For months I have been concerned about how what I was seeing on the ground and in various networks was not at all aligned with what pundits were saying. I knew the polling infrastructure had broken, but whenever I told people about the problems with the sampling structure, they looked at me like an alien and told me to stop worrying. Over the last week, I started to accept that I was wrong. I wasn’t.

And I blame the media.

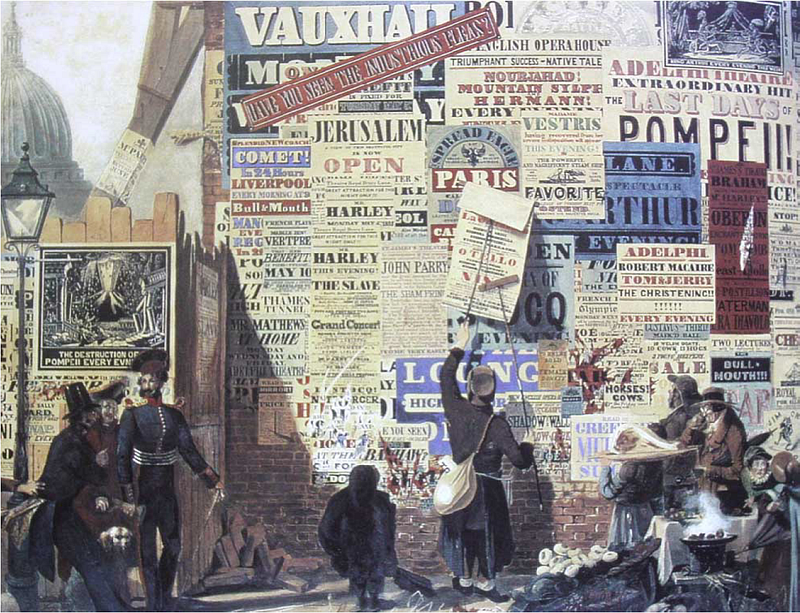

The media is supposed to be a check to power, but, for years now, it has basked in becoming power in its own right. What worries me right now is that, as it continues to report out the spectacle, it has no structure for self-reflection, for understanding its weaknesses, its potential for manipulation.

The media is supposed to be a check to power, but, for years now, it has basked in becoming power in its own right. What worries me right now is that, as it continues to report out the spectacle, it has no structure for self-reflection, for understanding its weaknesses, its potential for manipulation.

I believe in data, but data itself has become spectacle. I cannot believe that it has become acceptable for media entities to throw around polling data without any critique of the limits of that data, to produce fancy visualizations which suggest that numbers are magical information. Every pollster got it wrong. And there’s a reason. They weren’t paying attention to the various structural forces that made their sample flawed, the various reasons why a disgusted nation wasn’t going to contribute useful information to inform a media spectacle. This abuse of data has to stop. We need data to be responsible, not entertainment.

This election has been a spectacle because the media has enjoyed making it as such. And in doing so, they showcased just how easily they could be gamed. I refer to the sector as a whole because individual journalists and editors are operating within a structural frame, unmotivated to change the status quo even as they see similar structural problems to the ones I do. They feel as though they “have” to tell a story because others are doing so, because their readers can’t resist reading. They live in the world pressured by clicks and other elements of the attention economy. They need attention in order to survive financially. And they need a spectacle, a close race.

We all know that story. It’s not new. What is new is that they got played.

Over the last year, I’ve watched as a wide variety of decentralized pro-Trump actors first focused on getting the media to play into his candidacy as spectacle, feeding their desire for a show. In the last four months, I watched those same networks focus on depressing turnout, using the media to trigger the populace to feel so disgusted and frustrated as to disengage. It really wasn’t hard because the media was so easy to mess with. And they were more than happy to spend a ridiculous amount of digital ink circling round and round into a frenzy.

Around the world, people have been looking at us in a state of confusion and shock, unsure how we turned our democracy into a new media spectacle. What hath 24/7 news, reality TV, and social media wrought? They were right to ask. We were irresponsible to ignore.

In the tech sector, we imagined that decentralized networks would bring people together for a healthier democracy. We hung onto this belief even as we saw that this wasn’t playing out. We built the structures for hate to flow along the same pathways as knowledge, but we kept hoping that this wasn’t really what was happening. We aided and abetted the media’s suicide.

The red pill is here. And it ain’t pretty.

We live in a world shaped by fear and hype, not because it has to be that way, but because this is the obvious paradigm that can fuel the capitalist information architectures we have produced.

Many critics think that the answer is to tear down capitalism, make communal information systems, or get rid of social media. I disagree. But I do think that we need to actively work to understand complexity, respectfully engage people where they’re at, and build the infrastructure to enable people to hear and appreciate different perspectives. This is what it means to be truly informed.

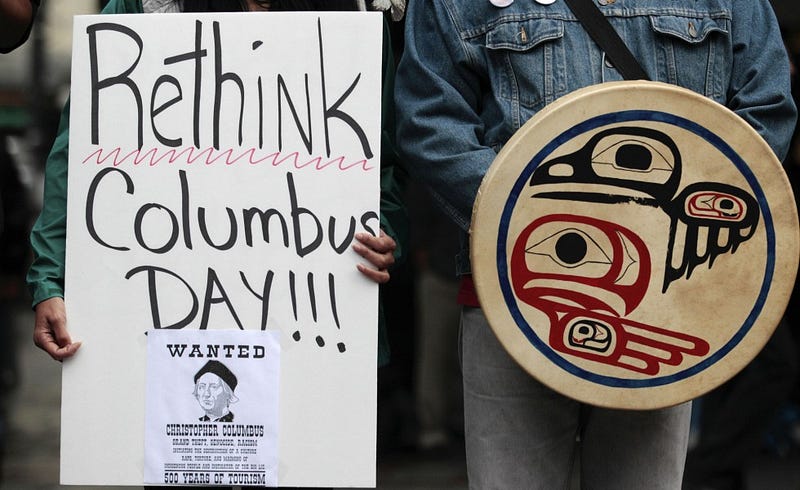

There are many reasons why we’ve fragmented as a country. From the privatization of the military (which undermined the development of diverse social networks) to our information architectures, we live in a moment where people do not know how to hear or understand one another. And our obsession with quantitative data means that we think we understand when we hear numbers in polls, which we use to judge people whose views are different than our own. This is not productive.

Most people are not apathetic, but they are disgusted and exhausted. We have unprecedented levels of anxiety and fear in our country. The feelings of insecurity and inequality cannot be written off by economists who want to say that the world is better today than it ever was. It doesn’t feel that way. And it doesn’t feel that way because, all around us, the story is one of disenfranchisement, difference, and uncertainty.

All of us who work in the production and dissemination of information need to engage in a serious reality check.

The media industry needs to take responsibility for its role in producing spectacle for selfish purposes. There is a reason that the public doesn’t trust institutions in this country. And what the media has chosen to do is far from producing information. It has chosen to produce anxiety in the hopes that we will obsessively come back for more. That is unhealthy. And it’s making us an unhealthy country.

Spectacle has a cost. It always has. And we are about to see what that cost will be.

(This was first posted at Points.)

At what age should children be allowed to access the internet without parental oversight? This is a hairy question that raises all sorts of issues about rights, freedoms, morality, skills, and cognitive capability. Cultural values also come into play full force on this one.

At what age should children be allowed to access the internet without parental oversight? This is a hairy question that raises all sorts of issues about rights, freedoms, morality, skills, and cognitive capability. Cultural values also come into play full force on this one.