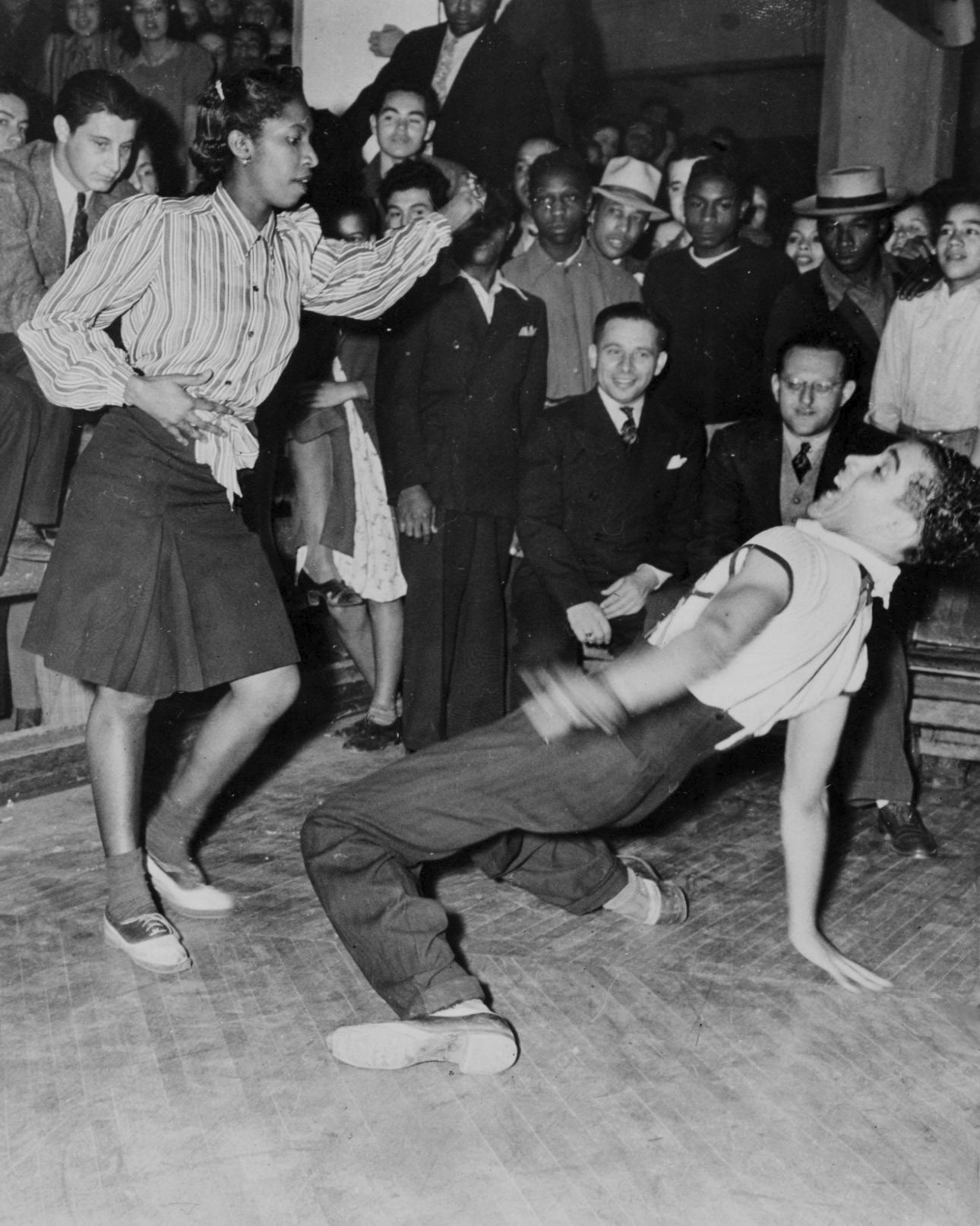

Close your eyes and imagine what it was like to be a teenager in the 1920s. Perhaps you are out late dancing swing to jazz or dressed up as a flapper. Most likely, you don’t visualize yourself stuck at home unable to see your friends like today’s teenagers. And for good reason. In the 1920s, teenagers used to complain when their parents made them come home before 11pm. Many, in fact, earned their own money; compulsory high school wasn’t fully implemented until the 1930s when adult labor became anxious about the limited number of available jobs.

Close your eyes and imagine what it was like to be a teenager in the 1920s. Perhaps you are out late dancing swing to jazz or dressed up as a flapper. Most likely, you don’t visualize yourself stuck at home unable to see your friends like today’s teenagers. And for good reason. In the 1920s, teenagers used to complain when their parents made them come home before 11pm. Many, in fact, earned their own money; compulsory high school wasn’t fully implemented until the 1930s when adult labor became anxious about the limited number of available jobs.

Although contemporary parents fret incessantly about teenagers, most people don’t realize that the very concept of a “teenager” is a 1940s marketing invention. And it didn’t arrive overnight. It started with a transformation in the 1890s when activists began to question child labor and the psychologist G. Stanley Hall identified a state of “adolescence” that was used to propel significant changes in labor laws. By the early 1900s, with youth out of the work force and having far too much free time, concerns about the safety and morality of the young emerged, prompting reformers to imagine ways to put youthful energy to good use. Up popped the Scouts, a social movement intended to help produce robust youth, fit in body, mind, and soul. This inadvertently became a training ground for World War I soldiers who, by the 1920s, were ready to let loose. And then along came the Great Depression, sending a generation into a tailspin and prompting government intervention. While the US turned to compulsory high school and the Civilian Conservation Corps, Germany saw the rise of Hitler Youth. And an entire cohort, passionate about being a part of a community with meaning, was mobilized on the march towards World War II.

All of this (and much more) is brilliantly documented in Jon Savage’s beautiful historical account Teenage: The Creation of Youth Culture. This book helped me rethink how teenagers are currently understood in light of how they were historically positioned. Adolescence is one of many psychological and physical transformations that people go through as they mature, but being a teenager is purely a social construct, laden with all sorts of political and economic interests.

When I heard that Savage’s book was being turned into a film, I was both ecstatic and doubtful. How could a filmmaker do justice to the 576 pages of historical documentation? To my surprise and delight, the answer was simple: make a film that brings to visual life the historical texts that Savage referenced.

In his new documentary, Teenage, Matt Wolf weaves together an unbelievable collection of archival footage to produce a breathless visual collage. Overlaid on top of this visual eye candy are historical notes and diary entries that bring to life the voices and experiences of teens in the first half of the 20th century. Although this film invites the viewer to reflect on the past, doing so forces a reflection on the present. I can’t help but wonder: what will historians think of our contemporary efforts to isolate young people “for their own good”?

This film is making its way through US independent theaters so it may take a while until you can see it, but to whet your appetite, watch the trailer:

(This entry was first posted on April 25, 2014 at Medium under the title “A Dazzling Film About Youth in the Early 20th Century” as part of The Message.)