I’m intrigued by the reaction that has unfolded around the Facebook “emotion contagion” study. (If you aren’t familiar with this, read this primer.) As others have pointed out, the practice of A/B testing content is quite common. And Facebook has a long history of experimenting on how it can influence people’s attitudes and practices, even in the realm of research. An earlier study showed that Facebook decisions could shape voters’ practices. But why is it that *this* study has sparked a firestorm?

In asking people about this, I’ve been given two dominant reasons:

- People’s emotional well-being is sacred.

- Research is different than marketing practices.

I don’t find either of these responses satisfying.

The Consequences of Facebook’s Experiment

Facebook’s research team is not truly independent of product. They have a license to do research and publish it, provided that it contributes to the positive development of the company. If Facebook knew that this research would spark the negative PR backlash, they never would’ve allowed it to go forward or be published. I can only imagine the ugliness of the fight inside the company now, but I’m confident that PR is demanding silence from researchers.

I do believe that the research was intended to be helpful to Facebook. So what was the intended positive contribution of this study? I get the sense from Adam Kramer’s comments that the goal was to determine if content sentiment could affect people’s emotional response after being on Facebook. In other words, given that Facebook wants to keep people on Facebook, if people came away from Facebook feeling sadder, presumably they’d not want to come back to Facebook again. Thus, it’s in Facebook’s better interest to leave people feeling happier. And this study suggests that the sentiment of the content influences this. This suggests that one applied take-away for product is to downplay negative content. Presumably this is better for users and better for Facebook.

We can debate all day long as to whether or not this is what that study actually shows, but let’s work with this for a second. Let’s say that pre-study Facebook showed 1 negative post for every 3 positive and now, because of this study, Facebook shows 1 negative post for every 10 positive ones. If that’s the case, was the one week treatment worth the outcome for longer term content exposure? Who gets to make that decision?

Folks keep talking about all of the potential harm that could’ve happened by the study – the possibility of suicides, the mental health consequences. But what about the potential harm of negative content on Facebook more generally? Even if we believe that there were subtle negative costs to those who received the treatment, the ongoing costs of negative content on Facebook every week other than that 1 week experiment must be more costly. How then do we account for positive benefits to users if Facebook increased positive treatments en masse as a result of this study? Of course, the problem is that Facebook is a black box. We don’t know what they did with this study. The only thing we know is what is published in PNAS and that ain’t much.

Of course, if Facebook did make the content that users see more positive, should we simply be happy? What would it mean that you’re more likely to see announcements from your friends when they are celebrating a new child or a fun night on the town, but less likely to see their posts when they’re offering depressive missives or angsting over a relationship in shambles? If Alice is happier when she is oblivious to Bob’s pain because Facebook chooses to keep that from her, are we willing to sacrifice Bob’s need for support and validation? This is a hard ethical choice at the crux of any decision of what content to show when you’re making choices. And the reality is that Facebook is making these choices every day without oversight, transparency, or informed consent.

Algorithmic Manipulation of Attention and Emotions

Facebook actively alters the content you see. Most people focus on the practice of marketing, but most of what Facebook’s algorithms do involve curating content to provide you with what they think you want to see. Facebook algorithmically determines which of your friends’ posts you see. They don’t do this for marketing reasons. They do this because they want you to want to come back to the site day after day. They want you to be happy. They don’t want you to be overwhelmed. Their everyday algorithms are meant to manipulate your emotions. What factors go into this? We don’t know.

Facebook is not alone in algorithmically predicting what content you wish to see. Any recommendation system or curatorial system is prioritizing some content over others. But let’s compare what we glean from this study with standard practice. Most sites, from major news media to social media, have some algorithm that shows you the content that people click on the most. This is what drives media entities to produce listicals, flashy headlines, and car crash news stories. What do you think garners more traffic – a detailed analysis of what’s happening in Syria or 29 pictures of the cutest members of the animal kingdom? Part of what media learned long ago is that fear and salacious gossip sell papers. 4chan taught us that grotesque imagery and cute kittens work too. What this means online is that stories about child abductions, dangerous islands filled with snakes, and celebrity sex tape scandals are often the most clicked on, retweeted, favorited, etc. So an entire industry has emerged to produce crappy click bait content under the banner of “news.”

Guess what? When people are surrounded by fear-mongering news media, they get anxious. They fear the wrong things. Moral panics emerge. And yet, we as a society believe that it’s totally acceptable for news media – and its click bait brethren – to manipulate people’s emotions through the headlines they produce and the content they cover. And we generally accept that algorithmic curators are perfectly well within their right to prioritize that heavily clicked content over others, regardless of the psychological toll on individuals or the society. What makes their practice different? (Other than the fact that the media wouldn’t hold itself accountable for its own manipulative practices…)

Somehow, shrugging our shoulders and saying that we promoted content because it was popular is acceptable because those actors don’t voice that their intention is to manipulate your emotions so that you keep viewing their reporting and advertisements. And it’s also acceptable to manipulate people for advertising because that’s just business. But when researchers admit that they’re trying to learn if they can manipulate people’s emotions, they’re shunned. What this suggests is that the practice is acceptable, but admitting the intention and being transparent about the process is not.

But Research is Different!!

As this debate has unfolded, whenever people point out that these business practices are commonplace, folks respond by highlighting that research or science is different. What unfolds is a high-browed notion about the purity of research and its exclusive claims on ethical standards.

Do I think that we need to have a serious conversation about informed consent? Absolutely. Do I think that we need to have a serious conversation about the ethical decisions companies make with user data? Absolutely. But I do not believe that this conversation should ever apply just to that which is categorized under “research.” Nor do I believe that academe is necessarily providing a golden standard.

Academe has many problems that need to be accounted for. Researchers are incentivized to figure out how to get through IRBs rather than to think critically and collectively about the ethics of their research protocols. IRBs are incentivized to protect the university rather than truly work out an ethical framework for these issues. Journals relish corporate datasets even when replicability is impossible. And for that matter, even in a post-paper era, journals have ridiculous word count limits that demotivate researchers from spelling out all of the gory details of their methods. But there are also broader structural issues. Academe is so stupidly competitive and peer review is so much of a game that researchers have little incentive to share their studies-in-progress with their peers for true feedback and critique. And the status games of academe reward those who get access to private coffers of data while prompting those who don’t to chastise those who do. And there’s generally no incentive for corporates to play nice with researchers unless it helps their prestige, hiring opportunities, or product.

IRBs are an abysmal mechanism for actually accounting for ethics in research. By and large, they’re structured to make certain that the university will not be liable. Ethics aren’t a checklist. Nor are they a universal. Navigating ethics involves a process of working through the benefits and costs of a research act and making a conscientious decision about how to move forward. Reasonable people differ on what they think is ethical. And disciplines have different standards for how to navigate ethics. But we’ve trained an entire generation of scholars that ethics equals “that which gets past the IRB” which is a travesty. We need researchers to systematically think about how their practices alter the world in ways that benefit and harm people. We need ethics to not just be tacked on, but to be an integral part of how *everyone* thinks about what they study, build, and do.

There’s a lot of research that has serious consequences on the people who are part of the study. I think about the work that some of my colleagues do with child victims of sexual abuse. Getting children to talk about these awful experiences can be quite psychologically tolling. Yet, better understanding what they experienced has huge benefits for society. So we make our trade-offs and we do research that can have consequences. But what warms my heart is how my colleagues work hard to help those children by providing counseling immediately following the interview (and, in some cases, follow-up counseling). They think long and hard about each question they ask, and how they go about asking it. And yet most IRBs wouldn’t let them do this work because no university wants to touch anything that involves kids and sexual abuse. Doing research involves trade-offs and finding an ethical path forward requires effort and risk.

It’s far too easy to say “informed consent” and then not take responsibility for the costs of the research process, just as it’s far too easy to point to an IRB as proof of ethical thought. For any study that involves manipulation – common in economics, psychology, and other social science disciplines – people are only so informed about what they’re getting themselves into. You may think that you know what you’re consenting to, but do you? And then there are studies like discrimination audit studies in which we purposefully don’t inform people that they’re part of a study. So what are the right trade-offs? When is it OK to eschew consent altogether? What does it mean to truly be informed? When it being informed not enough? These aren’t easy questions and there aren’t easy answers.

I’m not necessarily saying that Facebook made the right trade-offs with this study, but I think that the scholarly reaction of research is only acceptable with IRB plus informed consent is disingenuous. Of course, a huge part of what’s at stake has to do with the fact that what counts as a contract legally is not the same as consent. Most people haven’t consented to all of Facebook’s terms of service. They’ve agreed to a contract because they feel as though they have no other choice. And this really upsets people.

A Different Theory

The more I read people’s reactions to this study, the more that I’ve started to think that the outrage has nothing to do with the study at all. There is a growing amount of negative sentiment towards Facebook and other companies that collect and use data about people. In short, there’s anger at the practice of big data. This paper provided ammunition for people’s anger because it’s so hard to talk about harm in the abstract.

For better or worse, people imagine that Facebook is offered by a benevolent dictator, that the site is there to enable people to better connect with others. In some senses, this is true. But Facebook is also a company. And a public company for that matter. It has to find ways to become more profitable with each passing quarter. This means that it designs its algorithms not just to market to you directly but to convince you to keep coming back over and over again. People have an abstract notion of how that operates, but they don’t really know, or even want to know. They just want the hot dog to taste good. Whether it’s couched as research or operations, people don’t want to think that they’re being manipulated. So when they find out what soylent green is made of, they’re outraged. This study isn’t really what’s at stake. What’s at stake is the underlying dynamic of how Facebook runs its business, operates its system, and makes decisions that have nothing to do with how its users want Facebook to operate. It’s not about research. It’s a question of power.

I get the anger. I personally loathe Facebook and I have for a long time, even as I appreciate and study its importance in people’s lives. But on a personal level, I hate the fact that Facebook thinks it’s better than me at deciding which of my friends’ posts I should see. I hate that I have no meaningful mechanism of control on the site. And I am painfully aware of how my sporadic use of the site has confused their algorithms so much that what I see in my newsfeed is complete garbage. And I resent the fact that because I barely use the site, the only way that I could actually get a message out to friends is to pay to have it posted. My minimal use has made me an algorithmic pariah and if I weren’t technologically savvy enough to know better, I would feel as though I’ve been shunned by my friends rather than simply deemed unworthy by an algorithm. I also refuse to play the game to make myself look good before the altar of the algorithm. And every time I’m forced to deal with Facebook, I can’t help but resent its manipulations.

There’s also a lot that I dislike about the company and its practices. At the same time, I’m glad that they’ve started working with researchers and started publishing their findings. I think that we need more transparency in the algorithmic work done by these kinds of systems and their willingness to publish has been one of the few ways that we’ve gleaned insight into what’s going on. Of course, I also suspect that the angry reaction from this study will prompt them to clamp down on allowing researchers to be remotely public. My gut says that they will naively respond to this situation as though the practice of research is what makes them vulnerable rather than their practices as a company as a whole. Beyond what this means for researchers, I’m concerned about what increased silence will mean for a public who has no clue of what’s being done with their data, who will think that no new report of terrible misdeeds means that Facebook has stopped manipulating data.

Information companies aren’t the same as pharmaceuticals. They don’t need to do clinical trials before they put a product on the market. They can psychologically manipulate their users all they want without being remotely public about exactly what they’re doing. And as the public, we can only guess what the black box is doing.

There’s a lot that needs reformed here. We need to figure out how to have a meaningful conversation about corporate ethics, regardless of whether it’s couched as research or not. But it’s not so simple as saying that a lack of a corporate IRB or a lack of a golden standard “informed consent” means that a practice is unethical. Almost all manipulations that take place by these companies occur without either one of these. And they go unchecked because they aren’t published or public.

Ethical oversight isn’t easy and I don’t have a quick and dirty solution to how it should be implemented. But I do have a few ideas. For starters, I’d like to see any company that manipulates user data create an ethics board. Not an IRB that approves research studies, but an ethics board that has visibility into all proprietary algorithms that could affect users. For public companies, this could be done through the ethics committee of the Board of Directors. But rather than simply consisting of board members, I think that it should consist of scholars and users. I also think that there needs to be a mechanism for whistleblowing regarding ethics from within companies because I’ve found that many employees of companies like Facebook are quite concerned by certain algorithmic decisions, but feel as though there’s no path to responsibly report concerns without going fully public. This wouldn’t solve all of the problems, nor am I convinced that most companies would do so voluntarily, but it is certainly something to consider. More than anything, I want to see users have the ability to meaningfully influence what’s being done with their data and I’d love to see a way for their voices to be represented in these processes.

I’m glad that this study has prompted an intense debate among scholars and the public, but I fear that it’s turned into a simplistic attack on Facebook over this particular study rather than a nuanced debate over how we create meaningful ethical oversight in research and practice. The lines between research and practice are always blurred and information companies like Facebook make this increasingly salient. No one benefits by drawing lines in the sand. We need to address the problem more holistically. And, in the meantime, we need to hold companies accountable for how they manipulate people across the board, regardless of whether or not it’s couched as research. If we focus too much on this study, we’ll lose track of the broader issues at stake.

What is “fairness”? And what happens when technology decides?

What is “fairness”? And what happens when technology decides?

Technology is changing work. It’s changing labor. Some imagine radical transformations, both positive and negatives. Words like robots and drones conjure up all sorts of science fiction imagination. But many of the transformations that are underway are far more mundane and, yet, phenomenally disruptive, especially for those who are struggling to figure out their place in this new ecosystem. Disruption, a term of endearment in the tech industry, sends shutters down the spine of many, from those whose privilege exists because of the status quo to those who are struggling to put bread on the table.

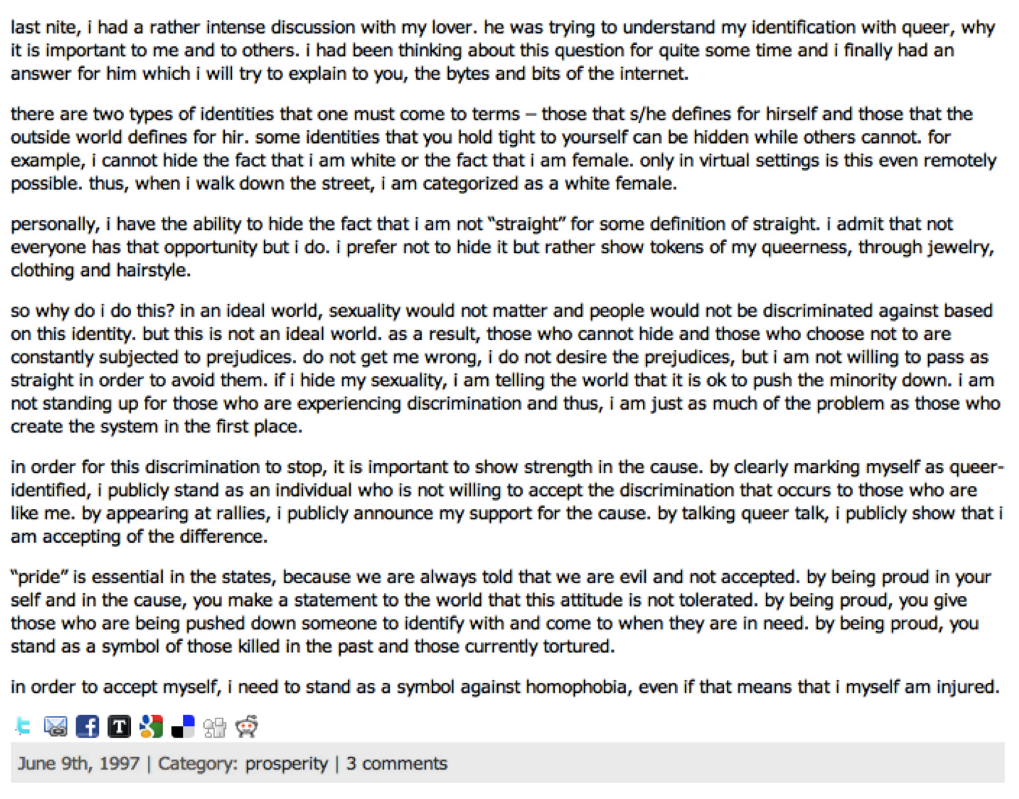

Technology is changing work. It’s changing labor. Some imagine radical transformations, both positive and negatives. Words like robots and drones conjure up all sorts of science fiction imagination. But many of the transformations that are underway are far more mundane and, yet, phenomenally disruptive, especially for those who are struggling to figure out their place in this new ecosystem. Disruption, a term of endearment in the tech industry, sends shutters down the spine of many, from those whose privilege exists because of the status quo to those who are struggling to put bread on the table. I started blogging in 1997. I was 19 years old. I didn’t call it blogging then, and my blog didn’t look like it does now. It was a manually-created HTML site with a calendar made of tables (OMG tables) and Geocities-style forward and back buttons with terrible graphics. I posted entries a few times a week as part of an independent study on Buddhism as a Brown University student that involved both meditation and self-reflection. Each week, the monk I was working with would ask me to reflect on certain things, and I would write. And write. And write. He lived in Ohio and had originally proposed sending letters, but I thought pencils were a foreign concept. I decided to type my thoughts and that, if I was going to type them, I might as well put them up online. Ah, teen logic.

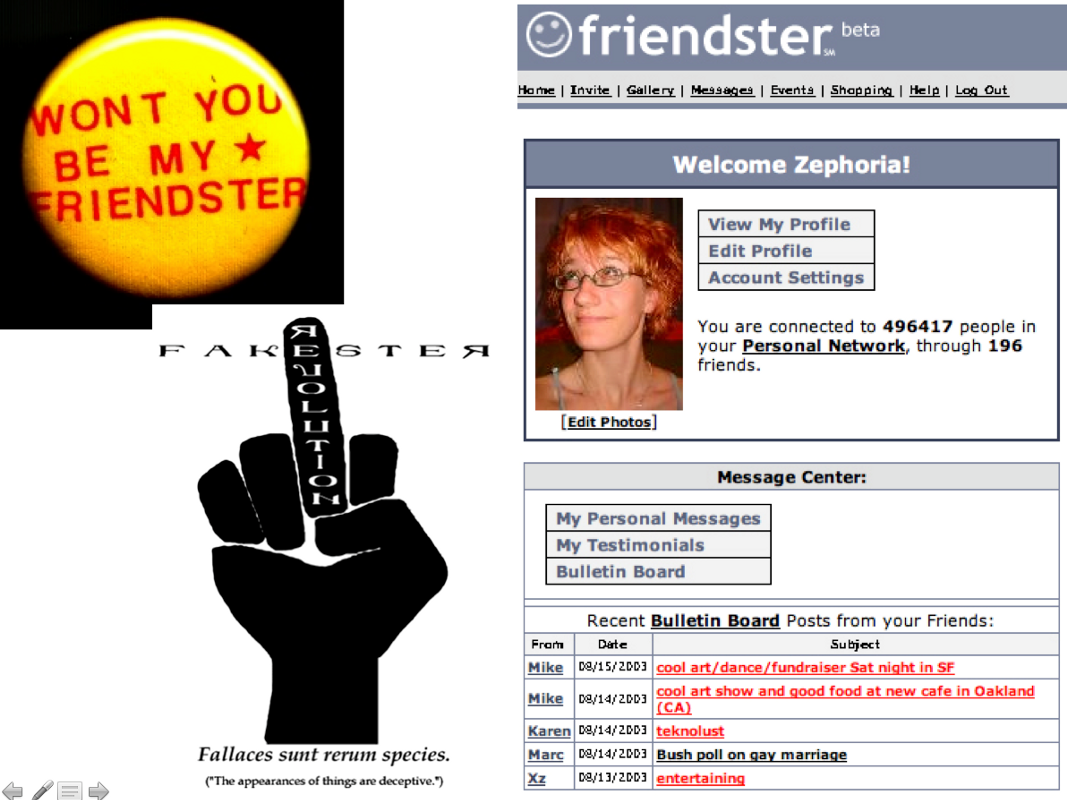

I started blogging in 1997. I was 19 years old. I didn’t call it blogging then, and my blog didn’t look like it does now. It was a manually-created HTML site with a calendar made of tables (OMG tables) and Geocities-style forward and back buttons with terrible graphics. I posted entries a few times a week as part of an independent study on Buddhism as a Brown University student that involved both meditation and self-reflection. Each week, the monk I was working with would ask me to reflect on certain things, and I would write. And write. And write. He lived in Ohio and had originally proposed sending letters, but I thought pencils were a foreign concept. I decided to type my thoughts and that, if I was going to type them, I might as well put them up online. Ah, teen logic. As research became more central to my life, my blog became more focused on my research. In December 2002, I started tracking Friendster. (Keep in mind that the first public news story was written about Friendster by the

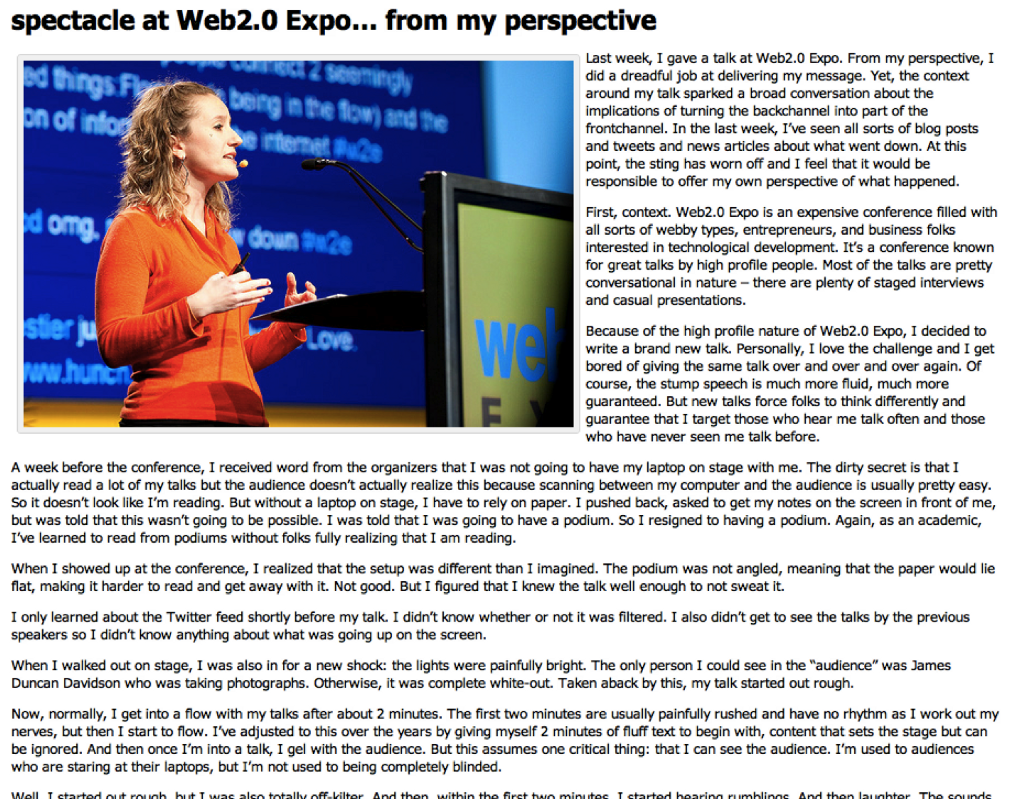

As research became more central to my life, my blog became more focused on my research. In December 2002, I started tracking Friendster. (Keep in mind that the first public news story was written about Friendster by the  My experience with objectification took on a whole new level in 2009 when, at Web2.0 Expo, my experience on stage devolved.

My experience with objectification took on a whole new level in 2009 when, at Web2.0 Expo, my experience on stage devolved.

Over the last few years, I’ve been working with an amazing collection of researchers in an effort to better understand technology’s relationship to human trafficking and, more specifically, the commercial sexual exploitation of children. In the process, I’ve learned a lot about the politics of sex work and the political framing of sex trafficking. What’s been infuriating is to watch the way in which journalists and the public reify a Hollywood narrative of what trafficking is supposed to look like

Over the last few years, I’ve been working with an amazing collection of researchers in an effort to better understand technology’s relationship to human trafficking and, more specifically, the commercial sexual exploitation of children. In the process, I’ve learned a lot about the politics of sex work and the political framing of sex trafficking. What’s been infuriating is to watch the way in which journalists and the public reify a Hollywood narrative of what trafficking is supposed to look like