in the last 12 months, but race – and ethnicity and socio-economic status – still inflect people’s experiences with these technologies. Just because Facebook has become broadly adopted does not mean that what everyone experiences on Facebook is the same. I would LOVE LOVE LOVE to see Facebook data that broke down app usage by demographic data (age, location, gender, and their measure of race). Given what I’m seeing in the field, I’d expect you’d see variation. I’d also expect to see variation in terms of how the service is accessed – via mobile, web, 3rd party APIs, etc. As young people tour me through their Facebook experience, I’m regularly reminded that different groups have wholly different experiences with the same service. As Facebook has become a platform, it is no longer reasonable to simply think about access. There’s also a different issue at play… perception. People perceive certain practices to be universal because “everyone they know” is doing it that way. One of the hardest parts of my job is to explain to people that what they are seeing, what they are experiencing, is not the same as what others are. Even if they’re using the same tools.

When the “digital divide” conversations started up, folks boiled down the discussion to being one of access. If only everyone had access, everything would be hunky dory. We’re closer to universal access today than ever before, but access is not bringing us the magical utopian panacea that we all dreamed of. Henry Jenkins has rightly pointed out that we see the emergence of a “participation gap” in that people’s participation is of different quantity and quality depending on many other factors. Social media takes all of this to a new level. It’s not just a question of what you get to experience with your access, but what you get to experience with your friend group with access. In other words, if you’re friends with 24/7 always-on geeks, what you’re experiencing with social media is very different than if you’re experiencing social media in a community where your friends all spend 12+ hours a day doing a form of labor that doesn’t allow access to internet technologies. Facebook’s data provides a glimpse into how Facebook access has become mainstream. It is the modern day portal. But I would argue that what people experience with this tool – and with the other social media assets they use – looks very different based on their experience.

Many folks think that I care about access. Don’t get me wrong – access is important. But I’m much more concerned about how racist and classist attitudes are shaping digital media, how technology reinforces inequality, and how our habit of assuming that everyone uses social media just like we do reinforces social divisions that we prefer to ignore. This issue became apparent to me when doing fieldwork because of the language that young people were using to differentiate MySpace and Facebook. Adoption differences alone were never the whole story. Ever since I released my controversial blog essay 2.5 years ago, I have been working to write up my data and analysis in a meaningful way. Doing so has not been easy. I’ve been very uncomfortable handling my own data, trying to treat it in a manner that is respectful of the teens that I interviewed and the dynamics that I witnessed. Thankfully, Lisa Nakamura and Peter Chow-White gave me the space to work out these issues. The fruit of my labor will be published in an upcoming Routledge anthology edited by them called Digital Race Anthology. With their permission, I am sharing with you a working draft of the article that I have struggled to produce:

In this article, I explore the themes I’ve been discussing for years but focus specifically on the language that young people used to differentiate MySpace and Facebook and how that language can be understood through the historical dynamics of segregation in the U.S. My decision to use the “white flight” frame is meant to be provocative, to encourage the reader to think about the rhetoric that we’re currently using and its parallels to earlier times. For example, how we employ “safety” as a way of marking turf and segmenting populations.

Given the conversations prompted by Facebook’s data, I felt the need to share this work-in-progress. Please feel free to comment or share your thoughts in whatever format makes sense to you.