(This post was written for Blogher and originally posted there.)

Every time I dare to talk about race or class and MySpace & Facebook in the same breath, a public explosion happens. This is the current state of things. Unfortunately, most folks who enter the fray prefer to reject the notion that race/class shape social media or that social media reflects bigoted attitudes than seriously address what’s at stake. Yet, look around. Twitter is flush with racist language in response to the active participation of blacks on the site. Comments on YouTube expose deep-seated bigotry in uncountable ways. The n-word is everyday vernacular in MMORPGs. In short, racism and classism permeates every genre of social media out there, reflecting the everyday attitudes of people that go well beyond social media. So why can’t we talk about it?

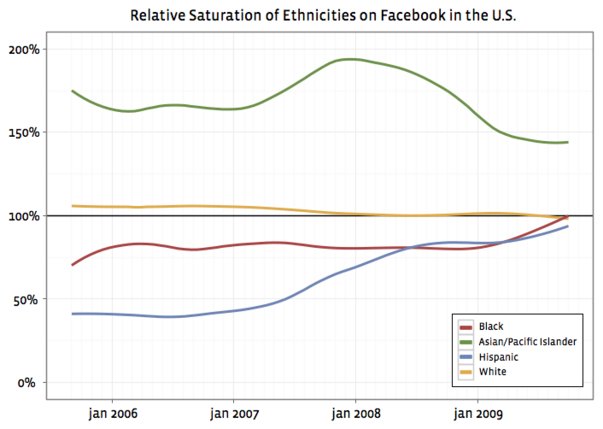

Let me back up and explain the context for this piece … three years ago, I wrote a controversial blog post highlighting the cultural division taking shape. Since then, I’ve worked diligently to try to make sense of what I first observed and ground it in empirical data. In 2009, I built on my analysis in “The Not-So-Hidden Politics of Class Online”, a talk I gave at the Personal Democracy Forum. Slowly, I worked to write an academic article called “White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with MySpace and Facebook” (to be published in a book called Digital Race Anthology, edited by Lisa Nakamura and Peter Chow-White). I published a draft of this article on my website in December. Then, on July 14, Christoper Mims posted a guest blog post at Technology Review entitled “Did Whites Flee the ‘Digital Ghetto’ of MySpace?” using my article as his hook. I’m not sure why Mims wrote this piece now or why he didn’t contact me, but so it goes.

Mims’ blog post prompted a new wave of discussion about whether or not there’s a race-based (or class-based) division between MySpace and Facebook today. My article does not address this topic. My article is a discussion of a phenomenon that happened from 2006-2007 using data collected during that period. The point of my article is not to discuss whether or not there was a division — quantitative data shows this better. My goal was to analyze American teenagers’ language when talking about Facebook and MySpace. The argument that I make is that the language used by teens has racialized overtones that harken back to the language used around “white flight.” In other words, what American teens are reflecting in their discussion of MySpace and Facebook shows just how deeply racial narratives are embedded in everyday life.

So, can we please dial the needle forward? Regardless of whether or not there’s still a race and class-based division in the U.S. between MySpace and Facebook, the language that people use to describe MySpace is still deeply racist and classist. Hell, we see that in the comments of every blog post that describes my analysis. And I’m sure we’ll get some here, since online forums somehow invite people to unapologetically make racist comments that they would never say aloud. And as much as those make me shudder, they’re also a reminder that the civil rights movement has a long way to go.

Race and class shape contemporary life in fundamental ways. People of color and the working poor live the experiences of racism and classism, but how this plays out is often not nearly as overt as it was in the 1960s. But that doesn’t mean that it has gone away.

There is still bigotry, and the divisions run deep in the U.S. We often talk about the Internet as the great equalizer, the space where we can be free of all of the weights of inequality. And yet, what we find online is often a reproduction of all of the issues present in everyday life. The Internet does not magically heal old wounds or repair broken bonds between people. More often, it shows just how deep those wounds go and how structurally broken many relationships are.

In this way, the Internet is often a mirror of the ugliest sides of our society, the aspects of our society that we so badly need to address. What the Internet does — for better or worse — is make visible aspects of society that have been delicately swept under the rug and ignored. We could keep on sweeping, or we could take the moment to rise up and develop new strategies for addressing the core issues that we’re seeing. Bigotry doesn’t go away by eliminating only what’s visible. It is eradicated by getting at the core underlying issues. What we’re seeing online allows us to see how much work there’s left to do.

In writing “White Flight in Networked Publics?”, I wanted to expose one aspect of how race and class shape how people see social media. My goal in doing so was to push back at the utopian rhetorics that frame the Internet as a kumbaya movement so that we can focus on addressing the major social issues that exist everywhere and are exposed in new ways via social media. When it comes to eradicating bigotry, I can’t say that I have the answers. But I know that we need to start a conversation. And my hope — from the moment that I first highlighted the divisions taking place in 2007 — is that we can use social media as both a lens into and a platform for discussing cultural inequality.

So how do we get started?

Photo credit: Moyix on Flickr