On July 25th, I was asked to address thousands of women (and some men) at the 10th annual Blogher conference. I was asked to reflect on what it meant to be a blogger and so I did. You can watch it here:

Or you can read an edited version of the remarks I offered below

I started blogging in 1997. I was 19 years old. I didn’t call it blogging then, and my blog didn’t look like it does now. It was a manually-created HTML site with a calendar made of tables (OMG tables) and Geocities-style forward and back buttons with terrible graphics. I posted entries a few times a week as part of an independent study on Buddhism as a Brown University student that involved both meditation and self-reflection. Each week, the monk I was working with would ask me to reflect on certain things, and I would write. And write. And write. He lived in Ohio and had originally proposed sending letters, but I thought pencils were a foreign concept. I decided to type my thoughts and that, if I was going to type them, I might as well put them up online. Ah, teen logic.

I started blogging in 1997. I was 19 years old. I didn’t call it blogging then, and my blog didn’t look like it does now. It was a manually-created HTML site with a calendar made of tables (OMG tables) and Geocities-style forward and back buttons with terrible graphics. I posted entries a few times a week as part of an independent study on Buddhism as a Brown University student that involved both meditation and self-reflection. Each week, the monk I was working with would ask me to reflect on certain things, and I would write. And write. And write. He lived in Ohio and had originally proposed sending letters, but I thought pencils were a foreign concept. I decided to type my thoughts and that, if I was going to type them, I might as well put them up online. Ah, teen logic.

Most of those early reflections were deeply intense. I posted in detail about what it meant to navigate rape and abuse, to come into a sense of self in light of scarring situations. I have since deleted much of this material, not because I’m ashamed by it, but because I found that it created the wrong introduction. As my blog became more professional, people would flip back and look at those first posts and be like errr… uhh… While I’m completely open about my past, I’ve found that rape details are not the way that I want to start a conversation most of the time. So, in a heretical act, I deleted those posts.

What my blog is to me and to others has shifted tremendously over the years. For the first five years, my blog was read by roughly four people. That was fine because I wasn’t thinking about audience. I was blogging to think, to process, to understand. To understand myself and the world around me. I wasn’t really aware of or interested in community building so I didn’t really participate in the broader practice. Blogging was about me. Until things changed.

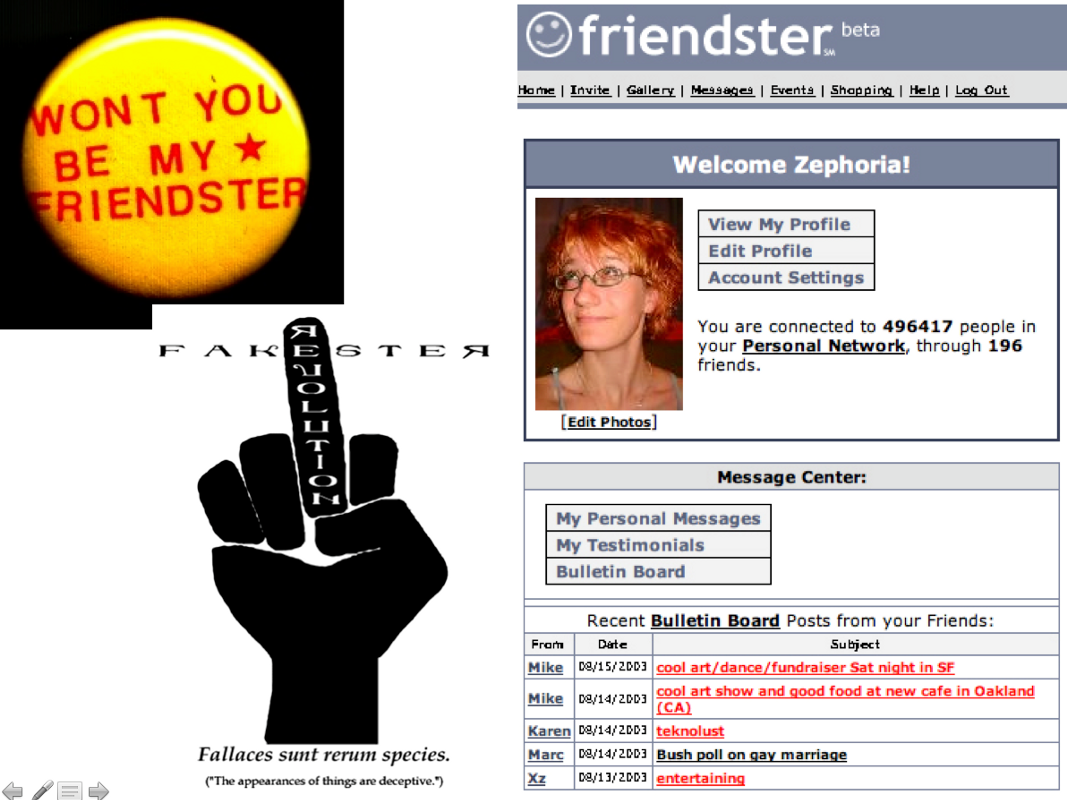

As research became more central to my life, my blog became more focused on my research. In December 2002, I started tracking Friendster. (Keep in mind that the first public news story was written about Friendster by the Village Voice in June of 2003.) I was documenting my understanding of the new technologies that were emerging because that’s what I was thinking about. But because I was writing about tech, my blog caught the eye of technology folks who were trying to track this new phenomenon.

As research became more central to my life, my blog became more focused on my research. In December 2002, I started tracking Friendster. (Keep in mind that the first public news story was written about Friendster by the Village Voice in June of 2003.) I was documenting my understanding of the new technologies that were emerging because that’s what I was thinking about. But because I was writing about tech, my blog caught the eye of technology folks who were trying to track this new phenomenon.

I became a blogger because people who identified as bloggers called me a blogger. And they linked to my blog. And commented on it. And talked about what I posted. I was invited to blog on group sites, like Many-to-Many, and participate in blogger-related activities. I became a part of the nascent blogging world, kinda by accident.

As I became understood as a blogger, people started asking me about my blogging practice. Errrr… Blogging practice? And then people started asking me about my monetization plans. Woah nelly! So I did some reflection and made a few very intentional decisions. I valued blogging because it allowed me to express what was on my mind without anyone else editing me, but I understood that I was becoming part of the public. I valued the freedom to have a single place where my voice sat, where I was in control, but I also had power. So I struggled, but I concluded that at the end of the day, I couldn’t keep this up if this stopped being about me. And so I decided to never add advertisements, to never commercialize my personal blog, and to never let others post there. I needed boundaries. I’d blog elsewhere under other terms, by my blog was mine.

I started thinking a lot more about blogging, both personally and professionally, when I went to work for Ev Williams at Blogger (already acquired by Google). My title was “ethnographic engineer.” (Gotta love Google titles.) And my job was to help the Blogger team better understand the diversity of practices unfolding in Blogger. I interviewed numerous bloggers. I randomly sampled Blogger entries to get a sense of the diversity of posts that we were seeing. And I helped the engineering team think about different types of practices. I also became much more involved in the blogging community, attending blogging events like Blogher ten years ago.

I made a decision to live certain parts of my life in public in order not to hide from myself, in order to be human in a networked age where I am more comfortable behind a keyboard than at a bar. But I also had to contend with the fact that I was visible in ways that were de-humanizing. As a public speaker, I am regularly objectified, just a mouthpiece on stage with no feelings. I’ve smiled my way through catcalls and sexualized commentary. Sadly, it hasn’t just been men who have objectified me. At the second Blogher, I was stunned to read many women blog about my talk by dissecting my hairstyle and clothing choices in condescending ways. I may have been a blogger, but I didn’t feel like it was a community. I felt like I had become another digital artifact to be poked and prodded.

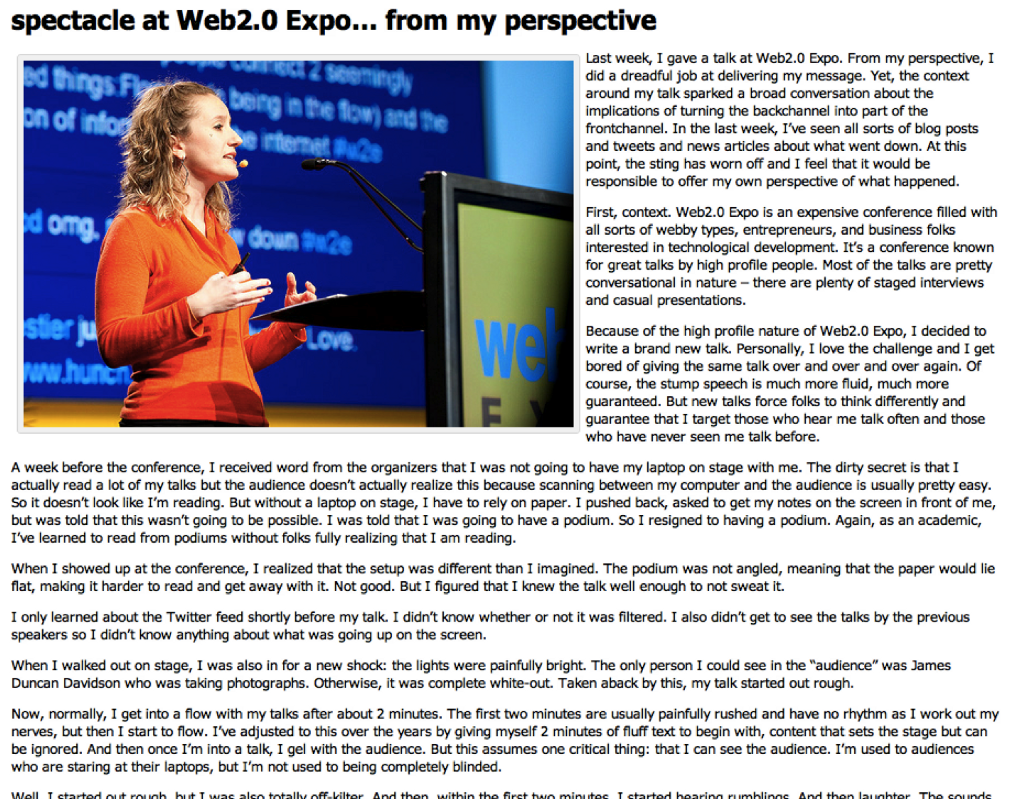

My experience with objectification took on a whole new level in 2009 when, at Web2.0 Expo, my experience on stage devolved. I wrote about this incident in gory detail on my blog, but the basic story is that I talk fast. And when I’m nervous, I talk even faster. I was nervous, it was a big stage, there were high-power lights so I couldn’t see anything. And there was a Twitter feed behind me that I couldn’t see. As I nervously started in on my talk, the audience began critiquing me on Twitter and then laughing at what others wrote. It devolved into outright misogyny—the Twitter stream was taken down and then put back up. The audience was loud but clearly not listening to what I had to say. I didn’t know what was going on, and I melted. I talked faster, I stared at the podium. I didn’t leave stage in tears, but I thought about doing so. It was humiliating.

My experience with objectification took on a whole new level in 2009 when, at Web2.0 Expo, my experience on stage devolved. I wrote about this incident in gory detail on my blog, but the basic story is that I talk fast. And when I’m nervous, I talk even faster. I was nervous, it was a big stage, there were high-power lights so I couldn’t see anything. And there was a Twitter feed behind me that I couldn’t see. As I nervously started in on my talk, the audience began critiquing me on Twitter and then laughing at what others wrote. It devolved into outright misogyny—the Twitter stream was taken down and then put back up. The audience was loud but clearly not listening to what I had to say. I didn’t know what was going on, and I melted. I talked faster, I stared at the podium. I didn’t leave stage in tears, but I thought about doing so. It was humiliating.

When I finally got off stage and online, I learned that people were talking about me as though I had no feelings. And so I decided to explain what it was like to be on that stage in that moment. It was gut-wrenching to write but it hit a chord. And it allowed me to see the beauty and pain of being public in every sense of the word. Being in public. Being a public figure. Being public with my feelings. Being public.

I’ve spent the last decade studying teenagers and their relationship to social media — in effect, their relationship to public life. Through the process, I’ve watched many of them struggle with what it means to be public, what it means to have a public voice — all in an environment where young people are not encouraged to be a part of public life. Over the last 30 years, we’ve systematically eliminated young people’s ability to participate in public life. They turn to technology as a relief valve, as an opportunity to have a space of their own. As a chance to be public. And, of course, we shoo them away from there too.

Because teens want to be *in* public, we assume that they want to *be* public. Thus, we assume that they don’t want privacy. Nothing could be further from the truth. Teens want to be a part of public life, but they want privacy from those who hold power over them. Having both is often very difficult so teenagers develop sophisticated techniques to be public and to have privacy. They focus more on hiding access to meaning than hiding access to content. They use the technologies they have around them to navigate their identity and voice. They are growing up in a digital world and they try to make sense of it the best they can. But all too often, they’re blamed and shamed for what they do and adults don’t take the time to understand where they’re coming from and why.

In spending a decade with youth, I’ve learned a lot about what it means to be public. I’ve learned how to encode what I’m saying, layer my messages to reveal different things to different people. I’ve learned how to appear to be open and still keep some things to myself. I’ve learned how to use different tools for different parts of my network. And I’ve learned just how significantly the internet has changed since I was a teen.

I grew up in an era when the internet was comprised of self-identified geeks, freaks, and queers. Claiming all three, I felt quite at home. Today’s internet is mainstream. Today’s youth are growing up in a world where technology is taken for granted. Traditional aspects of power are asserted through technology. It’s no longer the realm of the marginalized, but the new mechanisms by which marginalization happen.

A decade ago, people talked about the democratizing power of blogging, but even back then we all realized that some voices were more visible than others. This is what sparked the creation of Blogher in the first place. Women’s voices were often ignored online, even when they were participating. The mechanisms of structural inequality got reified, which went against what many people imagined the internet to be about. The conversation focused on how we could create a future based on common values, a future that challenged the status quo. We never imagined we would be the status quo.

As more and more people have embraced social media and blogging, normative societal values have dominated our cultural frames about these tools. It’s no longer about imagined communities, new mechanisms of enlightenment, or resisting institutional power. Technology is situated within a context of capitalism, traditional politics, and geoglobal power struggles.

With that in mind, what does it mean to be a blogger today? What does it mean to be public? Is value only derived by commercial acts of self-branding? How can we understand the work of identity and public culture development? Is there a coherent sense of being a blogger? What are the shared values that underpin the practice?

I started blogging to feel my humanity. I became a part of the blogging community to participate in shaping a society that I care about. I reflect and share publicly to engage others and build understanding. This is my blogging practice. What is yours?

(This post was originally posted on August 6, 2014 in The Message on Medium.)