Lots of folks are unaware that multiple brands are owned by the same company (e.g., the same company owns Gap, Banana Republic, Old Navy). Consumer activists often complain that this practice is deceptive because it tricks consumers into believing that there are big distinctions between brands when, often, the differences are minimal. Personally, while I’d love to see more consumer brand awareness, but I think that brand distinctions play an important role. I just wish that the tech industry would figure this out.

Lots of folks are unaware that multiple brands are owned by the same company (e.g., the same company owns Gap, Banana Republic, Old Navy). Consumer activists often complain that this practice is deceptive because it tricks consumers into believing that there are big distinctions between brands when, often, the differences are minimal. Personally, while I’d love to see more consumer brand awareness, but I think that brand distinctions play an important role. I just wish that the tech industry would figure this out.

I’m a relatively educated consumer and I’m also one of the most brand-loyal customers out there. When it comes to food and personal care products, many of my brand decisions come down to smell and taste, even when these are completely manufactured in a lab in New Jersey to differentiate soaps, toothpastes, and other products that are chemically identical. I buy All laundry detergent and not other Unilever brands (Surf, Wisk) or P&G brands (Tide, Gain, Cheer) simply because it smells better. When it comes to clothes, fit trumps everything.

In other words, my purchasing decisions are heavily affected by “interface.” (Politics and convenience too…) When a company changes the interface, I get cranky. I’m still cranky with my favorite pretzel brand for eliminating the air bubbles in their pretzels that allowed for more salt to build up. The reason that I’m committed to most consumer brands is not because I love the company. For many products, I’m not even influenced by the lifestyle being sold. I simply love the interface. Luckily, most retail companies get that their interface matters and when they futz with it, they create a separate brand or segment the primary brand into “Original” and “New with XYZ.” In the world of retail, a brand represents its interface. There are interfaces I like, those that I don’t, and those that I’m completely ambivalent about. But the interface often matters a whole lot more than the “features.”

Why do technology companies often fail to understand branding the way retail folks do? Many think that they can change the interface at whim to spice-up their product. They approach user retention as user lock-in, rather than user satisfaction and commitment. They try to shove everyone into the same interface in a one-size-fits-all paradigm that tends to fit few. Why??

Unfortunately, I don’t think that many companies are aware of the limitations of their brands. When they’re flying high, their brands are invincible and extending it to a wide array of products seems natural. Yet, over time, tech companies’ brands get entrenched. Certain users identify with it; others don’t. New products using that brand enter into the market with both cachet and baggage. Yet, tech companies tend to hold onto their brands for dear life and assume users will forget. Foolish.

We all know that youth talk about certain products as “sooo last year.” This tends to cover a genre rather than a brand. Yet, teens also have plenty to say about the brands themselves. Yahoo! and AOL, for example, are for old people. When I asked why they use Yahoo! Mail and AOL Instant Messaging if they’re for old people, they responded by telling me that their parents made those accounts for them. Furthermore, email is for communicating with old people and AIM is “so middle school” and both are losing ground to SNS and SMS. While Microsoft is viewed in equally lame light amongst youth I spoke with, it’s at least valued as a brand for doing work. Yet, even youth who use MSN messenger think that msn.com is for old people. Why shouldn’t they? When I logged in just now, the main visual was a woman with white hair sitting on a hospital bed with the caption “10 Vital Questions to Ask Your Doctor.”

Take a look at all of the major portals attempting to reach universal audiences. Now imagine yourself as a teen. Why would you even visit them? Even if you were the rare teen who cared about Autos, Careers & Jobs, Dating & Personals, Finance & Money, Health & Fitness, or Real Estate, one click in and you know that this content is not targeted at you. Even the sites that allow you to “personalize” your modules rarely let you get rid of these or make them relevant to you. To make matters worse, now that these companies are heading towards mobile, they are taking these one-size-fits-all interfaces and cluttering up the phones. Ugg! Why?

I would like to offer two bits of advice to all of the major tech companies out there: 1) Start sub-branding; and 2) Start doing real personalization.

If you’re creating a new product, launch it with a new brand. Put your flagship brand on the bottom of the page, letting people know that this is backed by you – this is not about deception. Advertise it alongside your flagship brand if you think that’ll gain you traction. But let the new product develop a life of its own and not get flattened by a universal brand. Some products should be niche, especially those targeted at youth; while youth are happy to use well-established tools, they also like to distinguish their practices from those of adults and mature into new brands. In other words, they aren’t going to fall to your lock-in for very long. If you’re buying a well-established brand, don’t flatten it, especially if it’s loved by youth. Kudos to Google wrt YouTube; boo to Yahoo! wrt Launch. Even at the coarse demographic level, people are different; don’t treat them as a universal bunch, even if your back-end serves up the same thing to different interfaces.

Personalization is more than skinning and moving modules around. Give me a blank slate and let me add modules that might be relevant to me. Alternatively, make some good initial guesses based on what you know about me and let me modify them from the getgo. Help me find the modules that are most likely to appeal to me – you already have a lot of data on what it is that I do; use it for something that helps me. This is particularly important if there are going to be a bazillion Apps or Gadgets or Widgets out there because I don’t want to comb through the crud. A targeted interface is just as important as a targeted ad.

Above all, understand that no brand is universally loved and one size does not fit all. Most of us look like idiots in XXL shirts and we don’t want our technology interfaces to be XXL. People like brands that fit them like a glove. The tech industry serves up ads this way; why doesn’t it get this when it comes to their own brand? Technology is well positioned to create sub-brands and personalize those brands from there. It’s high time for the tech industry to grow up and start doing so.

Last fall, Hiyam Hijazi-Omari and Rivka Ribak presented a paper called “Playing With Fire: On the domestication of the mobile phone among Palestinian teenage girls in Israel” at AOIR. They studied teen girls who received their mobile phones from their boyfriends and hid them from everyone else. Through this lens, they examine how the mobile phone alters social dynamics, relationships, and the construction of gender in Palestine. In short, they document how culturally specific gendered practices (not technological features) frame the meaning and value of technology.

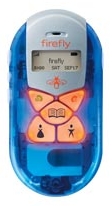

Faux electronics for children have been around for a while, especially in the world of mobile phones. Lately, though, technology has become cheaper and what was once faux is now real. While children’s laptops are still more hype than reality, phones for children are appearing all over the place. These “kiddie” phones are often smaller, simpler, and more brightly colored.

Faux electronics for children have been around for a while, especially in the world of mobile phones. Lately, though, technology has become cheaper and what was once faux is now real. While children’s laptops are still more hype than reality, phones for children are appearing all over the place. These “kiddie” phones are often smaller, simpler, and more brightly colored. Kenyan phone users do not have monthly phone plans; they pay for prepaid credits (like most of the world). Prior to the election, getting credits was easy – they were available in kiosks, stores, bars, anywhere you could imagine. Yet, these venues all closed shop after the election because of the violence and looting. Credits have become a rare commodity and the price has skyrocketed. Credits have also turned into a currency and people are trading credits for food and medicine. Credits are worth more than the government’s currency. Because of difficulties in getting credits to citizens, a service called

Kenyan phone users do not have monthly phone plans; they pay for prepaid credits (like most of the world). Prior to the election, getting credits was easy – they were available in kiosks, stores, bars, anywhere you could imagine. Yet, these venues all closed shop after the election because of the violence and looting. Credits have become a rare commodity and the price has skyrocketed. Credits have also turned into a currency and people are trading credits for food and medicine. Credits are worth more than the government’s currency. Because of difficulties in getting credits to citizens, a service called