The below original text was the basis for Data & Society Founder and President danah boyd’s March 2018 SXSW Edu keynote,“What Hath We Wrought?” — Ed.

Growing up, I took certain truths to be self evident. Democracy is good. War is bad. And of course, all men are created equal.

My mother was a teacher who encouraged me to question everything. But I quickly learned that some questions were taboo. Is democracy inherently good? Is the military ethical? Does God exist?

I loved pushing people’s buttons with these philosophical questions, but they weren’t nearly as existentially destabilizing as the moments in my life in which my experiences didn’t line up with frames that were sacred cows in my community. Police were revered, so my boss didn’t believe me when I told him that cops were forcing me to give them free food, which is why there was food missing. Pastors were moral authorities and so our pastor’s infidelities were not to be discussed, at least not among us youth. Forgiveness is a beautiful thing, but hypocrisy is destabilizing. Nothing can radicalize someone more than feeling like you’re being lied to. Or when the world order you’ve adopted comes crumbling down.

The funny thing about education is that we ask our students to challenge their assumptions. And that process can be enlightening.

The funny thing about education is that we ask our students to challenge their assumptions. And that process can be enlightening. I will never forget being a teenager and reading “The People’s History of the United States.” The idea that there could be multiple histories, multiple truths blew my mind.Realizing that history is written by the winners shook me to my core. This is the power of education. But the hole that opens up, that invites people to look for new explanations…that hole can be filled in deeply problematic ways.When we ask students to challenge their sacred cows but don’t give them a new framework through which to make sense of the world, others are often there to do it for us.

For the last year, I’ve been struggling with media literacy. I have a deep level of respect for the primary goal. As Renee Hobbs has written, media literacy is the “active inquiry and critical thinking about the messages we receive and create.” The field talks about the development of competencies or skills to help people analyze, evaluate, and even create media. Media literacy is imagined to be empowering, enabling individuals to have agency and giving them the tools to help create a democratic society. But fundamentally, it is a form of critical thinking that asks people to doubt what they see. And that makes me nervous.

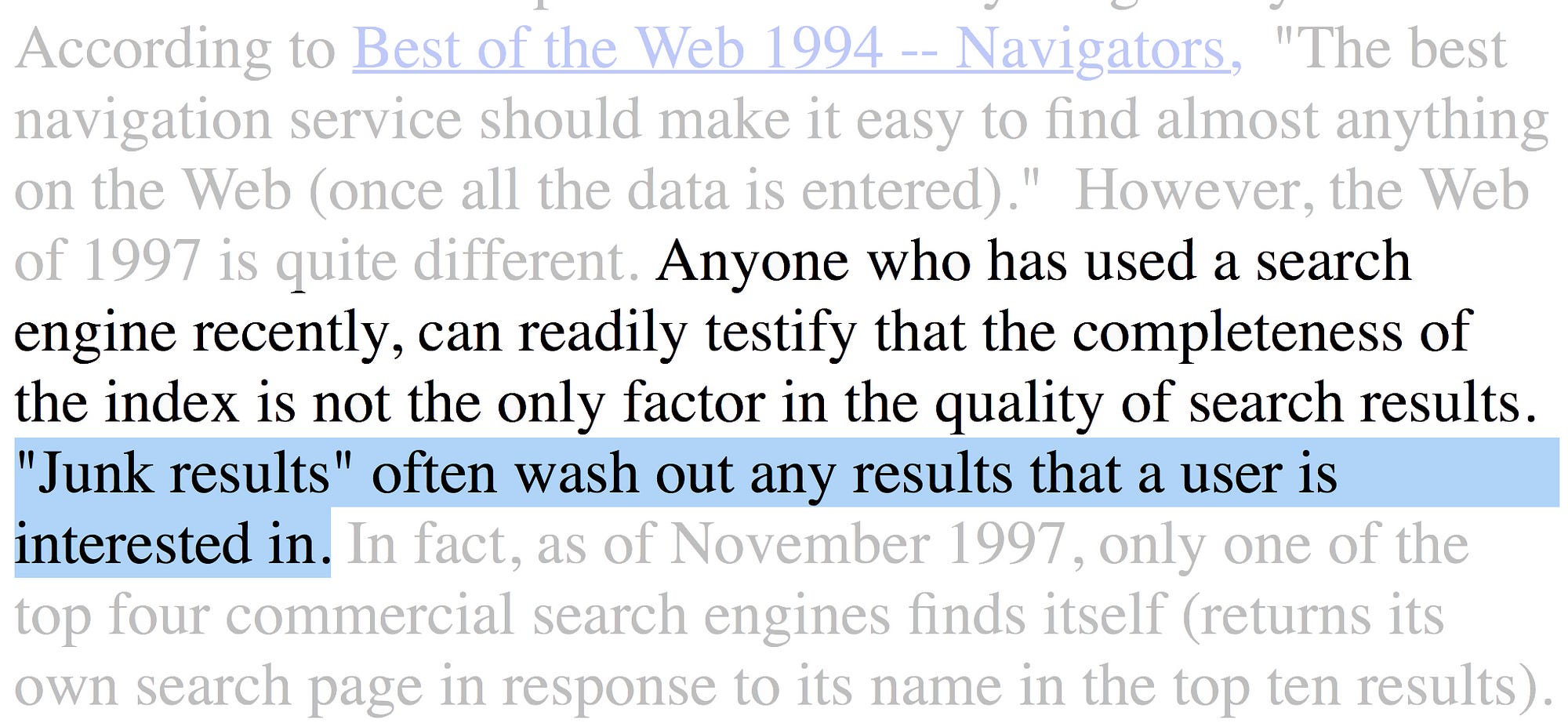

Most media literacy proponents tell me that media literacy doesn’t exist in schools. And it’s true that the ideal version that they’re aiming for definitely doesn’t. But I spent a decade in and out of all sorts of schools in the US, where I quickly learned that a perverted version of media literacy does already exist.Students are asked to distinguish between CNN and Fox. Or to identify bias in a news story. When tech is involved, it often comes in the form of “don’t trust Wikipedia; use Google.” We might collectively dismiss these practices as not-media-literacy, but these activities are often couched in those terms.

I’m painfully aware of this, in part because media literacy is regularly proposed as the “solution” to the so-called “fake news” problem. I hear this from funders and journalists, social media companies and elected officials. My colleagues Monica Bulger and Patrick Davison just released a report on media literacy in light of “fake news” given the gaps in current conversations. I don’t know what version of media literacy they’re imagining but I’m pretty certain it’s not the CNN vs Fox News version. Yet, when I drill in, they often argue for the need to combat propaganda, to get students to ask where the money is coming from, to ask who is writing the stories for what purposes, to know how to fact-check, etcetera. And when I push them further, I often hear decidedly liberal narratives. They talk about the Mercers or about InfoWars or about the Russians. They mock “alternative facts.” While I identify as a progressive, I am deeply concerned by how people understand these different conservative phenomena and what they see media literacy as solving.

I get that many progressive communities are panicked about conservative media, but we live in a polarized society and I worry about how people judge those they don’t understand or respect. It also seems to me that the narrow version of media literacy that I hear as the “solution” is supposed to magically solve our political divide. It won’t. More importantly, as I’m watching social media and news media get weaponized, I’m deeply concerned that the well-intended interventions I hear people propose will backfire, because I’m fairly certain that the crass versions of critical thinking already have.

My talk today is intended to interrogate some of the foundations upon which educating people about the media landscape depends. Rather than coming at this from the idealized perspective, I am trying to come at this from the perspective of where good intentions might go awry, especially in a moment in which narrow versions of media literacy and critical thinking are being proposed as the solution to major socio-cultural issues. I want to examine the instability of our current media ecosystem to then return to the question of:what kind of media literacy should we be working towards? So let’s dig in.

Epistemological Warfare

In 2017, sociologist Francesca Tripodi was trying to understand how conservative communities made sense of the seemingly contradictory words coming out of the mouth of the US President. Along her path, she encountered people talking about making sense of The Word when referencing his speeches. She began accompanying people in her study to their bible study groups. Then it clicked. Trained on critically interrogating biblical texts, evangelical conservative communities were not taking Trump’s messages as literal text. They were interpreting their meanings using the sameepistemological framework as they approached the bible. Metaphors and constructs matter more than the precision of words.

Why do we value precision in language? I sat down for breakfast with Gillian Tett, a Financial Times journalist and anthropologist. She told me that when she first moved to the States from the UK, she was confounded by our inability to talk about class. She was trying to make sense of what distinguished class in America. In her mind, it wasn’t race. Or education. It came down to what construction of language was respected and valued by whom. People became elite by mastering the language marked as elite. Academics, journalists, corporate executives, traditional politicians: they all master the art of communication. I did too. I will never forget being accused of speaking like an elite by my high school classmates when I returned home after a semester of college. More importantly, although it’s taboo in America to be explicitly condescending towards people on the basis of race or education, there’s no social cost among elites to mock someone for an inability to master language.For using terms like “shithole.”

Linguistic and communications skills are not universally valued. Those who do not define themselves through this skill loathe hearing the never-ending parade of rich and powerful people suggesting that they’re stupid, backwards, and otherwise lesser. Embracing being anti-PC has become a source of pride, a tactic of resistance. Anger boils over as people who reject “the establishment” are happy to watch the elites quiver over their institutions being dismantled. This is why this is a culture war. Everyone believes they are part of the resistance.

But what’s at the root of this cultural war? Cory Doctorow got me thinkingwhen he wrote the following:

We’re not living through a crisis about what is true, we’re living through a crisis about how we know whether something is true. We’re not disagreeing about facts,we’re disagreeing about epistemology. The “establishment” version of epistemology is, “We use evidence to arrive at the truth, vetted by independent verification (but trust us when we tell you that it’s all been independently verified by people who were properly skeptical and not the bosom buddies of the people they were supposed to be fact-checking).”

The “alternative facts” epistemological method goes like this: “The ‘independent’ experts who were supposed to be verifying the ‘evidence-based’ truth were actually in bed with the people they were supposed to be fact-checking. In the end, it’s all a matter of faith, then: you either have faith that ‘their’ experts are being truthful, or you have faith that we are. Ask your gut, what version feels more truthful?”

Let’s be honest — most of us educators are deeply committed to a way of knowing that is rooted in evidence, reason, and fact. But who gets to decide what constitutes a fact? In philosophy circles, social constructivists challenge basic tenets like fact, truth, reason, and evidence. Yet, it doesn’t take a doctorate of philosophy to challenge the dominant way of constructing knowledge. Heck, 75 years ago, evidence suggesting black people were biologically inferior was regularly used to justify discrimination. And this was called science!

In many Native communities, experience trumps Western science as the key to knowledge. These communities have a different way of understanding topics like weather or climate or medicine. Experience is also used in activist circles as a way of seeking truth and challenging the status quo. Experience-based epistemologies also rely on evidence, but not the kind of evidence that would be recognized or accepted by those in Western scientific communities.

Those whose worldview is rooted in religious faith, particularly Abrahamic religions, draw on different types of information to construct knowledge. Resolving scientific knowledge and faith-based knowledge has never been easy; this tension has countless political and social ramifications. As a result, American society has long danced around this yawning gulf and tried to find solutions that can appease everyone. But you can’t resolve fundamental epistemological differences through compromise.

No matter what worldview or way of knowing someone holds dear, they always believe that they are engaging in critical thinking when developing a sense of what is right and wrong, true and false, honest and deceptive. But much of what they conclude may be more rooted in their way of knowing than any specific source of information.

If we’re not careful, “media literacy” and “critical thinking”will simply be deployed as an assertion of authority over epistemology.

Right now, the conversation around fact-checking has already devolved to suggest that there’s only one truth. And we have to recognize that there are plenty of students who are taught that there’s only one legitimate way of knowing, one accepted worldview. This is particularly dicey at the collegiate level, where us professors have been taught nothing about how to teach across epistemologies.

Personally, it took me a long time to recognize the limits of my teachers. Like many Americans in less-than-ideal classrooms, I was taught that history was a set of facts to be memorized. When I questioned those facts, I was sent to the principal’s office for disruption. Frustrated and confused, I thought that I was being force-fed information for someone else’s agenda. Now I can recognize that that teacher was simply exhausted, underpaid, and waiting for retirement. But it took me a long time to realize that there was value in history and that history is a powerful tool.

Weaponizing Critical Thinking

The political scientist Deen Freelon was trying to make sense of the role of critical thinking to address “fake news.” He ended up looking back at a fascinating campaign by Russian Today (known as RT). Their motto for a while was “question more.” They produced a series of advertisements as teasers for their channel. These advertisements were promptly banned in the US and UK, resulting in RT putting up additional ads about how they were banned and getting tremendous mainstream media coverage about being banned. What was so controversial? Here’s an example:

“Just how reliable is the evidence that suggests human activity impacts on climate change? The answer isn’t always clear-cut. And it’s only possible to make a balanced judgement if you are better informed. By challenging the accepted view, we reveal a side of the news that you wouldn’t normally see. Because we believe that the more you question, the more you know.”

If you don’t start from a place where you’re confident that climate change is real, this sounds quite reasonable. Why wouldn’t you want more information? Why shouldn’t you be engaged in critical thinking? Isn’t this what you’re encouraged to do at school? So why is asking this so taboo? And lest you think that this is a moment to be condescending towards climate deniers, let me offer another one of their ads.

“Is terror only committed by terrorists? The answer isn’t always clear-cut. And it’s only possible to make a balanced judgement if you are better informed. By challenging the accepted view, we reveal a side of the news that you wouldn’t normally see. Because we believe that the more you question, the more you know.”

Many progressive activists ask whether or not the US government commits terrorism in other countries. The ads all came down because they were too political, but RT got what they wanted: an effective ad campaign. They didn’t come across as conservative or liberal, but rather a media entity that was “censored” for asking questions. Furthermore, by covering the fact that they were banned, major news media legitimized their frame under the rubric of “free speech.” Under the assumption that everyone should have the right to know and to decide for themselves.

We live in a world now where we equate free speech with the right to be amplified. Does everyone have the right to be amplified? Social media gave us that infrastructure under the false imagination that if we were all gathered in one place, we’d find common ground and eliminate conflict. We’ve seen this logic before. After World War II, the world thought that connecting the globe through financial interdependence would prevent World War III. It’s not clear that this logic will hold.

For better and worse, by connecting the world through social media and allowing anyone to be amplified, information can spread at record speed.There is no true curation or editorial control. The onus is on the public to interpret what they see. To self-investigate. Since we live in a neoliberal society that prioritizes individual agency, we double down on media literacy as the “solution” to misinformation. It’s up to each of us as individuals to decide for ourselves whether or not what we’re getting is true.

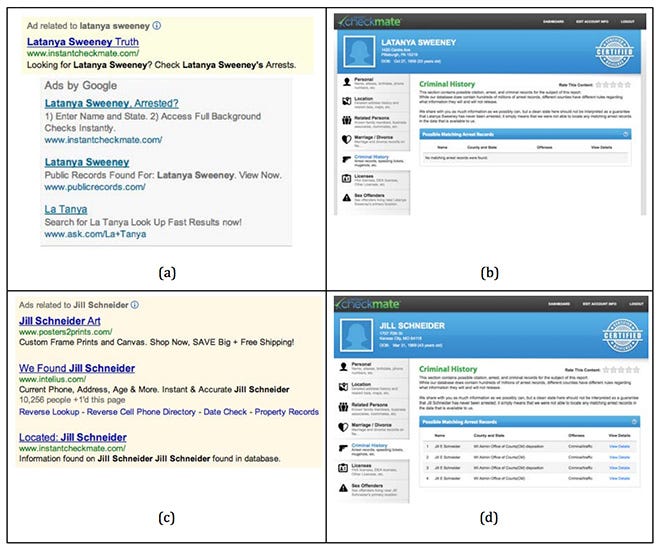

Yet, if you talk with someone who has posted clear, unquestionable misinformation, more often than not, they know it’s bullshit. Or they don’t care whether or not it’s true. Why do they post it then? Because they’re making a statement. The people who posted this meme (figure 1) didn’t bother to fact check this claim. They didn’t care. What they wanted to signal loud and clear is that they hated Hillary Clinton. And that message was indeed heard loud and clear. As a result, they are very offended if you tell them that they’ve been duped by Russians into spreading propaganda. They don’t believe you for one second.

Misinformation is contextual. Most people believe that people they know are gullible to false information, but that they themselves are equipped to separate the wheat from the chaff. There’s widespread sentiment that we can fact check and moderate our way out of this conundrum. This will fail. Don’t forget that for many people in this country, both education and the media are seen as the enemy — two institutions who are trying to have power over how people think. Two institutions that are trying to assert authority over epistemology.

Finding the Red Pill

Growing up on Usenet, Godwin’s Law was more than an adage to me. I spent countless nights lured into conversation by the idea that someone was wrong on the internet. And I long ago lost count about how many of them ended up with someone invoking Hitler or the Holocaust. I might have even been to blame in some of these conversations.

Fast forward 15 years to the point when Nathan Poe wrote a poignant comment on an online forum dedicated to Christianity: “Without a winking smiley or other blatant display of humor, it is utterly impossible to parody a Creationist in such a way that someone won’t mistake for the genuine article.”Poe’s Law, as it became known, signals that it’s hard to tell the difference between an extreme view and a parody of an extreme view on the internet.

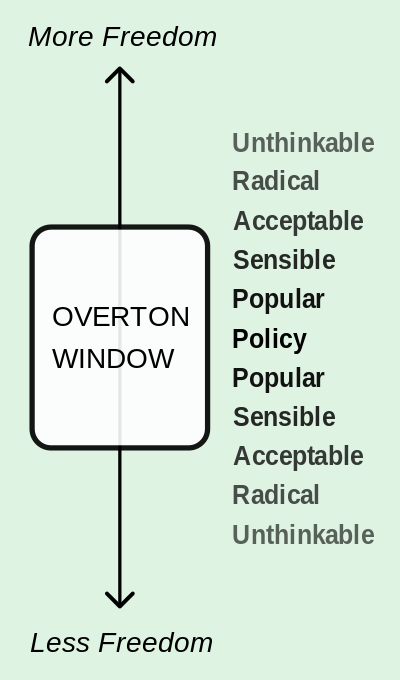

In their book, “The Ambivalent Internet,”media studies scholars Whitney Phillips and Ryan Milner highlight how a segment of society has become so well-versed at digital communications — memes, GIFs, videos, etc. — that they can use these tools of expression to fundamentally destabilize others’communication structures and worldviews. It’s hard to tell what’s real and what’s fiction, what’s cruel and what’s a joke. But that’s the point. That is howirony and ambiguity can be weaponized. And for some, the goal is simple:dismantle the very foundations of elite epistemological structures that are so deeply rooted in fact and evidence.

Many people, especially young people, turn to online communities to make sense of the world around them. They want to ask uncomfortable questions, interrogate assumptions, and poke holes at things they’ve heard. Welcome to youth. There are some questions that are unacceptable to ask in public and they’ve learned that. But in many online fora, no question or intellectual exploration is seen as unacceptable. To restrict the freedom of thought is to censor. And so all sorts of communities have popped up for people to explore questions of race and gender and other topics in the most extreme ways possible. And these communities have become slippery. Are those taking on such hateful views real? Or are they being ironic?

In the 1999 film The Matrix, Morpheus says to Neo: “You take the blue pill,the story ends. You wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want. You take the red pill, you stay in Wonderland, and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes.” Most youth aren’t interested in having the wool pulled over their head, even if blind faith might be a very calming way of living. Restricted in mobility and stressed to holy hell, they want to have access to what’s inaccessible, know what’s taboo, and say what’s politically incorrect. So who wouldn’t want to take the red pill?

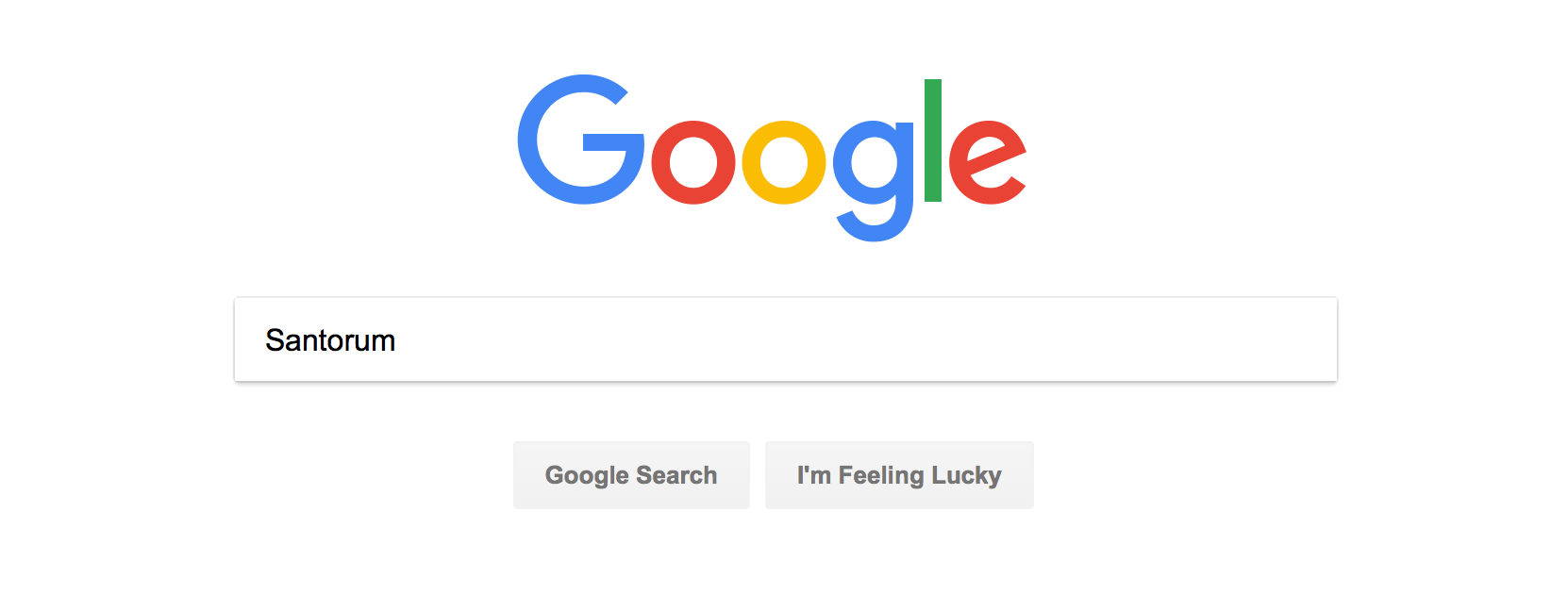

In some online communities, taking the red pill refers to the idea of waking up to how education and media are designed to deceive you into progressive propaganda. In these environments, visitors are asked to question more. They’re invited to rid themselves of their politically correct shackles. There’s an entire online university designed to undo accepted ideas about diversity, climate, and history. Some communities are even more extreme in their agenda. These are all meant to fill in the gaps for those who are opening to questioning what they’ve been taught.

In 2012, it was hard not to avoid the names Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman, but that didn’t mean that most people understood the storyline.In South Carolina, a white teenager who wasn’t interested in the news felt like he needed to know what the fuss was all about. He decided to go to Wikipedia to understand more. He was left with the impression that Zimmerman was clearly in the right and disgusted that everyone was defending Martin. While reading up on this case, he ran across the term “black on white crime” on Wikipedia and decided to throw that term into Google where he encountered a deeply racist website inviting him to wake up to a reality that he had never considered. He took that red pill and dove deep into a worldview whose theory of power positioned white people as victims. Over a matter of years, he began to embrace those views, to be radicalized towards extreme thinking. On June 17, 2015, he sat down for an hour with a group of African-American church-goers in Charleston South Carolina before opening fire on them, killing 9 and injuring 1. His goal was simple: he wanted to start a race war.

It’s easy to say that this domestic terrorist was insane or irrational, but he began his exploration trying to critically interrogate the media coverage of a story he didn’t understand. That led him to online fora filled with people who have spent decades working to indoctrinate people into a deeply troubling, racist worldview. They draw on countless amounts of “evidence,” engage in deeply persuasive discursive practices, and have the mechanisms to challenge countless assumptions. The difference between what is deemed missionary work, education, and radicalization depends a lot on your worldview. And your understanding of power.

Who Do You Trust?

The majority of Americans do not trust the news media. There are many explanations for this — loss of local news, financial incentives, hard to distinguish between opinion and reporting, etc. But what does it mean to encourage people to be critical of the media’s narratives when they are already predisposed against the news media?

Perhaps you want to encourage people to think critically about how information is constructed, who is paying for it, and what is being left out. Yet, among those whose prior is to not trust a news media institution, among those who see CNN and The New York Times as “fake news,” they’re already there. They’re looking for flaws. It’s not hard to find them. After all, the news industry is made of people in institutions in a society. So when youth are encouraged to be critical of the news media, they come away thinking that the media is lying. Depending on someone’s prior, they may even take what they learn to be proof that the media is in on the conspiracy. That’s where things get very dicey.

Many of my digital media and learning colleagues encourage people to make media to help understand how information is produced. Realistically, many young people have learned these skills outside the classroom as they seek to represent themselves on Instagram, get their friends excited about a meme, or gain followers on YouTube. Many are quite skilled at using media, but to what end? Every day, I watch teenagers produce anti-Semitic and misogynistic content using the same tools that activists use to combat prejudice. It’s notable that many of those who are espousing extreme viewpoints are extraordinarily skilled at using media. Today’s neo-Nazis are a digital propaganda machine. Developing media making skills doesn’t guarantee that someone will use them for good. This is the hard part.

Most of my peers think that if more people are skilled and more people are asking hard questions, goodness will see the light. In talking about misunderstandings of the First Amendment, Nabiha Syed of Buzzfeedhighlights that the frame of the “marketplace of ideas” sounds great, but is extremely naive. Doubling down on investing in individuals as a solution to a systemic abuse of power is very American. But the best ideas don’t always surface to the top. Nervously, many of us tracking manipulation of media are starting to think that adversarial messages are far more likely to surface than well-intended ones.

This is not to say that we shouldn’t try to educate people. Or that producing critical thinkers is inherently a bad thing. I don’t want a world full of sheeple.But I also don’t want to naively assume what media literacy could do in responding to a culture war that is already underway. I want us to grapple with reality, not just the ideals that we imagine we could maybe one day build.

It’s one thing to talk about interrogating assumptions when a person can keep emotional distance from the object of study. It’s an entirely different thing to talk about these issues when the very act of asking questions is what’s being weaponized. This isn’t historical propaganda distributed through mass media. Or an exercise in understanding state power. This is about making sense of an information landscape where the very tools that people use to make sense of the world around them have been strategically perverted by other people who believe themselves to be resisting the same powerful actors that we normally seek to critique.

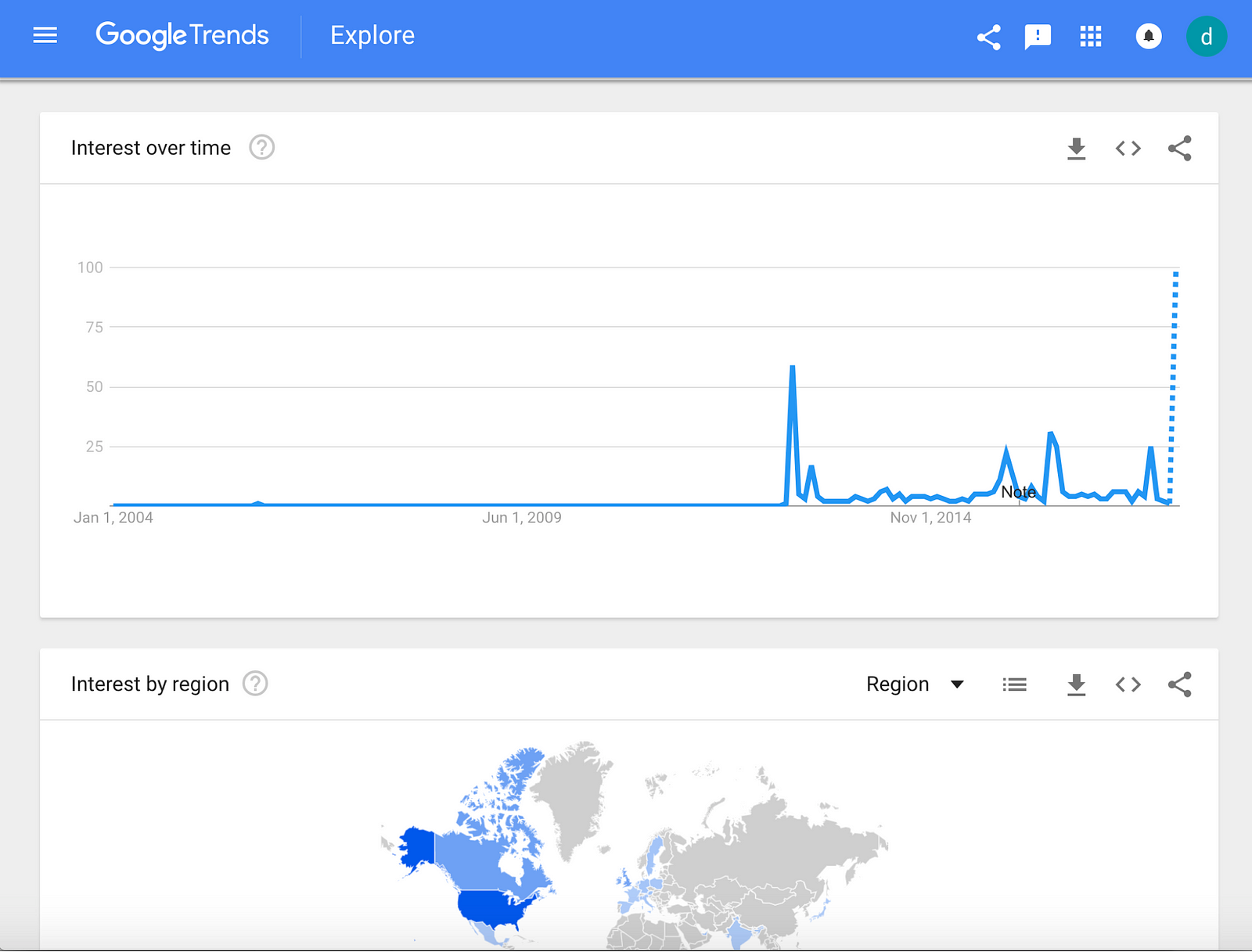

Take a look at the graph above. Can you guess what search term this is? This is the search query for “crisis actors.” This concept emerged as a conspiracy theory after Sandy Hook. Online communities worked hard to get this to land with the major news media after each shooting. With Parkland, they finally succeeded. Every major news outlet is now talking about crisis actors, as though it’s a real thing, or something to be debunked. When teenage witnesses of the mass shooting in Parkland speak to journalists these days, they have to now say that they are not crisis actors. They must negate a conspiracy theory that was created to dismiss them. A conspiracy theory that undermines their message from the get-go. And because of this, many people have turned to Google and Bing to ask what a crisis actor is. They quickly get to the Snopes page. Snopes provides a clear explanation of why this is a conspiracy. But you are now asked to not think of an elephant.

You may just dismiss this as craziness, but getting this narrative into the media was designed to help radicalize more people. Some number of people will keep researching, trying to understand what the fuss is all about. They’ll find online fora discussing the images of a brunette woman and ask themselves if it might be the same person. They will try to understand the fight between David Hogg and Infowars or question why Infowars is being restricted by YouTube. They may think this is censorship. Seeds of doubt will start to form. And they’ll ask whether or not any of the articulate people they see on TV might actually be crisis actors. That’s the power of weaponized narratives.

One of the main goals for those who are trying to manipulate media is to pervert the public’s thinking. It’s called gaslighting. Do you trust what is real?One of the best ways to gaslight the public is to troll the media. By getting the news media to be forced into negating frames, they can rely on the fact that people who distrust the media often respond by self-investigating. This is the power of the boomerang effect. And it has a history. After all, the CDC realized that the more news media negated the connection between autism and vaccination, the more the public believed there was something real there.

In 2016, I watched networks of online participants test this theory through an incident now known as Pizzagate. They worked hard to get the news media to negate the conspiracy theory, believing that this would prompt more people to try to research if there was something real there. They were effective. The news media covered the story to negate it. Lots of people decided to self-investigate. One guy even showed up with a gun.

The term “gaslighting” originates in the context of domestic violence. The term refers back to an 1944 movie called Gas Light where a woman is manipulated by her husband in a way that leaves her thinking she’s crazy. It’sa very effective technique of control. It makes someone submissive and disoriented, unable to respond to a relationship productively. While many anti-domestic violence activists argue that the first step is to understand that gaslighting exists, the “solution” is not to fight back against the person doing the gaslighting. Instead, it’s to get out. Furthermore, anti-domestic violence experts argue that recovery from gaslighting is a long and arduous process, requiring therapy. They recognize that once instilled, self-doubt is hard to overcome.

While we have many problems in our media landscape, the most dangerous is how it is being weaponized to gaslight people.

And unlike the domestic violence context, there is no “getting out” that is really possible in a media ecosystem. Sure, we can talk about going off the grid and opting out of social media and news media, but c’mon now.

The Cost of Triggering

In 2017, Netflix released a show called 13 Reasons Why. Before parents and educators had even heard of the darn show, millions of teenagers had watched it. For most viewers, it was a fascinating show. The storyline was enticing, the acting was phenomenal. But I’m on the board of Crisis Text Line, an amazing service where people around this country talk with trained counselors via text message when they’re in a crisis. Before the news media even began talking about the show, we started to see the impact. After all, the premise of the show is that a teen girl died by suicide and left behind 13 tapes explaining how people had bullied her to justify her decision.

At Crisis Text Line, we do active rescues every night. This means that we send emergency personnel to the homes of someone who is in the middle of a suicide attempt in an effort to save their lives. Sometimes, we succeed. Sometimes, we don’t. It’s heartbreaking work. As word of 13 Reasons Why got out and people started watching the show, our numbers went through the roof. We were drowning in young people referencing the show, signaling how it had given them a framework for ending their lives. We panicked. All hands on deck. As we got things under control, I got angry. What the hell was Netflix thinking?

Researchers know the data on suicide and media. The more the media normalizes suicide, the more suicide is put into people’s head as a possibility,the more people who are on the edge start to take it seriously and consider it for themselves. After early media effects research was published, journalists developed best practices to minimize their coverage of suicide. As Joan Donovan often discusses, this form of “strategic silence” was viable in earlier media landscapes; it’s a lot harder now. Today, journalists and media makers feel as though the fact that anyone could talk about suicide on the internet means that they should have a right to do so too.

We know that you can’t combat depression through rational discourse.Addressing depression is hard work. And I’m deeply concerned that we don’t have the foggiest clue how to approach the media landscape today. I’m confident that giving grounded people tools to think smarter can be effective.But I’m not convinced that we know how to educate people who do not share our epistemological frame. I’m not convinced that we know how to undo gaslighting. I’m not convinced that we understand how engaging people about the media intersects with those struggling with mental health issues.And I’m not convinced that we’ve even begun to think about the unintended consequences of our good — let alone naive — intentions.

In other words, I think that there are a lot of assumptions baked into how we approach educating people about sensitive issues and our current media crisis has made those painfully visible.

Oh, and by the way, the Netflix TV show ends by setting up Season 2 to start with a school shooting. WTF, Netflix?

Pulling Back Out

So what role do educators play in grappling with the contemporary media landscape? What kind of media literacy makes sense? To be honest, I don’t know. But it’s unfair to end a talk like this without offering some path forward so I’m going to make an educated guess.

I believe that we need to develop antibodies to help people not be deceived.

That’s really tricky because most people like to follow their gut more than than their mind. No one wants to hear that they’re being tricked. Still, I thinkthere might be some value in helping people understand their own psychology.

Consider the power of nightly news and talk radio personalities. If you bring Sean Hannity, Rachel Maddow, or any other host into your home every night,you start to appreciate how they think. You may not agree with them, but youbuild a cognitive model of their words such that they have a coherent logic to them. They become real to you, even if they don’t know who you are. This is what scholars call “parasocial interaction.” And the funny thing about humanpsychology is that we trust people who we invest our energies into understanding. That’s why bridging difference requires humanizing people across viewpoints.

Empathy is a powerful emotion, one that most educators want to encourage.But when you start to empathize with worldviews that are toxic, it’s very hard to stay grounded. It requires deep cognitive strength. Scholars who spend a lot of time trying to understand dangerous worldviews work hard to keep their emotional distance. One very basic tactic is to separate the different signals. Just read the text rather than consume the multimedia presentation of that. Narrow the scope. Actively taking things out of context can be helpful for analysis precisely because it creates a cognitive disconnect. This is the opposite of how most people encourage everyday analysis of media, where the goal is to appreciate the context first. Of course, the trick here is wanting to keep that emotional distance. Most people aren’t looking for that.

I also believe that it’s important to help students truly appreciate epistemological differences. In other words, why do people from different worldviews interpret the same piece of content differently? Rather than thinking about the intention behind the production, let’s analyze the contradictions in the interpretation. This requires developing a strong sense of how others think and where the differences in perspective lie. From an educational point of view, this means building the capacity to truly hear and embrace someone else’s perspective and teaching people to understand another’s view while also holding their view firm. It’s hard work, an extension of empathy into a practice that is common among ethnographers. It’s also a skill that is honed in many debate clubs. The goal is to understand the multiple ways of making sense of the world and use that to interpret media.Of course, appreciating the view of someone who is deeply toxic isn’t always psychologically stabilizing.

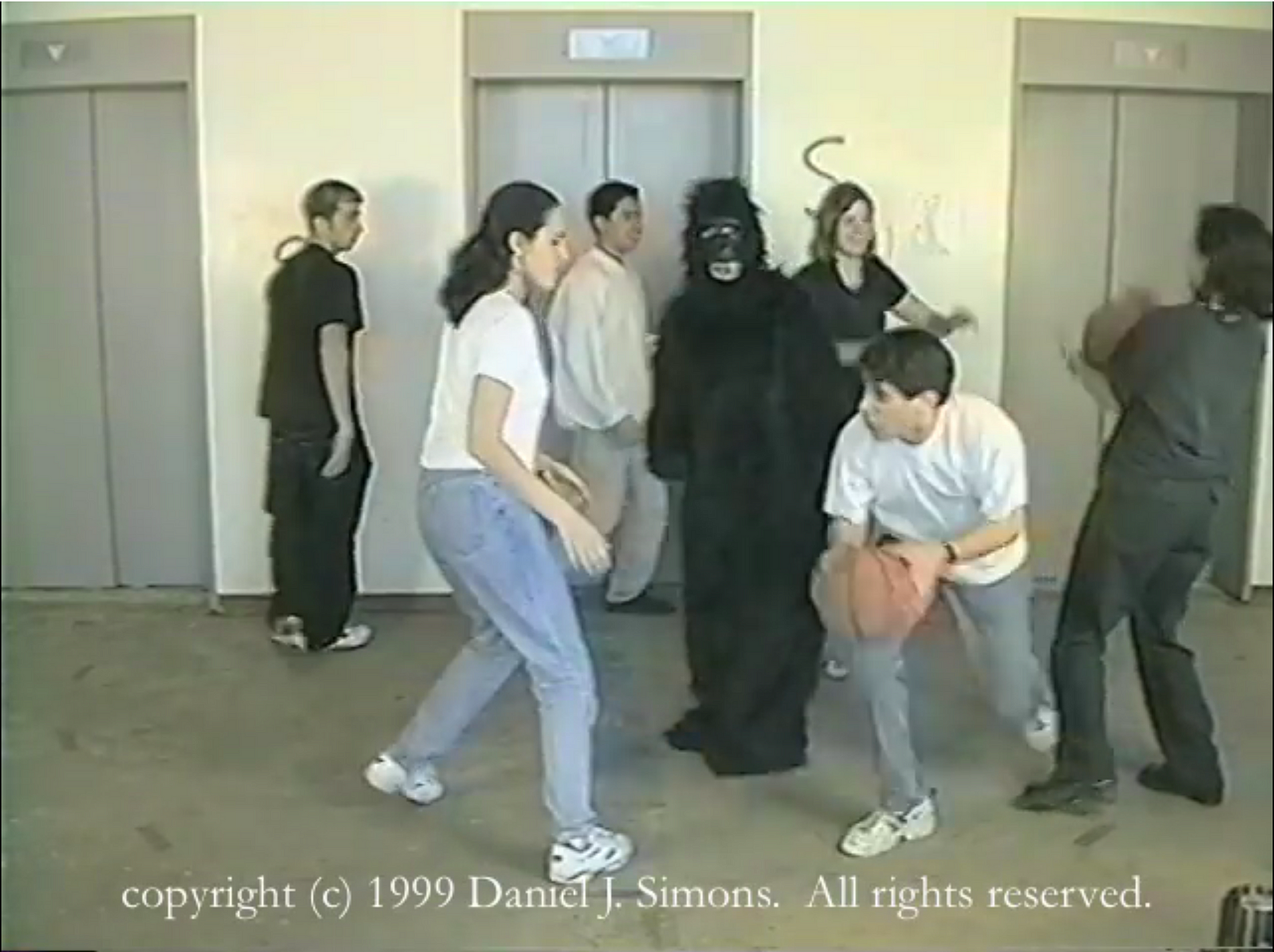

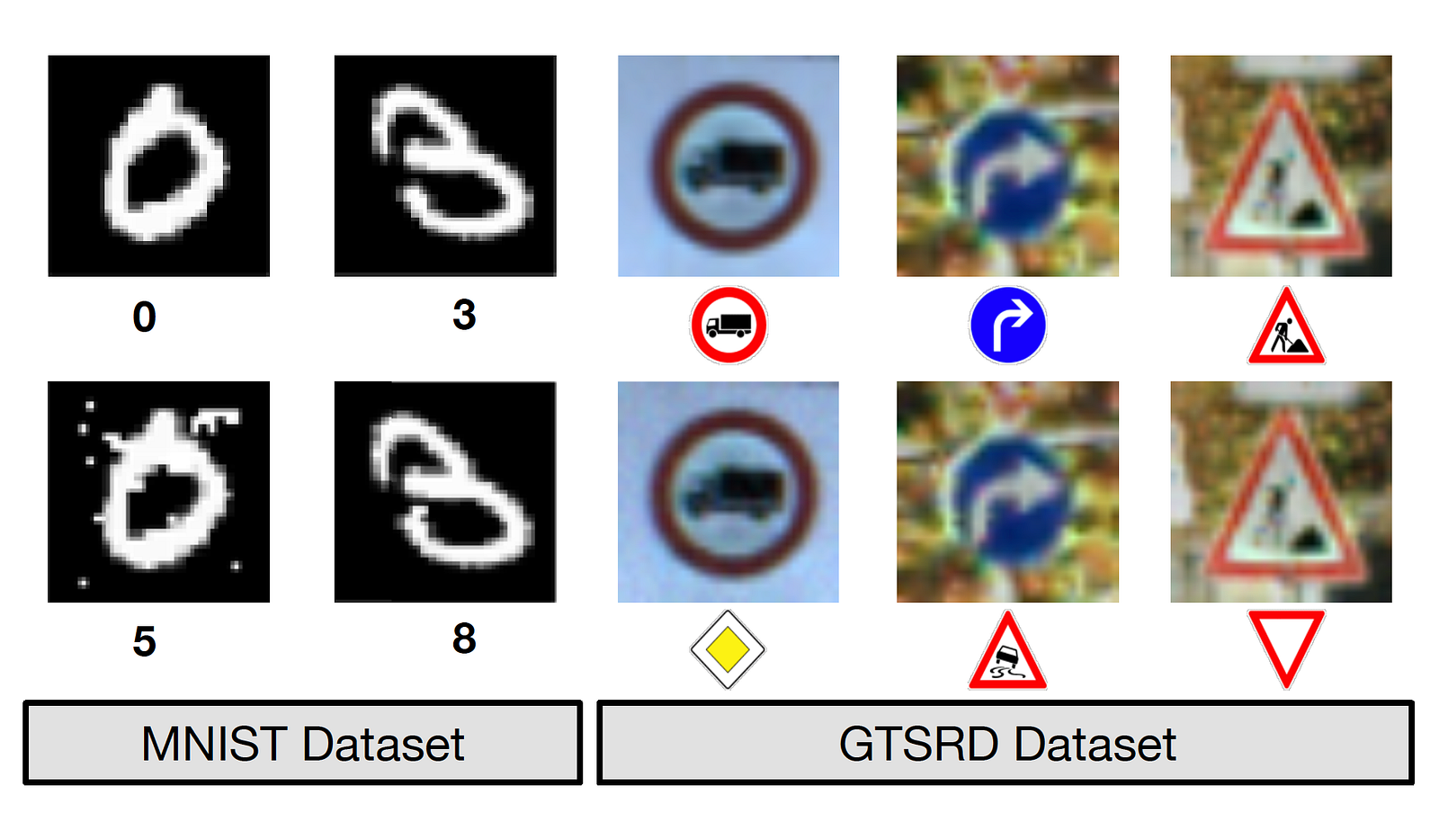

Another thing I recommend is to help students see how they fill in gaps when the information presented to them is sparse and how hard it is to overcome priors. Conversations about confirmation bias are important here because it’s important to understand what information we accept and what information we reject. Selective attention is another tool, most famously shown to students through the “gorilla experiment.” If you aren’t familiar with this experiment, it involves showing a basketball video and focusing on counting passes made by people in one color shirt and then asking if they saw the gorilla. Many people do not. Inverting these cognitive science exercises,asking students to consider different fan fiction that fills in the gaps of a story with divergent explanations is another way to train someone to recognize how their brain fills in gaps.

What’s common about the different approaches I’m suggesting is that they are designed to be cognitive strengthening exercises, to help students recognize their own fault lines, not the fault lines of the media landscape around them. I can imagine that this too could be called media literacy and if you want to bend your definition that way, I’ll accept it. But the key is to realize the humanity in ourselves and in others. We cannot and should not assert authority over epistemology, but we can encourage our students to be more aware of how interpretation is socially constructed. And to understand how that can be manipulated. Of course, just because you know you’re being manipulated doesn’t mean that you can resist it. And that’s where my proposal starts to get shaky.

Let’s be honest — our information landscape is going to get more and more complex. Educators have a critical role to play in helping individuals and societies navigate what we encounter. But the path forward isn’t about doubling down on what constitutes a fact or teaching people to assess sources.Rebuilding trust in institutions and information intermediaries is important, but we can’t assume the answer is teaching students to rely on those signals.The first wave of media literacy was responding to propaganda in a mass media context. We live in a world of networks now. We need to understand how those networks are intertwined and how information that spreads through dyadic — even if asymmetric — encounters is understood and experienced differently than that which is produced and disseminated through mass media.

Above all, we need to recognize that information can, is, and will be weaponized in new ways. Today’s propagandist messages are no longer simply created by Madison Avenue or Edward Bernays-style State campaigns. For the last 15 years, a cohort of young people has learned how to hack the attention economy in an effort to have power and status in this new information ecosystem. These aren’t just any youth. They are young people who are disenfranchised, who feel as though the information they’re getting isn’t fulfilling, who struggle to feel powerful. They are trying to make sense of an unstable world and trying to respond to it in a way that is personally fulfilling.Most youth are engaged in invigorating activities. Others are doing the same things youth have always done. But there are youth out there who feel alienated and disenfranchised, who distrust the system and want to see it all come down. Sometimes, this frustration leads to productive ends. Often it does not. But until we start understanding their response to our media society, we will not be able to produce responsible interventions. So I would argue that we need to start developing a networked response to this networked landscape. And it starts by understanding different ways of constructing knowledge.

Special thanks to Monica Bulger, Mimi Ito, Whitney Phillips, Cathy Davidson, Sam Hinds Garcia, Frank Shaw, and Alondra Nelson for feedback.

Update (March 16, 2018): I crafted some responses to the most common criticisms I’ve received to date about this work here. (Also, the original version of this blog post was published on Medium.)

I was 19 years old when a some configuration of anonymous people came after me. They got access to my email and shared some of the most sensitive messages on an anonymous forum. This was after some of my girl friends received anonymous voice messages describing how they would be raped. And after the black and Latinx high school students I was mentoring were subject to targeted racist messages whenever they logged into the computer cluster we were all using. I was ostracized for raising all of this to the computer science department’s administration. A year later, when I applied for an internship at Sun Microsystems, an alum known for his connection to the anonymous server that was used actually said to me, “I thought that they managed to force you out of CS by now.”

I was 19 years old when a some configuration of anonymous people came after me. They got access to my email and shared some of the most sensitive messages on an anonymous forum. This was after some of my girl friends received anonymous voice messages describing how they would be raped. And after the black and Latinx high school students I was mentoring were subject to targeted racist messages whenever they logged into the computer cluster we were all using. I was ostracized for raising all of this to the computer science department’s administration. A year later, when I applied for an internship at Sun Microsystems, an alum known for his connection to the anonymous server that was used actually said to me, “I thought that they managed to force you out of CS by now.”